New Industrial Music

Thomas Park

February 2017

Those of us who live in an urban environment are subjected to a multitude of noises coming from machines and, sometimes, from loud human beings. I imagine there will be some study on this, but intuitively, I think there is an even greater quantity of sustained noise with relatively fewer dB’s than big noises like explosions, ambulances or screaming babies. The latter simply draw more attention. It is not until the air conditioning is turned off or the street is closed down for a market that we realize that there was something more on top of the silence, or what, innocently, we believed silence. – Miguel Parera Jacques

A genre of music called “Industrial” has been around for decades. It began with the band Throbbing Gristle, in the 1970’s, and at the time was characterized by strange or unusual themes. This preponderance for the weird or spectacular reached a peak in the 1990’s in Chicago, where bands like Ministry and Skinny Puppy used drum machines, heavy metal guitars, and sampling keyboards to create particularly aggressive sounds and vibes. Early Industrial music drew its name from the “Industrial Revolution”, and was associated with a world changed by big business, industry and urban living.

The main reason a “New Industrial” music is relevant is that the urban environments it connotes are growing. More and more people live in cities each year. The entire West Coast of the United States is close to becoming one megacity. Although some cities are not as prominent as they once were, generally cities are becoming places of choice for people to inhabit, and that is a trend that is worldwide.

I am in favor of creating a mythic aspect to the city– living in cities has become so common amongst people that places like the DMV, the Industrial District, the Bus Stop, Train Station and other locales are now parts of mass consciousness. These and other locations have their own sights, sounds and smells. As a musician I am interested in exploring the sonic palette of such places– of capturing or rendering their aural signature. How many millions of people have waited for a bus? Or boarded a subway?

Modern cities are often trapped in outdated, decaying infrastructures. How much more evocative is the train track or train yard when only a few, rusted, archaic cars lumber along those lines each day? Maybe this is the sad magic that “UrbEx” photographers pursue when they risk life and limb to enter old buildings that have remained unused or misused for decades. What does the reality of global warming mean about the existence of large smokestacks, whether they billow chemical smoke, or not? Has some of the city become mythic in that it persists as ancestral memory, from the days of our parents and grandparents?

I would suggest that, in our current culture, the authentic music of the city is rap music. Rap is the only genre that captures the energy and danger of urban environments. The problem with rap is mainly that it relies too much on the human voice, and the city is more vast, more depersonalized, and less individual than a voice can evoke with any success. Rap also suggests a link with African (and hence African American) culture, and though a “New Industrial” music must encompass this kind of experience, it should not be limited to it, but should conjoin experiences of people with all backgrounds and histories who have come to cities to settle. A “New Industrial” should be more like a “Statue of Liberty” of music, welcoming all to come gather.

Being places for masses of people to work and survive, cities involve a depersonalizing quality. That is necessary, as the resources of the urban environment function for a broad spectrum of people with different needs. The bus works for us all (or as many as is possible), the courthouse must allow us to pass through and have our say and experience, and since we are all involved, not one of us particularly is, but us as a community. Hence the depersonalization. A new industrial music should capture this effect as well, being similarly accessible to many people, and similarly abstract or non-emotive.

Further evoking a depersonalized quality is the lack of greenery in a city– where many square miles of concrete and asphalt edge out grass, shrubs and trees, people feel cut off from their nature and hence from their roots. It is the job of “New Industrial” to make this experience aurally tangible.

If there is an emotional spectrum for the structure of cities it would be awe, and perhaps fear. Awe over the size and scope of its structures, their ability to be rendered inaccessible, the sense that they represent institutions that are beyond our control. Fear that a person might become lost or need help and be unable to find it, shut out by the millions who do not know them or by the buildings that house necessary resources. Third Reich architects consciously made structures disproportionally large, to dwarf and intimidate individuals. This effect is attained without intent in most modern cities, where huge skyscrapers are locked and secured and made places where many are not welcome.

It is possible that a certain “New Industrial” music could be used to counteract the more automated, mechanical or intimidating aspects of city life. This type of music could serve as a remedy for the parts of life (and other musics) which overstimulate. By using elements of our urban environments, but portraying them in certain ways—for example, with longer phrases or sustained tones or sounds, a composer promotes a sense of time that reaches beyond the current mode of “Jetzeit”. This type of “drone” music, can easily be part of a “New Industrial” genre. In the words of Gerald Fiebig, “In recent decades, new forms of ‘drone music’ have emerged across a variety of electronic and even rock-based musical idioms, from ‘drone ambient’ to ‘drone metal’. What they share is an interest in very slow musical developments, sometimes bordering on stasis. Listening to such sounds is very different from much of our musical experience, where variety and tempo are what we usually listen out for. But drone sounds not only challenge our listening habits, they also go towards de-programming our everyday modes of behaviour, which are usually geared towards speedily, efficiently working through our everyday chores both at work and in our private lives. In fact, sociologists such as Hartmut Rosa have argued that the continuous acceleration of modern life since the beginning of industrialisation is now reaching, or has already reached, a point where human beings tend not to be able to cope with it anymore. Drones offer a possible antidote to this development. They invite us to listen closely to very slow developments, offering us time out from the constant rhythm of ‘speed and efficiency,’ giving us a sonic canvas on which to develop our own creative ideas.”

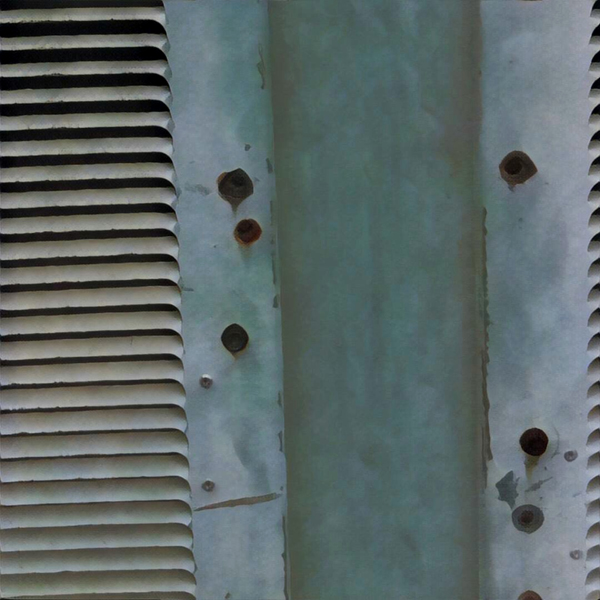

Moving on to other specific musical elements, texture can be a quality in music as well as materials. Cities are full of textures– largely due to the man-made substances that comprise the buildings, streets and other structures. There is metal– both in its new, polished, “clean” aspect, and in its old, rusty aspect. Concrete, freshly poured and cracked by time and elements. Asphalt, black and smooth and faded and warped. The juxtaposition of old and new in the city makes this so. How do these visual textures translate into music? What does rust sound like? Or cracked concrete or pavement? Can you hear the edge of a slab of concrete? Moreover, the city has a presence– a continuing existence in consciousness. Can we use sound to evoke this presence– the reality of the proximity of an urban environment, with its man-made, profane, polluted traits?

Many musicians have used traditional instruments to connote the city. I suggest that simply recorded sounds, using devices of varying sophistication, could be relevant. Recordings can be listened to directly, sampled and composed, or sampled, treated, and assembled after these processes have been applied. Effects such as granulation, distortion and reverberation can accentuate certain aspects of urban recordings. Effects can especially bring out texture and scale. Recordings could be made in both micro and macro environments– capturing larger-scale scenes, and smaller scenes such as equipment devices and atmospheres of individual apartments or other enclosed areas.

Urban sounds can be gathered more directly at sites of construction or demolition, where power tools, bulldozers, saws, drills and other equipment interact with the cities’ materials. This type of sonic environment tends to be more active and high-decibel, furnishing sounds that stand out above the ambience. I think it is better to shy away from using such sounds in this type of music unlessed they are processed and focus more on capturing the city as an atmospheric experience, and construction and demolition sited protrude sonically.

Noise as an aspect of music has been explored. There are some (such as Luigi Russolo), who suggested that noise should be the main element in a new kind of music. Others, such as certain rock bands in the ’90s, used noise together with melodic elements to create a “wall of sound” effect. Noise is part of the urban environment. I would suggest that cities are elements where noise has become yet another color on the sonic palette. There is more to urban sound than noise, but it would not be complete without it. A “New Industrial” music should reflect this.

In another context, the reviewer, Miquel Parara, refers to an idea conceived of by musician Chris Reider, called “Inclusive Music.” Inclusive Music can be atmospheric, but it notably invites listeners in. Sound added by listeners, from their own environment(s), becomes part of the piece itself—in performance, it changes depending on where it is performed or who is tuning in. This notion is relevant to a “New Industrial” music, in that abstract, atmospheric pieces connoting the city could easily be enhanced by “actual” sounds of the city—added, as Reider theorizes and Parara suggests, by city dwellers themselves, and especially if the atmospheres capture and render the more generalized sounds of city life.

I think it is time to ask why we called Industrial Music “Industrial”, and to think about re-rendering in music the environments which this word connotes. I hope that musicians and listeners will consider the ideas represented here, as well as the techniques, and explore a new movement in music, using the “Industrial” moniker, but replacing guitars and drum machines with recordings, actual and processed, of real urban environments. A music less focused on overstimulation and spectacle than the original “Industrial” music—which allows room to muse and meditate, both on our surroundings and on our lives, in general.

Photos and treatments by Thomas Park

Thomas Park

http://www.mystifiedmusic.com .