Deborah Rockman Interview

Christine Hughes

March 2018

Culture Vulture 16

Culture Vulture 16

Deborah Rockman and I met in college. I immediately felt a deep connection to her that seemed pre-established. She is a very political artist and person. We did a telephone interview and then cleaned up her naturally irreverent language, I hope her spirit and her humor come through. I wanted to know how things have changed, the current shape of teaching, and to discuss her own work and activism.

She has written two books, Drawing Essentials which explains every aspect of drawing and The Art of Teaching Art, both published by Oxford University Press.

This interview will explain how one woman in Western Michigan has singlehandedly changed the way drawing is and will be taught. We did this interview by phone on Feb. 10, 2018.

Christine: How did you start making art to begin with?

Deborah: As a kid one of my goals was to be a perfect student in Catholic grade school, that included art projects. I took art classes in high school, I really liked it and knew when I went to college I wanted to somehow be involved with art.

C. You and I met at Western Michigan University in the printmaking department studying with Curtis Rhodes and Chuck Heasley who studied at the Tamarind Institute.

D. I was focused on printmaking. I was making drawings on litho stone and printing them so I could have duplicates of my drawings. I did some intaglio and aquatinting also. I ended up getting a Bachelors Degree in Fine Art with a secondary teaching certificate. Didn’t get a BFA, never had a BFA show.

C. I want to talk about your work and teaching and how they intertwine.

D. After my undergrad degree I spent a year teaching a graphic design program in a high school in Davison, Michigan. Didn’t like it. Too many limits placed on the students, who acted out accordingly, I didn’t want to be a baby sitter. My colleagues would sit in the teacher’s lounge and talk about gays and how horrible they were. I thought this is not what I want to do and I could get fired for who I am. At the end of my year there I got into an accident and was laid up for a year. During that time I decided to go to grad school to study drawing and printmaking. After researching I applied to one school and was accepted at the University of Cincinnati. I had a full ride. Back then admission to grad school was almost always free. It was late 1970s and early 1980s. I had a relatively good experience. All my teachers were men with one exception. I learned a lot about printing from two Tamarind printers, but in terms of the ideas in my work and talking about concept and content I didn’t get much. I felt I learned more from my fellow students. I knew by then I wanted to teach.

C. Was it a pretty conservative school? It is on the Ohio River. It’s the Mason Dixon line, right?

D. No, by then I was out, I was openly gay. Most of the faculty were quite a bit older, from a different generation they weren’t full of vigor! They sure didn’t interact with me the way I interact with my grad students.

I did all sorts of stuff to earn money. Freelancing as a graphic designer, teaching college level courses, nude modeling. Bizarre because I’d be a model in a figure drawing class, then I’d teach a drawing class to some of the same students who had just drawn me nude.

C. That would not happen today!

In all these years in college did you ever have a mentor who you really looked up to for guidance or support?

D .There was a woman who had a tremendous influence on me in Grad school. She wasn’t studio based but was an art historian. She also taught performance art classes which was just beginning to happen. I took every class I could from her. I think I also had a crush on her. I have actually been trying to find her.

Jo Face. She had a real impact on me. She was so passionate about what she taught, knew, felt. She was clearly a feminist. She wasn’t an artist but she was very creative. She took us on trips to places to experience them. River beds..And brought in Mary Beth Edelson who worked with both grad and undergrad students doing performance art.

C. So, you have been teaching your whole adult life. You’re now a Professor of Art in the drawing program?

D. Yes. I started teaching in 1980, when I was in grad school which were all two year programs then. Just before my MFA show opening I had friends and family over, and got a call from University of Minnesota in Moorhead offering me a job teaching the fall semester. I was there for two years. I will always be grateful to them for giving me my start. When I first went out there I was replacing someone on sabbatical and when he saw the job I was doing he decided to retire and I got the position, but I couldn’t stay there. It was way too isolated out in the middle of North Dakota and Minnesota. The winters were beyond brutal. At the time as a young lesbian woman I didn’t feel I would meet anyone I could merge my life with so I made one of the most radical decisions I have made in my life (it won’t sound radical to others) but I resigned after two years without another position to go to. I went to my family’s in Michigan. I got called for an interview at Kendall, which was a couple hours away from where I grew up and they hired me. I’ve been there ever since.

C. While we are speaking about teaching, tell me what can you teach about how to make art? You can certainly teach someone the aspects of drawing, composition, working with the correct materials, perspective and so on, but can you teach “making art”? Do you address that in your teaching or is it more simply technical?

D. It’s very different teaching foundation courses than teaching graduate courses. My first twenty years, Kendall didn’t have a grad program yet, I was teaching all levels of under grad. My focus was mostly teaching students how to see in a way they were not accustomed to, then translate that onto a two dimensional surface. When I got to the mid and upper levels we were talking about their ideas and what they wanted to explore in their work and how to do that without it being an illustration. I told them I’d much rather see a work I don’t totally understand and when I walk away am still thinking about it, than to see a work that is a one-liner. Illustrations are meant to be understood by anybody. I had to work hard to get them to understand that learning to draw representationally is a great skill which teaches one about seeing and materials use but when you get to the upper levels we aren’t saying you have to work that way. In fact the drawing program at Kendall is really mixed media, painting, knitting, sculpting, everything. We love that.

C. Yes, the definition of drawing has changed radically since we were in college.

D. It’s easier to say what drawing isn’t than what it is. It is very broadly defined today. I write about that in the forward to my books. Drawing has been resurrected in part because it is understood as fundamental to everything else, it also can be portable, and not usually engaging with a lot of toxic materials.

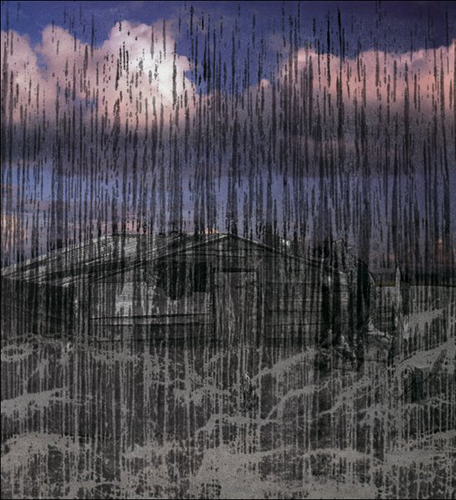

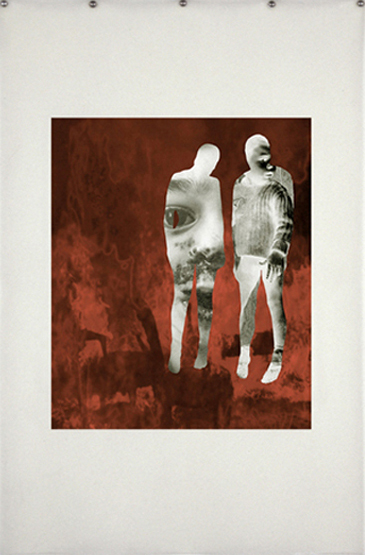

The Space Between Us (2)

The Space Between Us (2)

C. How has teaching changed for you over the years?

D. I‘ve taught a few different generations. I used to be almost the same age as my students, now I’m older than their parents if they are traditional students. The biggest thing I’ve seen impact the tenor of my students is the digital age. Young people have a lot going on in their lives, they are at the point where they are trying to figure things out. I am always asking them questions getting them to talk openly. With the generation that has grown up with computers, cell phones, social media, attention spans are different. Secondly, I am not accustomed to walking down the hall and seeing faces in cell phones, faces looking down, no eye contact. I embrace technology for what it can offer but it’s had a negative impact on college students who now have enormous amounts of social anxiety because of it.

C. Making art takes a lot of focus, attention and self direction. Is the shortened attention span evident in students work or are they compensating by gathering other’s images?

D. The availability of images online is overwhelming. Also the ease of research online is great, as long as one is vetting the information properly and investigating the sources of information. Student’s lives have been impacted so many different ways .I have never had so many struggling students, I mean emotionally, with where they fit into society, with the leadership in our country, the debt they go into.

C. What are they thinking they will do with a BFA or MFA in Fine Art?

D. They know they can do all kind of things. We have professional development classes we have students who own businesses, students who have gone to grad school and are now teaching, running commercial art businesses and students who are professional artists! Maybe it’s because I’m working with students at a college of art and design. They are committed. I follow my students and I know when they go to grad school. I write letters of recommendation for hundreds of students. I have hundreds of letters on my computer from over the years. Everything is mediated digitally. They have the false idea that they are connected to others on social media, but they aren’t really connected, I have just seen a huge difference between my first students, then students from twenty years ago and the students I have today. I see higher anxiety. When I started teaching most students, if they had a job, it was for 15 or 20 hours a week, now most of my students are working 30 to 40 hours a week and going to school full time. They are exhausted. They have no supplies. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve bought materials for them.

C. Even with their full time jobs they are going to come out of college in a lot of debt.

D. They have that hanging over their heads which you and I did not have. Higher ed is now running on the business model. They are eliminating as much as possible, especially tenured full time faculty. Many of the faculty are adjuncts who are not required to be present other than when they are teaching. They don’t have an office, don’t keep office hours. They don’t have to be there. How are students supposed to connect with the faculty? At Kendall we have a faculty to student ratio that’s not super high. I really get to know my students.

C. Is there a short answer to how student work has changed over these years? Or is that too general a question to even attempt?

D. I‘m thinking of it more as how society and culture has changed. There is a lot of interest in addressing social and cultural issues on the part of students that’s done in very different ways. More awareness of marginalized groups.

C. Yes, that’s happening across the board in the art world. How much of that is your influence with your students? You have always been personal and political in your work.

D. I talk a lot about that in a class I teach which is a bridge between foundation level courses and the more advanced level called ”drawing materials and processes” which is very much about materials and process, but also about idea generation. I force my students to address these issues. I tell them you may never do this again once you leave this class but there is no shortage of political and social material. I have students from very diverse backgrounds.

C. This segues nicely into talking about your work. You always work in a series.

D. I get on a thinking track, it’s often what is currently being addressed culturally. I’m not interested in doing one piece about it, but instead explore this by doing anywhere from ten to twenty-five pieces, until I feel finished. That typically leads to my next idea which is always related to what came before it.

C. So you come to a place where it becomes rote, and you stop?

D. When I feel I have addressed it in a way that can have an impact on people, and have exhausted that. I keep circling back. Right now I am playing with language again.

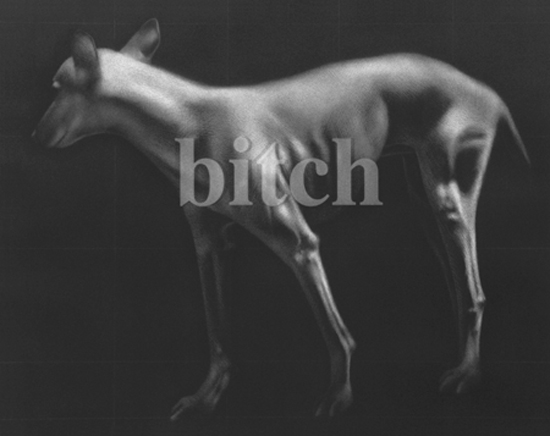

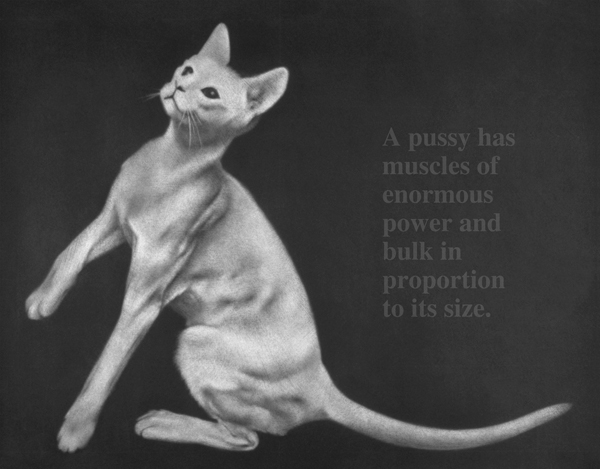

A Pussy has Muscles

A Pussy has Muscles

C. One of my favorite series was “Word War”.

D. Yes, that was my feminist self back when there was a lot of discussion about what words you could and couldn’t say. It‘s still something I deal with. What you can and can’t call a woman, and gay people. I can call myself queer but some straight middle aged white guy better not call me queer! Coopting the language which is used against you. I loved working on that series, very aware of the parallel between terms used to reference animals and women. “A pussy has muscles of enormous power and bulk in proportion to it’s size”. I got that quote from a British book about cats. Reclaiming words often used derogatorily. Recently I’ve been seeing in social media, men referring to other men as twat, cunt, pussy. I respond, but taking my time so as not to be reactionary and their responses have been “oh my gosh, your’e right, I’m sorry”. Cunt used to be a very positive reference to the sacredness of women, women’s bodies. Most of us don’t know the history of these words which are now used in a derogatory way.

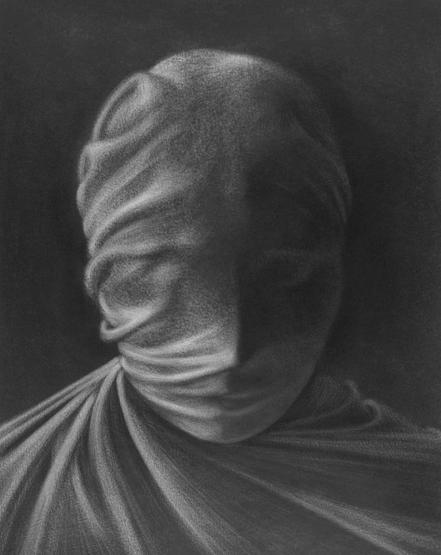

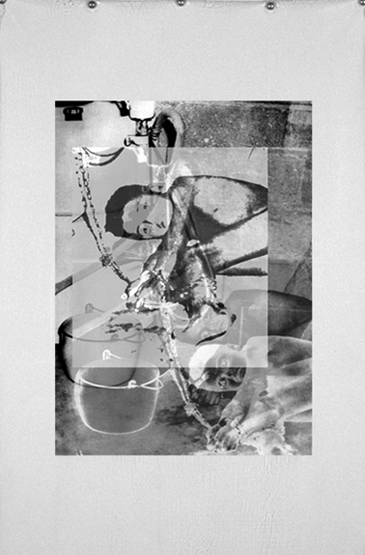

Study #2 for Death Dream

Study #2 for Death Dream

C. You did a series which “Visions Dreams Memories” what years?

D. That was the first intensive series I did after I got back to Michigan and started teaching. I was trying to find my own voice and persona. I was doing a drawing here and there while at MSU, but I was mostly focused on teaching which I think is an enormous responsibility.

C. Writing the books you did certainly comes from that feeling. You’ve written two books for Oxford, one on teaching?

D. Yes, It’s published through Oxford’s scholarly division “The Art of Teaching Art”. I want to do an updated version. It’s sold well but it’s outdated. It references slides, projectors and other now outmoded technology.

C. Was that your first book? How did you come to write that book?

D. I just decided to do it. To teach teachers how to teach. I had a lot of shitty teachers in under grad school. They were rarely in the classroom. Their primary goal if they were straight men was to bed down the female students. It infuriated me.

C. I always tell people that I learned how to mix colors being a house painter, not in art school. I don’t think we were taught very much of anything with the exception of the printmaking department because it was so technical and things needed to be done in a certain process.

D. Yes, I learned a lot of the technical aspects of printmaking but I wasn’t challenged as a student. It was the 1970s, women weren’t taken seriously.

C. On your own steam you just sat down and wrote this book teaching a teacher how to teach art?

D. Yes, I had been thrown into teaching in grad school with no preparation at all. When I was teaching I was on my own and realized how much I didn’t know. There are things you know intuitively when you are making art that you don’t know how to articulate. My first book was the result of all the handouts I prepared for my students. I also did lectures and the students were amazed at how much they understood. You couldn’t assume that anybody knew any of it!

When I got to Kendall we had to teach a full semester of perspective drawing. I didn’t know perspective and the class was fifteen weeks long. I wanted to challenge my students. I was on a year sabbatical, I spent the last 4 months of that sabbatical before school started and I taught myself perspective.

C. Which brings us to the second book which has the longest chapter on perspective I have ever seen! I had no idea there were that many aspects to perspective!

D. Hell yes! In the third edition I have perspective broken into two chapters. First is the essentials, the second is advanced where I go into the more advanced stuff, and there are still things I don’t cover like cast shadows, reflections etc. I taught myself how. I got so many different books. I would find contradictions from one book to another about how to do scaling; how to move a subject back and forth in space and make it look right based on a horizon line. I had to figure out which was right. I did hundreds of technical drawings, many of which are the illustrations in my book.

C. I saw the Hockney show at the Met recently. In one of the large paintings he worked from an old treatise on perspective, by following the instructions he did a very strange painting. We at first thought was a fairy tale. A woman in the upper window of a building was leaning out, holding a candle and lighting the pipe of a man on a distant hill! Hockney was playing with perspective based on this instruction. So you have become the master of perspective.

D. I’m not using it a lot at the moment and when I do I refer back, but yes, I know a lot about it.

C. You have a lot of really great student work in your book “Drawing Essentials”. Are these your students?

D. When I first wrote “Drawing Essentials” yes, they were all my students. When I built the drawing program ten years ago, which allowed for a BFA in drawing rather than a BFA in fine arts with a drawing concentration (I was chair of the program), I found other good student work I wanted to include. If it is someone else’s student the faculty member’s name is noted, otherwise they are my students. It all comes out of Kendall with a very few exceptions from my first years in Minnesota. One of my goals in writing these books is to highlight Kendall’s Drawing Program.

C. Is Kendall funding your writing these books? Does Oxford give you an advance?

D. No. But I get open access to student work. No advance, but I have re-negotiated my contract. For my first two books I had to do all the research, track down Master works, get permission, pay at least half of the fees to use these works, which became impossible! The fees kept going up. Seurat, Rembrandt, Michelangelo and so on. They wanted me to use Old Masters. For the third edition they wanted twenty more Master’s works. I said I’d do it but that I believed student work was far more instructive. I had a battle over the covers on the second and third editions. My editor wanted some really bad Nineteenth Century drawing of a limp hand with a sphere in the background! I said no! I am addressing contemporary drawing!

The Space Between Us #2

The Space Between Us #2

C. Your work has always been personal but also political. You push it. Your work has always made me somewhat uncomfortable. Children born in the “right” place to the “right” family juxtaposed with the very much less fortunate.

D. A painful lesson I learned in that series was I was putting the less fortunate in the background and foregrounding the fortunate ones. What the hell am I doing, so I switched it around.

C. What is the name of that series?

D. “The Space Between Us”

C. You’ve been using digital imagery in your own work for the last ten years?

D. Yes, not quite ten years, but I started with “The Space Between Us” which is a combination of my drawing and digital images. The hand drawing with colored pencils was done on Mylar which sits over the digital image.

C. What about the series “Losing Sleep” is that both as well?

Untitled 1VA

Untitled 1VA

D. That is almost purely digital using Lazertran on handmade sheets of acrylic medium. I wanted them to be like skin. I look back on that series and there are pieces I wish I’d never done. It was a hard series, really graphic in some pieces. I did most of that series on sabbatical in 2003-4. I had a large format black and white laser printer and discovered Lazertran and I wanted to work with it.

C. You are teaching in Grand Rapids, Michigan home of the ArtPrize, the largest monetary art prize in the world.

D. It used to be $250,000 chosen by public vote and $250,000. by professional vote, now its $200,000 in both those categories and additional smaller prizes.

I have objected to it from the very beginning because it puts professional artists on the same level as hobbyists, and because the public vote gets the same weight as the professional vote. I will send you the email I sent to the Executive Director last year.

C. You had death threats the first year. Didn’t you need a body guard following you around? You were interviewed about it in The New York Times. Is that what got everyone up in arms?

D. The first year, as soon as they announced it, all the artists in Western Michigan got together and decided it was going to be a train wreck. To give the same money to the public vote as to the informed vote!

C. How do the public vote?

D. It’s all done digitally. It’s grandma and grandpa walking around with the grandkids who point at a sculpture of a dog made out of tin cans and the kids go crazy for it and they vote for it. We don’t expect the general public to understand sophisticated contemporary art. The fact that the monetary prizes are the same is an insult to every professional artist who enters. I am not, however, saying that all the professional art is good.

C. And the idea that anyone can make art now. As a matter of fact Andrew Edlin (who started as an outsider dealer when I was active in the field 15 years ago and now owns the Outsider Art Fair) A few months back did an open call to everyone to make a small work to be included in a show, stating specifically that you didn’t have to be an artist at all. Was his thinking that he might discover some “outsider“ whom he could then market?? (America’s Got Talent??)

D. Amongst uninformed general public, particularly in West Michigan there is no appreciation for the time, effort, money and sweat that go into being a professional artist.

C. You have to have some education in art to understand what you are looking at to begin with. One needs to understand the Language of art.

D. These are the arguments I have been making for years. Big conservative money, the Devos family, Betsy Devos’ family is in charge. They don’t want it to be perceived as professional or elitist. It became evident to me the first year when I raised my hand and asked younger Rick Devos if he wasn’t afraid that crap would be voted for by the public. My wording was much more professional, but this was the essence of my question. It made the lead on the news that night, it was in all the newspapers. The names I was called on TV8’s website, even though they state at the top of their website that they dont allow derogatory language. I was called a cunt, a bitch, an elitist. Email after email. They never removed these from the site. This was a display of the ignorance of many of the people there who don’t understand when you go to school for years to earn a BFA, an MFA, that’s called a professional. That was the beginning of it. The second year all of the press was trying to track me down again and I had threats being made again. When I served on the jury for the International Award I had to be escorted to and from my building to the engagement because there were so many threats made against me. It got really ugly. Every year I’ve complained about it. I’ve been interviewed several times and now after nine years people still call and ask if I have anything to say. This year they gave a $200,000 award to someone who made a portrait of Lincoln out of pennies.

C. Yes, we all saw it.

D. There are templates on how to do it all over YouTube. It’s nothing original. Because it’s Abraham Lincoln, it‘s patriotic! This is a very conservative part of the state. My friends and I were raising hell. I wrote a very long email to Christian Gaines, the Executive Director of ArtPrize, saying that the award should be rescinded because there is nothing creative or professional about it. He sent my email to the President and Dean of Faculty at Kendall, like I was going to get in trouble! My history, what I saw as a kid really impacted my work. It was emotionally upsetting.

Untitled B1

Untitled B1

C. How much of you original impetus to make art came from that?

D. I felt vunerable, in danger most of the time and started looking for extremes of that in my art. It all started with my feeling that anyone can have a child. Then it became about other issues, children in constant danger, or in poverty. In the end it became about children, and the impoverished people who do the best they can in impossible circumstances, and now I am investigating refugees and people in war torn countries. It was not my direct experience, but I felt really on the edge of that much of the time. I could see it in extended family members, child abuse, poverty, alcoholism, addiction, mental illness, and violence.

C. I suppose you would call yourself a political artist. What makes your work so powerful is that it’s not just a political statement, one can intuit your feelings within the work.

D. I have more compassion than I know what to do with. It’s so frustrating because I want to make a difference. I try to make a tiny difference where I live and want to through my art also. But I have never had gallery representation in my entire life.

C. You’ve been in so many shows, in collections, received grants and awards…

D. I’ve just been nominated for a distinguished teaching award as I come upon retirement. What I wanted to do was make a difference in peoples lives, I have done that by teaching more than in any other way. I am not just teaching how to make art, but talking to students about what they’re struggling with. I’m like a godmother or something. I don’t shy away from their need to talk about personal things. I know where to send them for help if it‘s way over my head. They know they can talk to me.

C. Do you think your students make more personal work because of it or does it just help them to function?

D. Both.

To learn more about the work of Deborah Rockman, click here

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Painter Christine Hughes has been working recently with imagery of compost which serves her interest in natural forms and affords subject matter vague enough to become abstracted in a way that she refers to as physical abstraction. She studied at Detroit’s Wayne State University and worked as a consultant in helping to build a collection of visionary self taught and contemporary art. Her recents show have been with Art 101 in Williamsburg and John Davis Gallery in Hudson.