Abstraction and Beyond

Beverly Willis

June 2020

My thoughts and life-long observations about the elemental structure of physical form gave rise to the possibility of constructing of a visual language that creates ideas for expressing essential concepts of our times – as we drift away from the physical and into an abstract virtual world.

Throughout history art, such as murals, have been used to tell stories. For example, prior to the printed word and when most of the populace could neither read nor write, religion used art forms to communicate the message of God. A favored devise was that of triptychs – paintings of three, connected panels, such as Church’s triptychs, which told stories of Christ, his birth, work, and crucifixion. The triptychs also conveyed the idea of the relationships between the Holy Trinity and the family of Christ.

I used the painterly device of the triptych, combining it with an idea of a field of transformation. I used my geometric alphabet to explore these ideas. I developed this concept, while I was still in college. I have worked on it, on and off, all my life. This work is still unfinished. Following is a summary of my work to date.

First, I assigned meanings to my image alphabet, just like dictionary definitions, as follows:

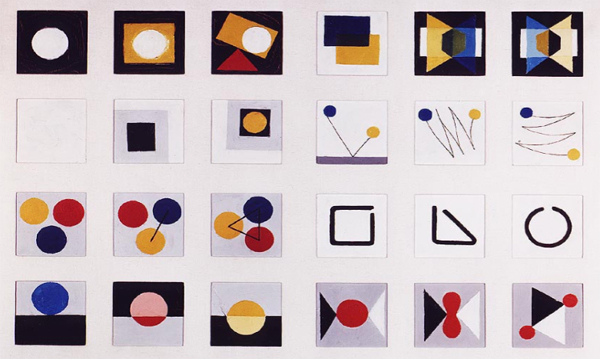

Willis Image Alphabet ², 1954-2020

Willis Image Alphabet ², 1954-2020

color – means identity and sets a tone e.g., with black and white being dualistic opposites, such as light and dark

triangle – means a force, or cause and effect

square/rectangle – means enclosure, a transformation field. Relationships are based on direction, opaqueness, and transparency.

line – means a beginning and an end, or a connector between point

circle/mass – means oneness, or a universe or one within universes, or an identity

point/circle – means an outline, or the process of becoming

empty/space – means a transformation field, such as interior or exterior space

I have now concluded that this line of inquiry is not valid. However I share here the below which represents my original thinking in 1959-1961 and first documented in 1991.

I painted a number of six inch square paintings in a triptych arrangement in oil with a palette knife on Masonite. I sought to explore different images that could be made that might match a word for which a two-dimensional image did not exist.

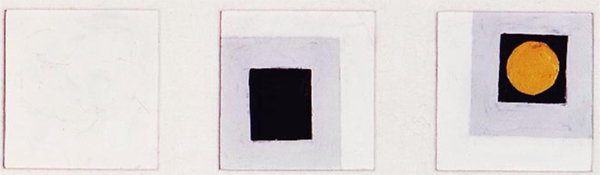

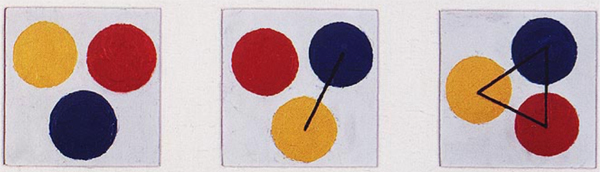

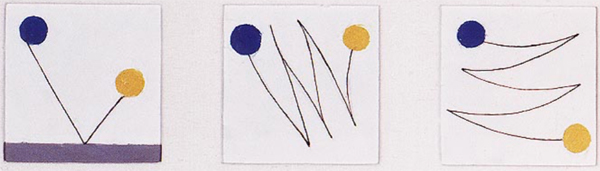

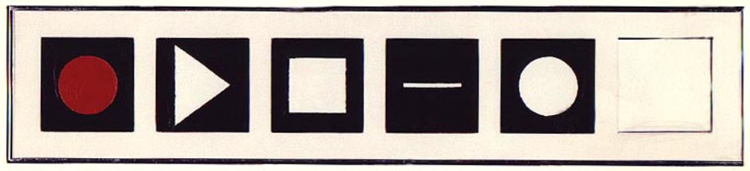

The triptych ideogram sequences define an occurrence in the process of change. The first frame of the triptych shows the beginning static condition where change is arbitrarily stopped like a film clip. The second frame shows intermediate action, the act occurring, the third frame the completed occurrence. The Transformation triptychs read as follows:

Transformation II

A single space becomes a dual space. An identity becomes enclosed in the dark space but remains a static identity regardless of spatial progression.

Transformation III

Transformation IV

Transformation V

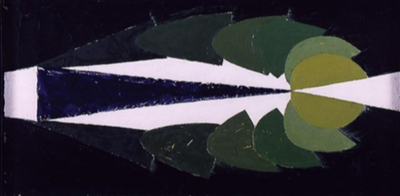

An identity is penetrated by light and dark forces, dividing itself into equal and identical parts.

Transformation VI

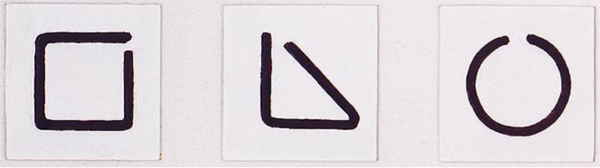

The line as a moving point can outline any image, including the circle, square, and triangle (the identity emerges when the outline is complete, and color added).

These transformations can be defined by single words. Words that have no pictures in current use. When the ancient scholar-artist-writer drew the lines that formed history’s first alphabet, the explanation of the meaning must have been difficult. Probably at first limited to just a few hundred words or less. As era’s passed the vocabulary grew, rules formed to govern writing.

Below is all eight of the Transformation Triptychs framed together, 24 total.

Written communication permitted society and government to develop computer programs, based originally on a simple binary, “x” and “o”. This abstract vocabulary, has changed work processes, extending the human ability to research and invent.

Opposition 1961, oil on Masonite

Opposition 1961, oil on Masonite

Opposition and Evolution are paintings using the Willis language.

Evolution 1961, 3 -1 ft. squares, oil on masonite

Evolution 1961, 3 -1 ft. squares, oil on masonite

What I have learned to date is the triptych format is not needed to make two-dimensional images of three dimensional objects or unseen matter that has meaning. But it has been useful in “thinking out” geometric relationships.

I believe two-dimensional images of three-dimensional objects are abstract. They become “real” to us through learning. The human ability to read two-dimensional graphic images and to understand them as “real” pictures is learned in the same manner that we memorize the alphabet and words. Pictures are taught at the same time as a child learns to read.

This realization came to me while I was an art student studying geometric abstractions in the work of Kandinsky, Klee, Mondrian, Albers, Malevich and van Doesburg. But not from those studies. Curiously, it came as I baby-sat for friends, earning extra money for my school expenses. I often watched my friends teach their children how to read. I observed a repeated teaching pattern. As I watched and listened, I began to realize that the child was memorizing the pictures and colors at the same time the child was memorizing the words and imitating the sound heard.

The mother would read… “Dick and Jane ran up the hill”. The child repeated the sound of the words, but interrupted the lesson to ask, “what is that?,” pointing to the hill. “That is a hill”, the mother replied… “And that?,” the child asked. “That is a barn on the hill.” Again and again, “what is that?” And so the conversation went. The book she was using was my own childhood primer “Dick and Jane”¹.

I then carefully watched other children learning. The process was always the same. The child’s mind was like a blank piece of paper and all imagery, the alphabet, words, pictures and colors were imprinted there through learning. All began “abstract”, all would be transformed into “pictures”, when the lessons were complete.

The point of the lesson was to teach the child to read, not to recognize or learn pictures. But learning images was being taught in the process of learning words and their meaning. The child would draw images on a piece of paper. Often those first effects were not recognizable to the parent, though meaningful to the child.

The role is reversed. The parent asks the child, “what is this”, and the child interprets, often saying “this is me”, or “mommy” or “daddy” or “house” or whatever. At some point either the parent or teacher will correct the child, showing the child an acceptable picture of the word.

The pattern of learning abstract images that become “pictures” occurs as the child learns the words. This is a sophisticated process. First the child must memorize the abstract symbols of the ABCs, as individually each letter has no meaning, until the child learns that these images can be put together into “words” and these words each have a separate meaning. The next step requires the learning of hundreds of words in order to speak the language, many more if fluently. The third step is to learn the grammar.

To speak and write either one’s own or a foreign language requires skill in formulating sentences. So the child’s task is to learn the rules of assembling the words together into sentences. The rules of sentence structure extend beyond meaning and are a form of art. Word phrasing like “me Tarzan, you Jane” may communicate ideas, but a civilized society takes pride in establishing precise rules and a “proper” form.

Rules governing words are extensive and categorize them into types and functions, e.g. subject-object, verbs, participles, as well as the correct sentence usage.

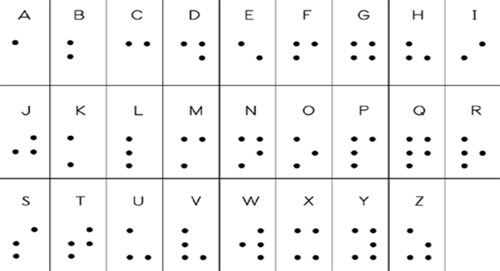

Chinese and Bulgarians have a different set of language symbols and rules, as did the ancient Greeks, Phoenicians and Hebrews. Or today, the Braille alphabet for the blind. The role of memory in all language acquisition, including visual representation, is undisputed. To learn how to draw a person, a barn, or any concept requires the memorization of specific symbols that are taught, or constructed, not innate.

However, the two approaches differ. The Chinese use pictographs. The Braille uses geometry. Note the difference in the two examples below.

Chinese Translation for English Alphabet

Chinese Translation for English Alphabet

Braille Alphabet

Braille Alphabet

Learning to imitate sounds, understand their meaning and images, learn the alphabet and words, and the rules of sentence structure occurs rapidly in the child’s early years. Memory of this process fades as the child focuses on learning other abstract images, such as arithmetic (number), algebra (number and letters) and the planar forms of geometry. Indeed, without the ability to master abstractions, we could not read, write, draw, or calculate. Early civilizations, using geometric forms and lines, developed images of what they could touch, such as human form and objects. Over the millennia, culminating in the Renaissance, painters and sculptors reached new perfection in graphic portrayal of people, objects and landscape. Giotto learned how to make form appear three-dimensional through the use of shadow. Piero della Francesca and Uccello introduced the concept of perspective in drawing. Michelangelo and Leonardo di Vinci assembled these technical developments into a dazzling display of painterly and sculptural accomplishment.

By the end of the 19th century, the impressionists, cubists, and abstractionists had begun a process of deconstruction, which among other accomplishments demonstrated that the eye and the mind were adept at recognizing and finding meaning in deconstructed images. Having learnt the details of representational images, the question was, could the eye identify the same image with simply a brushstroke or two? The answer was yes, which led to the next issue: that of completely erasing all graphic clues in order to study pure line and form for its own meaning. In 1926, Wassily Kandinsky said, “the general viewpoint of our day, that it would be dangerous to ‘dissect’ art since such dissection would inevitably lead to art’s abolition, originated in an ignorant under-evaluation of these elements thus laid bare in their primary strength.”³ He did not foresee today’s “coding” of computer software that creates digital images from a language simply of X and 0.

The abstractionists believed that underlying all was the geometrical form and an almost instinctual knowledge that somehow form was an essential building block. The pioneering abstractionists, in varying ways, gradually isolated as the most basic and abstract elements the point, line, circle, square, triangle, including the paintings black on black and white on white. They reassembled these elements in various configurations, testing visual interpretations. Perhaps seeking a new set of rules governing a new set of images.

One unstated premise was that society’s present system of graphic images was incomplete and new ones were needed. While the works of the pioneering abstractions relationally explored spatial arrangements of line, form and color, the resulting work became what could be called a transformation field through which the unseen could be seen. For example, our present system of “real” images, excluding language, numbers and equations, are limited principally to those objects that can be held or touched, such as a plate, human figure, a building, etc. Images, for example, do not exist for feelings or things that can be experienced or rationalized, but not touched. If a graphic recognizable image was to be made of the unseen, it must be transformed from the abstract.

The abstractionist work of the 20th century has explored a range of image elements. In my work I have used an alphabet of space, line, circle, square, triangle and color. This alphabet is no different than the ABCs of language. Recited, the language alphabet has no meaning. Nor, as geometric forms, does my alphabet. In language, the meaning occurs when the letters of the alphabet are assembled into words and these words learned. Meaning always has been adopted through custom and common usage and sometimes through centuries of use.

Geometry and its various decorative forms, whether connected or unconnected, underlie all matter. The idea from early thinkers that the universe is composed of certain geometric forms has been confirmed by present day physics and biology. Today science knows that much that cannot be seen with the naked eye is made of the derivative forms of geometry, both in form and proportional ratios, and applies to all biological matter. The geometric image of my alphabet is not new. Plato used a geometric palette to define elements of the earth and universe. Early civilization used geometric symbols to represent the unknown and mystical.

Geometry and mathematics were merged into an algebraic language to permit easy calculations and their communication. For example, a contemporary philosopher might describe the general form of mathematical communication in this manner: we have a definite system, we name its parts, and we adopt in many cases a single symbol to represent each named part.

Algebraic communication, which uses symbols to represent meaning, allows the formulation of relationships to be described. For example, the proportional rations of the golden section are noted as:

A:B = B:(A+B)

The small part is named A compared to the larger part named B. The formula is translated as follows: the small Part A stands in the same proportion to the larger Part B as the large Part B stands to the whole A+B.

These letters can be assigned numbers. The golden section in the beginning was constructed using geometry as a square within a circle, the sides of the square were assigned the number 1 and known as part B. Part A was them measured as .618. Part A added to part B therefore equals 1.618. Symbolically the ratio of the golden section can be used either through drawing (geometry) or calculation (mathematics). The two-dimensional language of geometry and mathematics is abstract, but universally used as a common language.

The next step towards accomplishing visual images for all words is to analyze words in the American dictionary. Many of these words have been formed over the years. I believe next step is to deconstruct the syllables within the words that have been used to construct it, such as “tion”, “Pre”, “con”, lyze and many more. Deconstructing sentence structure, and analyzing syllables point to the underlying building blocks of language and shows us how to invent new arrangements and meanings in verbal, written and visual communication that could possibly provide a connection or a functional use in areas, such as, machine learning or artificial intelligence. The image for the new, I believe, will be a single image, like that of the Chinese ideograms.

Our culture’s inheritance from the pioneering work of the early abstractionists allows the continuing development of the abstract into a realistic readable form, opening up new worlds of understanding for the eyes and mind to explore.

¹ Dick and Jane. Illustrator, Verna Sharp, author William S. Gray. Elson-Gray Readers, Publisher. 1930

² Chaos-Making a New Science. Author, James Gleick. Geometry of Nature, Viking-Penguin, Inc. Publisher, 1887, p. 99

³ Point and Line to Plane. Wassily Kandinsky. 1926, English edition 1947 for the Museum of Non-Objective Painting

◊

Beverly Willis established her art practice and used her multi-media art skills to support herself- upon graduation from University of Hawaii (1954) with a Fine Arts degree. Prior to enrolling at the University, she already had a one-person exhibit of watercolors at Maxwell Gallery (1952) in San Francisco. At the University, she apprenticed with fresco painter-muralist Jean Charlot, a founder of Mexican Muralism, and studied with Gustav Ecke, an internationally known scholar of Chinese History. Willis’s diverse studies and artistic research resulted in a multiplicity, sometimes contradictory set of ideas, of regarding the future of art. In this climate Willis’s ideas about an abstract visual language was born. Her ideas took on new roots much later with the development of the Chaos Theory and the invention of new imaging technologies of magnification that reveal the shape of actual particles that construct all organic things. Earlier Willis studied aeronautical engineering at Oregon State University, soloed at age 15 and received her pilot’s license at 18. Her career eventually expanded into Industrial design, then architecture. Her artwork has been exhibited at the Honolulu Academy of Art, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, and the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, NY.