Of Long Tones & Zips

Daniel Barbiero

April 2016

“The concern with space bores me. I insist on my experience of sensations in time—not the sense of time but the physical sensation of time.”

-Barnett Newman, 1949

Imagining Barnett Newman While Playing Long Tones

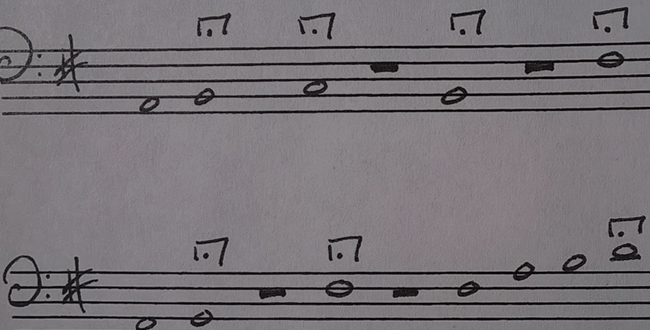

Think of a performance on a string instrument consisting of long tones bowed with long pauses in between. Imagine at the same time a typical zip painting by Barnett Newman. A parallel immediately comes to mind: The one structures sound and time in the same way that the other structures the visual field and space.

The parallel emerges most clearly when we think of both in terms of plasticity, that is, in terms of the dynamic relations between and among elements, whether musical on the one hand or pictorial on the other. But first a phenomenological reduction of sorts: Consider Newman’s painting strictly in terms of their structural or compositional qualities, not in terms of the extra-formal associations Newman claimed for them.

The premise is this: The long tone against the audio background is analogous to the zip against the field. The gestalt is somehow similar, even if the tone intervenes in and divides literal time while the zip intervenes and divides pictorial space.

In other words, the zip divides space the way the long bowed tone divides time. Both take place against a background of only apparent emptiness—a background that can stay background or can, through a shift of attention afforded by the work’s structure, emerge into and as the foreground. (In fact Newman’s negative spaces are painted, and ostensible silence is filled with ambient sound.)

In both painting and performance, we encounter the same basic dialectic at work, only couched in different terms: The visual field and the zip; the audio environment and the tone. From this dialectic emerges a distinctive compositional ambiguity.

Start with the painting. The zip establishes the painting’s internal relationships—between the painted stripe and the field, between the parts of the field on either side of the zip, between the pictorial space and the edges of the canvas. But it also establishes the painting’s external relationships, that is to say the relationships between the painting as an object and the space surrounding it.

The simplicity of the motif and its linear form—the latter drawing the eye beyond the confines of the picture plane (obliquely alluding to the definition of a line as an infinite progression of points extending indefinitely in both directions)—makes of the painting less the representation of something else and more of an independent thing. An object taking its place among a world of objects.

There is also the matter of rhythm. The zips appear with an imprecise regularity resembling the rhythm of breath.

Consider now the plastic values embodied in the long tone against the pause.

When playing long tones divided by substantial instances of silence, it’s natural to hear the focus as falling on the silences, on the open spaces that, inevitably filling with unintended ambient sounds, refuse to stay open. And certainly that is one possible artistic goal of playing music marked by long silences. But here the goal isn’t to attempt to illustrate a philosophical point about attentiveness to the ambient sounds surrounding a musical performance—and by extension, one’s everyday life–or to point up the ontological reciprocity and interchangeable status linking the intended and unintended sounds in a performance. Rather, it is a formal concern, one which treats negative space as a compositional element pertinent to the performance’s overall texture—its episodes of greater or lesser density, intensity, its horizontal and vertical organization and so forth.

As a formal element silence helps define scale and opens the performance out to engage time.

There is an existential dimension here not to be overlooked: This is time from the lived perspective, the experience of time in this setting by this person by virtue of this performance. To play a long tone is to divide time in the same way that a line divides a picture plane. To divide time is to establish its scale—to show it as apparently extending indefinitely in either direction. (Whether or not time has an actual beginning and end can be placed in brackets.) The sound that divides it is like an opaque finitude inscribed at its center.

The tone dividing time divides audio space. There is the space internal to the performance—the space in which tone is related to tone—and the space external to the performance—the space in which the tone is related to the surrounding audio environment. In the open spaces between its iterations, by not being the environment, the tone negatively defines the boundary—here a very porous one—between the performance and what falls outside of it.

In defining the performance’s external relationships this way, the tone points outward to time as a surrounding, infinite field. Just as the zip dividing the field points outward to space as an enfolding state or condition.

Newman’s comments, cited above in the epigraph, were made in the context of a set of reflections on aboriginal earthworks he encountered in the Ohio Valley and his being made aware—paradoxically, perhaps—not of space but of time. What Newman seems to have been getting at is the essentially subjective experience of time, its status as a facet of the world as we take it and as we move about through it.

As hinted at above, there is an extent to which time is, for lack of a better term, private. The sensation of time is a function of our interiority at any given moment or span of moments. In comparison to the time shown on a clock—the time passing from second to second at a uniform rate–the sense of time can be dilated, compressed, uneven, suspended, etc., depending on what we are doing or experiencing. Music that seems not to move, whether by virtue of static harmonies or single long-tone melodies, seems to bring the sense of time to a standstill. Duration becomes something of an image of infinity or eternity until the pause that brings it up short. Hence the function of the pause in reestablishing the sense of scale, of an event taking place against an undifferentiated field. Of raw time.

The length of the tone is judged in relation to the length of the pause. The length of the pause is in turn judged in relation to the length of the tone. An internal relationship of formal elements. These are perceived relative lengths measured by an internal, variable clock rather than the steady intervals of a timepiece. The subjective experience of time expands and contracts with the bowed tone and with the pauses on either side of the tone.

The way we experience the relationship between the tone and the rest between tones is bound up with anticipation. The tone sounding between rests sets up an expectation—a projection forward to a state in which a subsequently sounding tone will make good on this temporary absence of sound.

In the context of the performance, the absence of the tone implies the recurrence of the tone. Anticipation organizes silence as not-yet-sound.

Thus the effectiveness of the performance inheres in reciprocal expectations: That the tone will fill a silence and that the tone will end and reestablish silence. But sound and silence are unevenly matched—the duration of the tone is finite in principle; the duration of the absence of the tone is in principle infinite. Eventually silence will have the last word and the performance will end. Or be suspended for now, to be taken up later.

As an event of finite duration, the bowed tone takes on an allegorical function. We are a finitude within time’s infinite projection into the future; paradoxically, it’s the open nature of the future pulling us forward that anchors a finite existence in time. The bowed tone is metaphorically the carrier wave we ride in that direction.

Until we stop.