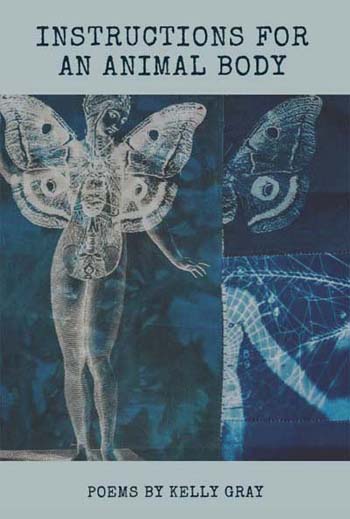

Kelly Gray’s Instructions For an Animal Body

Kathleen Florence

October 2021

Kathleen Florence in conversation with Kelly Gray on her new book of poetry published by Moon Tide Press, and the northern California forest that inspired it.

I had a babysitter who threw kittens into the pool from the balcony. Short shorts and hair sideways boombox convertible cigarette. The way she would sing and wink, like I wasn’t there. Men with ink and greased ease, a leer for her bend.

Denim fringed inside thigh, smooth.

– excerpt from “Instructions For an Animal Body”, Moon Tide Press, 2021

KF: You live with your partner and daughter in a wooded area that could be the setting for many of your story-tale poems. What is it like to live there and what is your day to day like?

KG: I have never lived anywhere for more than two years except for my home now, and I have been here almost nine years, which I mention as an indicator of how much I adore it. It’s the first place I have planted roots, quite literally, in the garden, but also by raising my child here. I think some people see my life like a vacation postcard. I work from home which means I am gazing out onto mossy redwood trees and befriending deer families and squirrels. Other people have an innate fear of the forest, they seem rattled when they arrive, wondering about ghosts and predators, and more recently fires. And… all of this is true; they are not wrong.

future painting of quail

future painting of quail

KF: From the outside there is a romantic idea of the artist’s life as a vacation, as something removed from the world, which is both true and false. The forest is a dark metaphor for the artist’s life, for any life.

KG: One of my favorite children’s books takes place in the “dark and sunny woods,’ and that’s a metaphor I hold, that the shadows seem all the more dark in the forest, but the light is multilayered under the canopy. Plus, one must dedicate a certain amount of time negotiating with the forest about who gets to be where- vines and roots and insects and rodents are constantly making a play for “my” space, and I am often wrestling with my writing in the same way- from micro issues such as words to larger themes taking up space. The forest gives me a lot to work with. Winter is cold, summer is evacuation. It can be lonely, also a much-needed refuge. It has given me a lot of time with myself, and a lot of time to understand the forest as one organism- which I am a part of. If you are an observer, it becomes evident that the mycelium, roots, treetops, the fallen giants, scat, bramble, all of it is constantly pulling elemental forces up and down, back and forth. The underworld is exposed as much as the sky. Sometimes as a writer, I feel like I am just pulling shit this way and that, but I am in good company.

KF: The thread of animal embodiment runs through the collection of poems, but throwing kittens stands apart. It feels like Amy the babysitter is forcing an innocence out the window. How did this poem come to life?

KG: Part of my childhood was spent in Southern California, where, for many reasons, I was miserable. Amy was a young woman who personified a culture that seemed out to engulf me, and I was resistant as I was entranced. It’s a fuzzy memory, and yet the feelings are vivid: a desire to sacrifice my own values to be accepted. I included this poem because, like all of us, I have not been in right relationship with myself, animals, and the world. I hope that if anyone were ever to look at my body of work, including this collection, that they can see that I have an eye towards my own complicity. I have been desperate to get “Amy” to love me. As an adult, I can see that Amy was as much a child as I was, looking towards those men to take her in. Later, in this collection, I mirror that same desire, and suffer for it. We have all thrown kittens into the pool, one way or another.

KF: The mother-daughter connection is another subject that floats up in this book. How do the threads of inclusion, separation, obligation and connection weave and unravel when choosing to write about your child?

forest friend

forest friend

KG: When I think of my child, I see this thoughtful human who is filled with shining light. But I know that my own motherhood is very dark, claustrophobic, and insecure. This has nothing to do with my daughter and everything to do with my own experience of childhood, belonging and protection (or lack of). I hope that I am not writing about my child, but of my own struggles and awakenings. I am very aware that I feel bound to my child in a way that no one was bound to me as a child, and this is bittersweet, as well as draining, because mothering while motherless is a particular hardship.

KF: Your writing doesn’t back away from the layered and complexity of being, including but not limited to mothering.

KG: I can be a mother who is tired who is feverishly reading the Dream House by Machado locked in the bathroom and purchases a pair of Frye boots for way too much money on my phone in a moment of self-loathing while spending too much time on social media and is thinking about rape culture and the connections between beehives and socialism while watching porn and remembering I need to pack my kid’s lunch and therapy is in five. I am much more interested in that poem than just a poem about loving my child to pieces.

KF: Is there an expectation that your daughter will be an artist like yourself and your partner?

KG: Ha! It is less of an expectation and more that she has declared it so. My partner now is not her father, but her father is also a writer with an MFA, and her grandfather is an accomplished photographer, and my mother was a potter, and grandparents on both sides were painters, and really it just goes on and on. We have examples of artists who make a living through their art, and examples like myself, where it is a passion, but I have a day job (several, actually). I do have a soft spot that if she asks me for a pet or art supplies, I will do everything I can to get them for her (thus all the washi tape and a Husky).

artwork by London G.

artwork by London G.

KF: My parents were also artists with day jobs, so I understand this connection, which you’re right, is less expectation than the child’s desire. My parents were more concerned that I would be poor. They both grew up in the Depression era.

KG: I’m worried about her growing up in a world that is dying, and not always knowing how to talk to her about the great loss ahead. I do talk to her about what it would take to follow her passions, that I regret reaching mine later in life, and what privilege is and how to use it. She has always been a prolific creator and I already see her immersed in things that didn’t exist when I was a child- she’s deep into video editing and digital art, and she has her own podcast that she has produced completely on her own. I am telling you it is the best podcast ever about animals and is designed for little kids. Seriously, this is not even mom talk, it’s that good.

KF: Speaking of your partner, the painter. His paintings and your poems seem to naturally respond to each other. Is there intentional collaboration, do you ever disagree about aesthetics, and what can you tell the reader (who may not be an artist or living with one) what is inspiring and difficult?

KG: Gage often says he paints towards poetry. In my work, I hope to use imagery to evoke feelings while avoiding using direct descriptors for emotions. I think we have that in common, that we both use placement and light and omissions to discuss themes of grief, loss and what we find beautiful, while at the same time trusting our audiences to come to their own conclusions. We see the same sights daily, tend to the same flowers and trees, and we often read to each other. We both believe that love is a form of attention, and we pay attention to the same land, shadows, pain and kindness in each other. So, often our work is dealing with similar themes, but I would not say we ever intentionally collaborate on individual works, at least not with anything we have shared publicly thus far. It’s more like we create on our own and then say, oh, we should totally share this work together.

KF: Artists create families of artists. As spouses, with children, with friends who are also artists. We create our own communities and values extensions of ourselves, works in progress.

KG: Yes! And like most families, we must go deep to keep the ties strong. We’ve had deeply complicated and sometimes messy conversations over the role of the artist, our obligations, and how to determine our own success. Gage has decades of public work behind him, and it is his day job as well as his blood and breath, whereas I feel like I am just getting started after years of watching and listening and privately developing my voice. I have a lot to learn from him, but often learning is hard, and we are both so freaking sensitive.

KF: Yes, we take things personally because what we do is personal. Every act of creativity is, but factory-thinking, amongst other things, has caused erasure to our connections to each other, to the earth, to what we do and who we are.

artwork by London G.

artwork by London G.

KG: Yes, most of us are born and die in for-profit institutions where intimacy is shunned. My work is deeply personal, alarmingly so to some people. Which means sometimes, I am writing about Gage. I have shared pieces with him that upon first reading, pushes him towards feeling exposed. So, we wait. When he comes back to the work, he may see it in a different light. We have a system in place that allows us to vet what goes public and what doesn’t, but I am not very patient, so that is hard for me. And I have had to learn that sometimes, he can’t comment on my work, because it moves him so much, or hurts him to know that I have been hurt by the world. Having someone read my work and then say nothing is worse than someone saying this is shit, so I have had to adjust and not internalize his silence, while teaching him that I am not looking for feedback on content, but on craft. That’s been a helpful distinction for us.

KF: We are mirrors that look for cracks and flaws, though we also look to improve.

KG: Reflections are a theme we both play with, literally and otherwise. Gage paints me once a week, but I have never seen the paintings. This is my choice. I am nervous that I will see them and not like how I look which could come across as me not liking the painting. So, I leave the final product alone and just fall into the experience. I get a lot out of observing him while he is painting me, it’s like watching someone have sex or play music when no one is around. He thinks he’s observing me, but I am so still, and he is so alive. It’s a trip.

I think I have always been an observer. Whether I am attending a birth, or community organizing, or wildlife tracking, or working with birds. Third eyes abound. The machine world wants to take away our right to observe. Storytelling is one antidote to that. When you are good at storytelling, you are observing the past, your audience, and your telling all at the same time. I love the complexity of that position, it’s like you are a walking time machine creating a new future as you go.

bone collection and Gage painting

bone collection and Gage painting