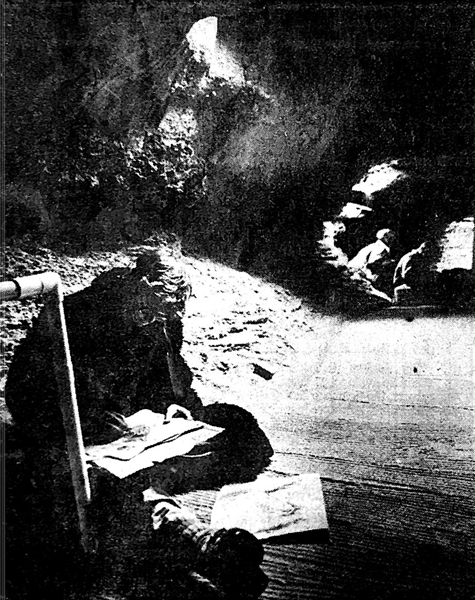

A Cave Without Artificial Light

Sandy Kinnee

June 2019

The Denver Post / Jeff Morehead

The Denver Post / Jeff Morehead

Imagine yourself on a mountain top or in the middle of a field of grass. It is night time. There are no city lights and won’t be for another fifty thousand years. As you tilt your face upward you gaze upon an infinite sea of bright tiny specks. Your outstretched hand cannot touch these points of light held high in the firmament. No stone you hurl will shatter their rest, in the way your rock disturbs a calm pool of water and sends ripples outward. Yet you can own these sparks that flicker out of reach with your eye and mind. These specks beg to be named, put into order and relations revealed.

A wolf may tip its head upward to howl at the moon and stars. But this wolf will not look at the clusters of lights overhead and impose a world of images: bears, lions, ibex, snakes, birds, or hunters. The act of naming and imposing or exposing structure is advanced and sacred knowledge. The vault of the night sky is a sacred canopy, a light bespeckled cloak of utter darkness.

Now imagine utter darkness, devoid of sparkling embers, where you might reach up and actually touch the canopy with your fingers. A ceiling of stone. Wall of rock. Floor as solid as wall and ceiling. You are deep inside Mother Earth, where the firmament is indeed firm. There is no deeper darkness no more silent silence than inside a gallery of stone.

You have a sacred task in the hallowed hollow of this cave. You travel on your belly, slither and crawl, carrying a small hand held flame, to a place far, far, far from daily life. Your journey leads you to a place where food is not consumed and everyday activities do not exist. Fasting, the exhaustion brought on by your arduous trek, and the disorientation that comes from a loss of daily reference points all serve to heighten your inner, spiritual focus. Here, deep in the cave there is no day. And while the lack of light evokes a night-like illusion, the moon and stars will never emerge. In this primordial sanctum sanctorum you search the canopy for patterns to reveal themselves. Here, your bears, lions, and ibex may be captured on the rock. In a sense, they beckon you to “draw” them out of the womb of Mother Earth. Your flickering flame helps you locate them, casting shadows to illuminate shape and form. Other mysterious forms and shapes are exposed and recorded by your scratching and marking. The knowledge revealed is sacred as is the method.

There is something extraordinary about being deep in a cave without artificial light.

Years ago I taught a course, as a visiting artist, during which I both took the students into an actual cave, one without prehistoric marks of any kind, and also afterward had the group construct a labyrinthine tunnel with cardboard boxes. They scavenged appliance, television, furniture boxes, every type of box a person might crawl through. Construction of the cardboard cave was inside a large college teaching studio. The resulting tangle of boxes filled the entire studio and looked like something between a gigantic hamster habitat and a homeless camp.

One by one the students crawled into the darkness of their constructed cavern, their intimate grocery store pony version of a secret, deep hole below the everyday world of chatter and too much monkey business.

In both environments the students were encouraged to use their personal flashlights only as necessary. Being inside this artificial grotto brought back long forgotten sensation of clandestine reading, after their parents had said goodnight, under their bed covers as a kid. I split the students into clans and invited them to make drawings someplace of their choosing in the cave. They would, as a clan, decide what to draw and determine if their drawings served their clan alone or might contain messages for the other clans. No written words, no cliché pictograms no references to modern life. Would they want their designs to be understood by others? Or secrets only for their own clan? Was their marking special knowledge or gibberish? Would they consider the possibility that they might leave messages for or beg indulgences of spirits that may dwell on another plane beyond the cave galleries? Did the drawings hold wishes or magic or only wished to be magic? Were they simply making marks because it was an assignment?

They could only mark with chalk, charcoal, and red oxide to make their marks on the cardboard cave walls.

If they preferred, they might simply sleep in the cardboard cave and make no marks. Or, make as many marks as they wished, so long as it was in keeping with the aims of their clan.

When in the actual stone cave, they also worked as a clan. It was not a cave in which they would be permitted to leave a single scratch or make a mark. Before they entered the cave they were told they would select two things to carry into the cave. Each already had their own flashlight and chalk, charcoal, and some red oxide. First of the two things they could choose to bring underground was a flat rock; as large a stone as they could carry in and out of the cave. The second was anything larger than themselves that would fit into their brains for easy transport. Picture yourself propping up a flashlight and making marks on a chunk of limestone, then carefully lugging it back out of the cave. Is the rock upon which the larger-than-a-person thing is inscribed heavier or lighter once it has left the cave?

What did the individual students learn about agreed upon symbolism? What did they learn about making marks with chalk on the floor of the cardboard boxes? What became of their marks when others slid past and over their marks? It went on and on. What did they learn about the magic of making marks? Or the lack of mystery? How much latent power is in a symbol or sign? The difficulty of reading someone else’s drawings? The inherent poetry or lack of it in the scribbles.

Each day I gave a short slide show and explained the history of the particular mark making innovation or change in perception. I wanted to put into context the developments, evolution of perception and as much as possible the intended target or targets served by this mark making. Why do drawings from this epoch differ from another? Who was the intended recipient of these lines and dots? In what way was the community served by these marks? What has self expression to do with anything? When did these scratches become visual communication? How do they succeed or fail? What is the value of a story drawn on paper compared to one told through moving images?

I thought that playing with cardboard boxes was a universal joy. Maybe I was wrong. Perhaps it is a strictly generational thing that has had its day and the world has moved onward.

This morning I found a little boy who looked at me as if I had told him the most boring and bizarre thing. I asked him what giant cardboard boxes meant to him. What was the biggest box he’d ever played inside? What was that box to him? A time machine, like the one from Calvin & Hobbes? A race car? A submarine? A Rocket ship? A square balloon, or a house, or maybe a cardboard cave?

No reply, other than a look of bewilderment. He picked up his squirt gun, one that looked like a real gun except it was hot pink and see-thru, then went out the door. Apparently, he had not played with an empty kitchen appliance carton, not turned it into an armored tank more powerful than a thousand hot pink squirt guns.

Like I say, maybe it is something kids don’t waste time with. Possibly the idea of turning a box into something other than a box is uninteresting and old fashioned. Or, perhaps big boxes, a twentieth century invention that replaced the wooden crate, are not so common as when I was growing up. Television sets were bulkier years ago and so were the old boxes in which they were delivered. Do refrigerators still come in large cartons? Cardboard boxes although a symbol of wasteful consumerism serve a secondary purpose of delight, a chance to flex the imagination.

When she was a little girl, I filled my daughter’s room with boxes and rolls of duct tape. Boxes she could butt end to end, weld with tape, crawl into as her own personal, protective, private cave. Her own labyrinth.

I believe imagination doesn’t need to be directed, nor should it. Let a cardboard box be anything it can be imagined to be. Cardboard is the second-best toy after a pile of sand. The trouble with sand is it gets in your eyes and you probably shouldn’t just crawl into a sand pit, whereas crawling into a box is safe. Inside a box you can be alone in a good way, with no fear of hitting your head on a stalactite, getting lost, running out of oxygen, or missing dinner. A cardboard cave has its place. Compared to a real cave, a unworldly and magical stony void in the ground, a cardboard cave is like a grocery store pony ride versus a bareback stallion or bucking bronco. Still, a cardboard cave is also a good laboratory for not only imaging, but in which to focus. Inside neither a cardboard cave nor a subterranean authentic is one prone to distraction.

There is something extraordinary about being deep in a cave without artificial light.

◊

Sandy Kinnee is yet another obscure artist who is an even more obscure writer/poet. Best known for his work with handmade paper since the early 1970s, he has for the past five years been exclusively painting fifteen foot canvases. He splits his time between Paris and Colorado. When in Colorado he paints. In Paris he writes because the apartment has no floor space for fifteen foot canvases.

sandykinnee.com