Interrupting Siqueiros: San Miguel & LA

Randee Silv

December 2013

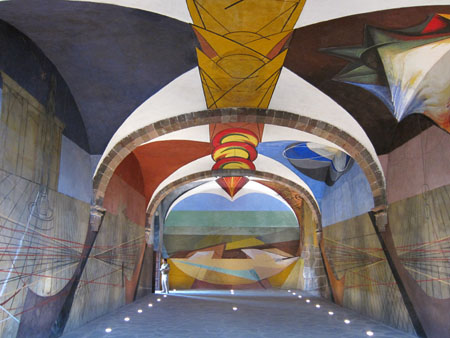

Recessed spotlights lined the floor replacing the once hanging single bulb. All details could now be witnessed. A few loosely sketched black figures and motifs juxtaposed with bold, colored geometrical shapes intertwined with a multiangular web of lines that crisscrossed the stone walls, reaching onto the arched ceiling where a corkscrew lightning bolt flashed the distance. No matter from which direction I turned, riveting surface forms jetted towards me, shifting, curving as I tried to follow them. Impossible to stay still. Almost dizzy, I stood on the embedded footprints left by Siqueiros.

Getting off the bus in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, Iʼd had no idea that Iʼd find an unfinished David Alfaro Siqueiros mural tucked discreetly away in an 18th century convent. I waited as people left to hear my own voice resound with what remained.

All I could find out was that Siqueiros had left the project in the late 40s after a political disagreement with an administrator from the Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes. The National Institute of Fine Arts acquired the rundown building in 1962, establishing the Centro Cultural Ignacio Ramírez – El Nigromante in honor of the San Miguel writer, atheist and progressive thinker. Theater props had been stored in the room until 1997, when Vida y Obra de General Ignacio Allende went on view for the centennial of Siqueirosʼs birth.

Before leaving Mexico City, I hoped to unravel more details at the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, where heʼd been living until 1960, when with his wife Angélica Arenas at the wheel, the two were followed and chased by Secret Police. Falsely accused in connection with a teacherʼs strike turned violent by Mateos regime provocateurs, Siqueiros was charged with social dissolution to silence his open, unyielding political honesty. Angélica, joined by four years of worldwide protest, finally won his release.

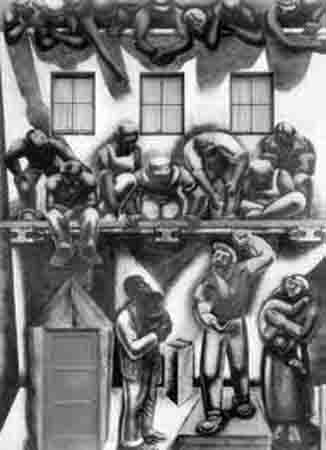

The museumʼs coordinator for documentation, Mónica Montes, filled me in with what she knew about the mural and what had happened with the schoolʼs director, Alfredo Campanella, but with our language limitations, I knew Iʼd have to keep digging. Leafing though archival photographs, I noticed one where the room was covered with illustrations that detailed the life of the San Miguel born national hero, Ignacio Allende, a leader in the 1810 rebellion for Mexican Independence. It wasnʼt clear why this earlier version had been abandoned.

Exiting through the lobby, I was drawn to the slick black angles, racing optical shapes and blunt concentric circles that Siqueiros had painted, floor, wall and ceiling while converting the building into an art center in the late 60s. Surprised, I had to wonder how abstraction fit in with his political ideology. Noticing my interest, the guard recommended Siqueirosʼ final monumental sculpture-painting, The March of Humanity on Earth and Towards the Cosmos, Misery and Science (1965-71) at the Polyforum Cultural Center, a must see.

Walking into the domed, diamond shaped auditorium, panoramic bas-reliefs advancing and receding from every direction swept me among the masses through oppression and exploitation from darkness to hope. I retreated into the mosaic flows of color crescendoing to the sky, imagining how Siqueiros might have expanded San Miguelʼs abstract platform into yet another cinematographic narrative.

It turns out that the Escuela Universitaria had been bought by Campanella, a Mexico City lawyer with limited interest in the arts, in 1946 from Felipe Cossío del Pomar, an art historian and exiled political activist who was returning to Peru. With the programʼs approval under the U.S. GI Bill that same year, he was anticipating financial gain from direct payments of tuition grants.

Resourceful and connected, Pomar had hired Stirling Dickinson, an aspiring writer and artist, to run his modern art school in 1938, once the cavalry regiment housed in the convent was kicked out. Dickinson had recently landed in San Miguel on the invite of the famed opera tenor, José Mojica, whom heʼd once recognized on a train to Oaxaca. Mojica was leading a coalition to promote San Miguel as a magnet for cultured tourists. Film stars, composers, singers, intellectuals, local politicians and artists showed up regularly at his soirees.

To attract serious artists rather than dabblers, Dickinsonʼs brochure read, “For students of discriminating taste, situated in beautiful surroundings and under the direction of renowned international instructors….the faculty of the school is of the first order, including the most famous Maestros of the Latin American Renaissance.” 10,000 were distributed throughout the U.S., Canada and Latin America.

It wasnʼt until Life magazineʼs January ʻ48 issue referred to San Miguel as a “GI Paradise” on a $65 monthly allowance that 6000 eager veterans applied for the additional 100 spots that Dickinson thought the quiet town could handle. But, there wasnʼt the distinguished faculty as advertised. Complaints appeared at the American Embassyʼs Veteransʼ Affairs office that might jeopardize the schoolʼs finances. Campanella, no supporter of Siqueirosʼs politics, found no choice but to invite the acclaimed painter as a visiting professor.

Gachita Amador, who was now living in San Miguel, had married Siqueiros as he was en route to France after having fought in the Constitutionalist Army during the Mexican Revolution, but their revolutionary fervor and social theories collided with those of the Parisian avant-garde. Traveling to Italy with Diego Rivera, Siqueirosʼs evolving anti-formalist concepts were further clarified by the frescos of Giotto, Masaccio and Michelangelo mixed with the visual aesthetics of the Italian Futurists. When he returned in 1922 with Gachita, the new democracyʼs Minister of Education, José Vasconcelos, had already put artists on the payroll, commissioning public murals to preserve and advance the nationʼs culture and uplift and educate the future society.

The ambitious muralists, impatient and distraught by workersʼ responses that their efforts had neglected to directly confront the conditions behind social and economic struggles, turned to the Mexican Communist Party. On their advice, Siqueiros, Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and others joined the party and organized the Union of Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors to redefine the responsibilities of monumental public art, turning to Mexicoʼs pre-Christian, pre-Conquest art to reassert their countryʼs indigenous identity.

Gachita wrote for the unionʼs satirically illustrated newspaper that was pasted onto working class neighborhood walls. El Machete printed Siqueirosʼs manifestos and challenged government wavering from revolutionary promises. But it ended with an ultimatum, publication or future mural contracts. It was Gachita who encouraged Siqueiros to accept Campanellaʼs offer.

Five consecutive lectures on the Mexican Mural Movement electrified the air. The students, spellbound, rallied around Siqueiros to demonstrate his modernized techniques. Campanella, in a strategic response to accusations of pocketing studentsʼ tuition among other criticisms, offered Siqueiros $1500, the price of two portraits, to return and complete a mural with his students as apprentices during the first third of each month before Independence Day. All material and travel expenses were to be covered except for the pricey hotel bill at Campanellaʼs ranch, where he and Angélica would be obliged to stay. Seeing the possibilities for applying his polyangular methods toward reinventing the architectural space of the nunsʼ dining hall, Siqueiros agreed.

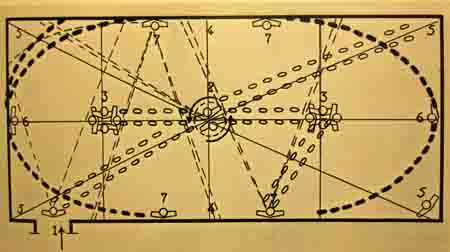

Collaborating with 24 students and faculty, he first analyzed the architectʼs colonial design that was to be integrated within a modern composition. The team took precise measurements. They determined all the viewpoints of a moving spectator. Photographing the empty room as a sketching technique, they constructed a wire model that replicated the diagonally crossed ellipses dividing this long rectangular chamber into sections. What Iʼd originally thought were Siqueiros drawings in the photograph at the Sala de Arte turned out to be an assignment done by students before the old deteriorated plaster had to be removed.

The room was then washed down with potassium cyanide, followed by two coats of cement and clear primer. Siqueiros had already shifted away from mixing dried pigment into water with cactus juice to synthetic paints, adding to his palette vinylite, which had been introduced for the manufacture of LPs, and testing mineral spirit based acrylic resins before a water soluble version was available to the market. Having designed a moveable scaffold, the students marked the surface with traversing 45 degree lines and simple forms as Siqueirosʼs hand intuitively mapped the harmonic relationships. Broad zones of color were rapidly painted with industrial spray guns. Images were photographed from multiple viewing perspectives to adjust visual accuracy from any angle.

But then Campanella began complaining about escalating material costs. Fearful of endangering the schoolʼs status with the VA, he rejected Siqueirosʼs suggestion to approach wealthy patrons. Now having an internationally prestigious artist at his school, Campanella tried to slow the project down by extending Siqueirosʼs term and insisting that all his time be dedicated to the mural, which would of course interfere with additional income he needed from easel portraits. Siqueiros tore up the amended contract. The promised money stopped. Time Magazine reported that Siqueiros had pushed Campanella down a fight of stairs. Siqueiros circulated a letter of protest.

I did not abandon the work nor cancel the contract…. I only refuse to collaborate with Alfredo Campanella who happens to be director of the school by reason of a mercantile operation of hypothetical legality; he lacks the most elemental knowledge of the general ideas of the plastic arts….and it could well be that he….is causing harm to the young foreign artists….; he had the audacity to make me an offer that would change the contract and involve me by complicity in those ready-made pleasures that the school had produced over the years….or perhaps rather, a provocation to exclude me from possibly being a witness to the same.

Students refused to attend classes. Faculty walked out. Mexican artists joined the boycott and accused Campanella of awarding fraudulent masterʼs degrees. Campanella charged Siqueiros of plotting to take over the school. Secret FBI files alleged that Siqueiros was trying to “convert American war veterans to communism.” The U.S. government withdrew funding, forcing Escuela Universitaria to close.

Dickinson and faculty immediately reorganized as another school. Campanella publicly branded them as “rabble rousing communists.” Accompanied by Siqueiros, teachers handed President Alemán their leaflet, A Good School, Not an Educational Racket, which helped gain official approval. Aiming to shut them down completely, Campanella then bribed journalists and recruited the townʼs anti-American priest in a smear campaign while conspiring with a U.S. attache to sabotage their VA eligibility. Siqueiros and faculty member Leonard Brooks made one last effort to persuade the embassy directly, but officials conveniently blamed a new U.S. regulation. Instituto Allende opened with its own resources. However, Campanella still owned the mural site, which prevented Siqueiros from ever completing the project.

Yet I saw no signs that it had been whitewashed as were his 1932 murals, Street Meeting and América Tropical, in Los Angeles. Siqueiros had opted for exile over continual house arrest in the village of Taxco. There he met the founder of the Chouinard School of Art, who mentioned a teaching position in downtown Los Angeles. Siqueiros secured a six month visa for himself and his wife, the Uruguayan poet, Blanca Luz Brum.

Siqueiros was given the schoolʼs courtyard wall for his advanced fresco class instead of a traditional interior space. This challenged him to revolutionize Renaissance processes, replacing wet lime plaster with fast drying waterproof cement and pioneering the use of spray guns and airbrushes for their speed. The composition developed from documentary photographs and, spurred by his conversations with Sergei Eisenstein, incorporated the dramatic psychological impact of montage in igniting his visual kinetics. Siqueiros remarked that “The still camera and the motion picture camera for the first time in history offer us…the subtlest and amplest elements of space, of volume in space, of movement in all its complexity.”

Street Meeting infuriated conservatives with its multi-racial crowd rallied around a union organizer on a city corner. It was ordered removed by the LAPD Red Squad. Only in 2010 did Autry Museum curators discover, while researching for the exhibition Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied, that the mural still exists. The Chouinard Foundation is trying to buy the building back from the Korean Church and see the painting preserved.

Near City Hall, on Olvera Street, known for its history of labor and political activism, the Plaza Art Centerʼs director, F. K. Ferenz, commissioned Siqueiros to paint a billboard scale, 18 x 82ʼ mural on the Italian Hallʼs 2nd floor rooftop wall that overlooked the busy square. The buildingʼs owner had requested a lush, tropical, festive Mexican marketplace scene to promote tourism, a theme Siqueiros despised and had no intentions of painting. Instead, during a time of factory closings and anti-union policies, where both Mexican and Mexican Americans were being targeted for deportation, Siqueiros painted what he described as “a land of natives, of Indians, Creoles, of African-American men, all of them invariably persecuted and harassed by their respective governments.”

Assisted by his Bloc of Mural Painters, source images were gathered, projected, outlined and airbrushed in just two weeks. Late into the night, right before the unveiling of América Tropical, Siqueiros added an indigenous laborer lashed to a double cross with an imperial US eagle perched above, while two guerilla freedom fighters, a Peruvian and a Mexican, crouched ready to take aim. Some praised it as powerful and masterly, while others, labeling it communist propaganda, were terrified and wanted it to disappear. US authorities, already concerned that his work might provoke social unrest, refused to renew his visa and deported him to Argentina.

Siqueiros managed to reenter the US unnoticed in 1936 to represent the Mexican League of Revolutionary Artists and Writers in New York at the American Artists Congress, a collective forming to oppose war and fascism. Siqueiros organized a series of experimental workshops entitled A Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art at his loft studio on 5 East 14th Street. Rueben Kadish, Philip Guston, Sande Pollock, Millard Sheets and Harold Lehman from his LA painters syndicate, along with Razel Kapustin, Jackson Pollock and others participated. Kadish felt Siqueiros had “liberated young painters from all sense of prejudice and orthodoxy derived from academic art.” Declaring easel painting dead and discarding the “stick with hair on its end”, they poured, layered, hurled, dripped, chopped, burned, spray gunned, stenciled, splattered vibrant colors of pyroxylin, the automative industryʼs newest enamel paint, onto masonite and asbestos panels on the floor, watching, imagining, pursuing forms as they emerged.

As part of the “Art for the People” workshop, they constructed a float for the General Strike for Peace and May Day parade where a giant mallet, marked with the hammer and sickle, repeatedly struck a ticker tape machine that spat paper out over a Wall Street capitalist holding an elephant and donkey in his outstretched arms. If it werenʼt for police restrictions and a choppy ocean on the July 4th Anti-Hearst Day, another float would have sailed past the crowded Coney Island beach aboard a small boat carrying two figures sitting back to back, each sharing the rotating interchangeable heads of Hearst and Hitler.

By the late 60ʼs, with its whitewash fading, América Tropical began to reappear. Judy Baca, artist and founder of the Social & Public Art Resource Center, felt that “we saw this as a symbol, an aparición” that inspired, energized and shaped the Chicano mural movement. “This artistic occupation of public space forged a strong visual presence of a people who….lacked representation in public life.” Even though América Tropicalʼs deterioration was considered too severe, it sparked a community campaign to save the mural. Working with activist art historian Shifra Goldman, Jesus Trevinoʼs 1971 documentary film helped to raise its public visibility.

Siqueiros had specified that the mural was not to be repainted and had offered to replicate its central section before his death in 1974. In 1988, in an uncanny continuation of his commitment to cutting age methods and materials, The Getty Conservation Institute began the long process of reintegration using digital photographic technology. After the GCI and the city had spent 9.95 million dollars, the mural went on view for the centennial of the Mexican Revolution in 2010.

Securing an alleyway wall in Culver City for the 2012 Latino Heritage Month, Siqueirosʼs great-grand niece, Anna, brought together muralists and graffiti artists to paint an homage to Siqueiros, La Voz de la Gente! The executive director of the Mural Conservancy, Isabel Rojas-Williams commented that the artists, in their reaction against LAʼs 2002 Mural Moratorium, had the “sheer passion of all to break the chains that have prevented artists to express themselves freely and legally.” The city finally lifted the ban this past August. Rojas-Williams added, “We owe it to our next generation to reclaim our legacy as a mural capital of the world.”

While LAʼs Chicano artists were hearing Siqueirosʼs call for an “art of the streets…on the most visible sides of high modern buildings, in the most strategic places in callejones, in working-class districts, in Union Halls, in public squares, in sports stadia, in open-air theaters,” Mexicoʼs emerging artists showed little interest in aligning themselves with Siqueirosʼs political-artistic ideology or the government patronage that had sustained muralism. Declaring it a nationalistic cult, groups like Ruptura / “The Breakaway Generation” and Nueva Presencia / “New Presence” looked towards international trends as well as their own individual freedom of style and context.

Siqueiros told Newsweek:

I am a citizen artist, not a Bohemian. I donʼt believe in a world where each artist is a little god, each one with his own philosophy, each one with his own little kitchen to fry his abstract ham and eggs. The only bad painting is the one dominated by the individual ego. In Europe a private market has determined a private art. In Mexico the rich prefer to collect cars and many wives. They only began to buy pictures fifteen years ago. Here our art is for an audience of millions. Easel paintings whisper to a private few. Murals shout out to the public.

Vida y Obra del Gral. Ignacio Allende, photo: Randee Silv

El Machete, photo: Philip Stein, Siqueiros His Life and Works

Harmonic Correlations Map for San Miguel mural, photo: Como se Pinta un Mural, David Alfaro Siquerios

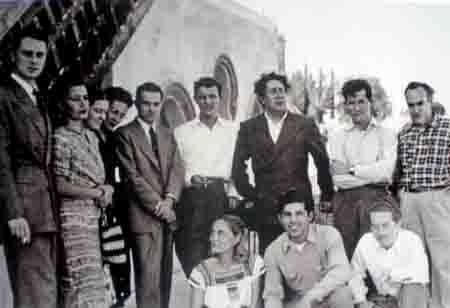

Siqueiros with Students in San Miguel, photo: The estate of RA Smith

Students Spray Painting Street Meeting, photo: Mark Vallen’s Art for Change

Street Meeting, 1932, photo: Chouinard Foundation

América Tropical, 1932, partly whitewashed, Los Angeles, photo: Times Archives

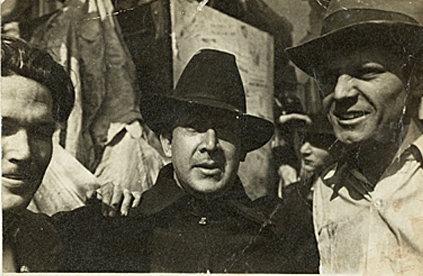

George Cox, Siqueiros, & Jackson Pollock in New York 1936, photo: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

David Alfraro Siqueiros, Self Portrait (El Coronelazo), 1945, photo: Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City