Negative Capability

Raymond Bally

July 2017

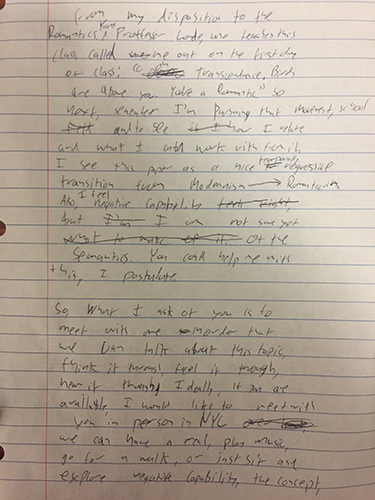

A Profile on Nix, Negative Capability, and Negative Capability

Near the end of the semester, Professor Londe asked his students to consider how they desired their Modern Poetry class to conclude, and then tasked them with using the final project as a way to create, satisfy, and substantiate that perceived culmination, whether it revel in resolution or discordance. Ray Bally recalls that on the first day of class, “The professor christened me a Romanticist.” He was oblivious to this aspect of his identity, although it was fetidly present. This set the tone for his experience with “Introduction to Modern Poetry”, in which he endured, enjoying the usually dissonant, but also diatonic clashings between the cultural movements. Under the mentoring guidance of Professor Mackowski, Bally has designed his next semester to be a romantic semester, in order to explore, and assess the nature of his sentiments towards this movement, and explore any direction that it suggests to his adrift being. While the young scholar advances closer towards obtaining his many desired academic degrees, Bally intuitively reverts in chronology of his studies of poetry to an earlier era, and views this project as a bifocal, transitional piece that is a temporary valediction to Modernism and a welcoming salutation to Romanticism. To accomplish these intentions, Bally plans to focus on John Keats’ concept of Negative Capability because of its origins in Romanticism and span into Modernism; however, the true motivation is that Bally, though not alone, struggles with securely grasping this elusive capability, since by nature, it is largely based on contradiction, abstrusity, shortfall, and ambiguity. Furthering the connection to Modernism, Bally will incorporate the perspectives and insights of Bern Nix, an avant-garde, jazz and harmolodic guitarist, a modernist in some sense, through one of their conversations, supported by Nix’s music and liner notes from his album, Negative Capability.

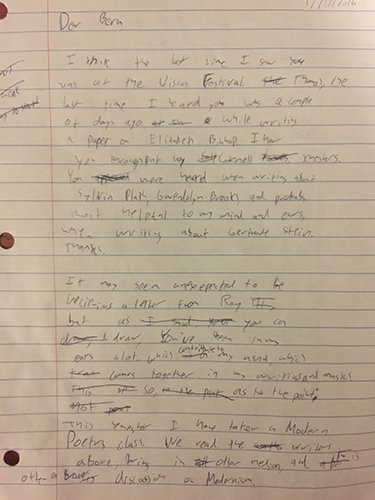

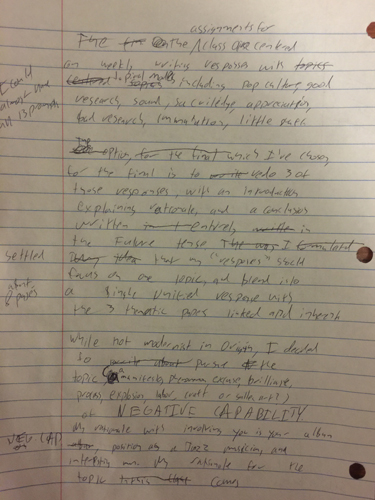

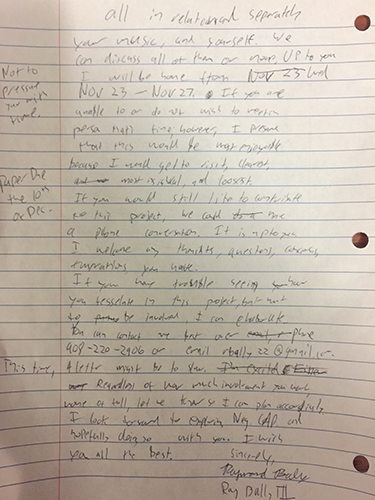

Bally, a fan and friend of the musician since a young age, reached out to Nix through a handwritten letter, in order to show his dedication to and draft an outline for the project. A few days later, he received a voicemail from Nix: “Oh, hi. This is Bern Nix to Raymond Bally the Third. I just got your letter, and I – I – well, I had trouble reading your handwriting. I just got your letter. I was trying to – I was reading it. Oh, well give me a call when you can.” Bally returned the call to explain the illegible letter and schedule a meeting with the man, whom he considers to be an expert on Negative Capability; this appellation ensues from Nix’s lifelong commitment to undiluted improvisation, role in the genesis and current preservation of harmolodics, and an earnest, heavy submersion while managing, effectuating, and feeling this slippery concept.

With a contained excitement and anticipation, Bally arrived at the guitarist’s Chelsea home and the two walked to a nearby eatery. As outlined in the letter, the young scholar believes he had not seen or spoken with Nix in a considerable time, so the pair began with talk about the present state of each’s life. Upon sitting at the table, Bally read “Ode on a Grecian Urn” in order to set the mood. With a grin, Nix responded, “ I can’t believe I actually memorized that.” He was making reference to an assignment he received in the ninth or tenth grade. Then, repeated the opening lines of stanza two: “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter” (Keats 296). After this reading, there was a long pause in which the two selected what food they wanted to ingest, while they digested the poem. He broke the silence with the unaddressed question, “Yeah – so – you know – what’s this paper going to be about exactly?” Bally is still developing the specifics to that answer, but he ameliorates this situation of consternation by citing Roethke’s claim of, “I learn by going where I have to go” made in “The Waking”, supplemented with Keats’ Negative Capability (McClatchy 44). Following a weak answer by the student, Nix says, “I picked the title for my album because it [Negative Capability] means being comfortable with uncertainties, being in the moment, being able to deal with contradictions, or the fact that so much of life is that we have to rush to judgments responding to what happens. So, the kind of music I play is within such a free, undetermined form; a lot of stuff happens.” Expanding on this, his liner notes rightfully present the concept as a liberating force because it “allows for comprehension, appreciation, and analysis without the need to rush to judgement; rumination and examination are paramount.” With the birthing of the term, Negative Capability, Keats averts the focus from the bleakness of the notion of humanity’s limitations in the ability to understand, and instead emphasizes that the stuff humans are not able to know is infinite; this asserts the creative, imaginatory power of humans to be boundless because the material for creation is not able to be enumerated, incarcerated, or enslaved.

Nix continues describing his experience as an artist crafting within the confines of the unrestricted realm of improvisation, creation, and uncertainty: “You have to respond to what’s happening in a given environment. You might have an idea of what you want.” Bally interjects by questioning whether Negative Capability is something planned and created. Nix denies that it is a choice, and takes the stance that it is more an occurrence, a precipitate that is inseparable from both its artistic and animate solutions: “Well you might have an idea of what you want, but it depends on what’s happening in the environment… You deal with the fact that, well, life is rife with contradiction. So, you try and accept it and keep on moving, which is often easier said than done.” Nix places the artist and circumstances in the cups of a balance, and it is the duty – the existence of the artist to balance the two to meet the intrinsic equilibrium, in which he or she has brought to the surface, for the creator and audience. He claims that the artist must “set a creative form as you go along. It’ll [the structure] have a form of logic, but not necessarily a linear or a traditional logic.”

To ground the conversation, Bally mentions his intentions to write about the sound of Negative Capability because acoustic meaning is a common feature in “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and Negative Capability. Nix appreciates this direction, but reminds Bally of the magnitude of difficulty when writing about this aspect: “Sound provides the meaning, it’s not what the words mean, it’s how they sound. In relation to music, music has no – people always talk about how hard it is to write about music, because music doesn’t have – a note doesn’t have the same verbal equivalent that a word has.” Nix elaborates by mentioning Gertrude Stein’s sound “being more important than the meaning,” the signified and signifier, and the process of deconstruction and analysis used by Ornette Coleman, whom he played with from 1975 to 1987 (Discogs). As an aside, Bally wondered because of these references, if Nix had secretly been in the Modern Poetry class, and wished that the musician would have delivered a guest lecture on Modernism.

This ode of Keats is littered with uncertainties heard in the abundant interrogatives, unexpectations in the tone changes, and contradictions. The speaker is mesmerized with the urn and at the end of the first stanza, he realizes he cannot fully approach and understand its narratives, emotions, and existence. He voices his fateful encounter with Negative Capability asking of the urn, “What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape / … What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?/ What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?” Next, the poet uses stanza two to identify and promote Negative Capability claiming, “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; / Not to the sensual ear, but more endear’d, / Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone”. Semantically, Bally is puzzled by this seemingly incongruent moment because Keats’ imagery plays to the senses, yet the speaker implores the urn to sing to the incorporeal; however, the young, negatively capable scholar does not get snagged on a rushed supposition or an evidenced interpretation, and instead leans on Nix’s statement of the essentiality of sound’s meaning. Bally is captivated and longs to hear the song that Keats prescribes, yet he and other readers do not have the capacity to acoustically perceive it with a “sensual ear”. How, then, can a reader respond to this imagery? Bally knows that the first step to insight requires the reader to give way to the Negative Capability of the line which demands a thorough, but relaxed steeping in the mind.

Though offering tangible tunes for the “sensual ear”, Negative Capability, by the Bern Nix Quartet, upholds the concept of its title. The seven tracks, all composed by the band leader, resist categorizations, despite loosely being Free Jazz. After the melodies, the songs change and depart into the unknown realm of contradiction and improvisation, which Nix believes is fueled by “the muse of music: that demiurge in the back room of the human psyche some call the unconscious.” For this reason, Bally feels as if he can only analyze the melodies because they are more manageable. The head of “Under the Volcano” begins as a funk groove with the band stressing two, big hits at the beginning of each phrase. Nix, on guitar, fills in the space with a yowling line that resolves every other time. The bridge has two lines, each with a single note, that are unbroken with a repetitious rhythm that ends, mirroring the start of the “A” lick, with consecutive, accented beats. Bally recognizes the latin feel in melody of “Naomi” and he likens the lyricism to an up-tempo ballad. Perhaps, the romantic Bally biasly gathers the ballad element due to the fact that a title is a woman’s name and his disposition to that poetic form. Nix’s comping behind the melody, played on Matt Lavelle’s trumpet, creates a healthy dissonance supported by the slicing drums of Reggie Sylvester and the jumping bass of François Grillot. The rest of the melodies are similar in their orchestrations, but vary in sounds and meanings.

Nix offers this insight about Negative Capability in the soloing: “See that’s the thing with free improv: so much of it is about – you know – after you play the melody, what do you do? Assume you’re playing something that has a thematic?” One direction the band pursues is allowing and encouraging solo sections to drift from the melody and its chordal structure. The listener can get lost and overwhelmed with the shape of the track’s unity and its moving confabulations. The band provides several answers about finding a makeshift hold. For example on “Fire Within”, Nix quotes the melody early on under Lavelle’s solo, but then quickly transmutes it by shifting its key, decreasing its attack, and lowering its dynamic until it disintegrates. This has a teasing effect because it leaves remnants of familiarity in the audience’s soul, while forcing listeners to move on. In this instance, Nix balances the artist-circumstance relationship. Negative Capability begs metaphysical quandaries: is the audience supposed to reflect on the fleeing moment of sound at the present, relate it to the melody and the title, or a combination of the two? Are the instruments to be heard as individual, as together, or both? These are similar to inquiries he encounters in poetry regarding the relationship of the word to the line, line to the stanza, stanza to the poem, and every other permutation of the poem’s correspondence with itself. Bally finds these essential questions to be unanswerable, unless approached through intuition in aim of somatic understanding.

When he conducts his own classroom one day, Professor Bally, though not now or ever an expert on this subject, will teach, with arduous authority, on Negative Capability. He will walk into the room, remove his tearing corduroy coat, and transcendently emit a romantic sigh from his lungs filled with the air of his life’s unknowns and contradictions. He will structure the course like the structure of a song, which conventionally contains an opening melody, sections for solos, for inputs, and for interpretations, and will close with a fading outro that has no end, similar to the future of Negative Capability. Keats wrote the melody that enunciated the glorious topic, but he claims he was not the first to work with it. He credits his predecessors, especially William Shakespeare, with creating the opening vamp to set the mood and stage for Keats to declare his melody superimposed on the harmony of his romantic contemporaries and every other artist and artistic movement that follows. For the improvisation section of the syllabus, Bally will bring in speakers, including musician Bern Nix, poet Joanie Mackowski, scholar Greg Londe, filmmaker Wendell Harris, and sculptor Barbara Wallace, to offer their insights on experiencing, understanding, recognizing, managing, and accepting Negative Capability. He anticipates that he will be asked at least once a semester how he became acquainted, obsessed, tormented, assotted, liberated, consumed with Negative Capability; therefore, to ironically avoid too much ambiguity and contradiction in a class based on those very topics, he will provide a copy of “A Profile on Bern Nix, Negative Capability, and Negative Capability”, regardless of the grade he received, to the pupils. He will watch their pupils dilate as they become struck with fear and awe as they realize their capacity to not know is limitless. Professor Bally hopes that they will not try to imitate him, as he once imitated Professor Londe, in the style of writing about themselves in the third person; though, he will not be able to stop them. Although it is likely to garner laughter, Bally will staunchly and honestly conclude the first and last day of class by quoting Nix: “Plus, I just like the sound of that term.” Simply, Professor Bally just likes and will always like the sound of that term.

Raymond Bally would like to thank Bern Nix for sharing his insights and creating fine music, John Keats for coining the phrase for the concept and creating magnificent poetry, and Negative Capability for making this paper possible. He could not have accomplished this project without the help of these three and all their contradictions, unknowns, uncertainties, and not-knowing.

Works Cited “Bern Nix.” Discogs. Discogs, n.d. Web. 09 Dec. 2016.

“Bern Nix on Negative Capability, Negative Capability, and Himself.” Personal interview. 26 Nov. 2016.

Keats, John. The Poetical Works of John Keats: Given From His Own Editions and Other Authentic Sources and Collated with Many Manuscripts. Complete ed. New York: Crowell, 1895.

Nix, Bern. Negative Capability. Perf. Matt Lavelle, François Grillot, Reggie Sylvester, and Bern Nix. Bern Nix Quartet. Rec. 16 May 2013. François Grillot, 2013. CD.

Roethke, Theodore. “The Waking.” 1953. The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry. Ed. J. D. McClatchy. 2nd ed. New York: Vintage, 2003. 44. Print.

ENGL 2070 Professor Greg Londe and Mr. Matt Kilbane

12/10/16- End of the Line = [(Sound + Appreciation)/Expert] ^Negative Capability