Perpetual Ripplets: Henri Michaux

Yuko Otomo

November 2016

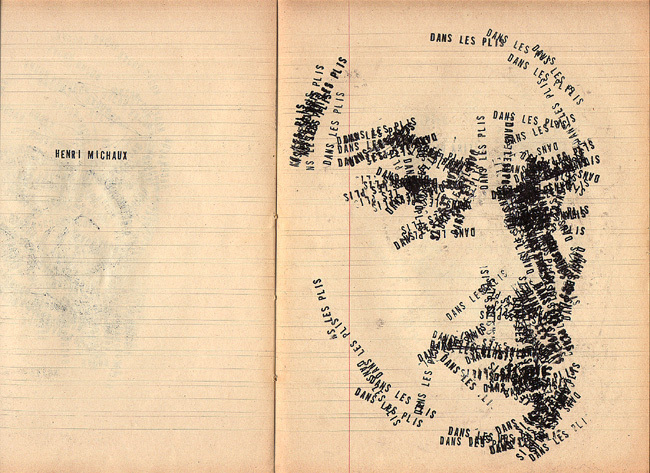

Self-portriat dans les plis

Self-portriat dans les plis

Henri Michaux: Untitled Passages

It was quite a while ago when I first became familiar with Henri Michaux & his work. I was in my mid 20s, going through some early process of affirming my vocation as an abstract painter, when I first encountered his name in Dark Spring by Unica Zürn. In it, there was a segment on his experimental involvement in anagrams. I got particularly enchanted with the idea of anagrams: the alchemy of decomposing, melting, fusing, reconstructing letters & words. The incidental encounter taught me the importance of having an open “flexible” mind. Since then, I have been paying a special attention to his work in either visual or literary contexts whenever I have a chance.

Being born & raised in Japan, where the concept of Furyu-Monji, Non(Un)-Letter, a vital influence of Daoism & Buddhism, is deeply rooted in the thought process of ordinary life, I have naturally learned to live in this world of the logic of “non-linguistics.” Michaux’s unique involvement in this peculiar field of the logic of “non-linguistics” & hieroglyphic writing (especially Chinese characters) has consequently invited me to become extremely curious about his art.

The Drawing Center show, appropriately titled Untitled Passages, starts with Defile de moines ou bein de mandarin (1977 oil/canvas) & ends with a group of drawings done in 1968-76, sandwiching Untitled Passages in between. It is like a Zen circle that starts & ends at the same point. I started my own journey to investigate Michaux’s journey, holding the base of my attention to his chronological development.

In 1920s, awakened to the non-linguistic existence of “illegible marks” (*1) that surpass the semantics of language, Michaux starts his own organic search in art with a full experimental vigor. Becoming aware of the “space within” (*2) & “interior phase” (*3), or interior images, a proof of the multi-dimensionality of our body=mind existence, he follows his passion for a quest. With the most natural attitude, he aims to actualize them on materials. He steps into the world of other dimensions of existence by “derive/drifting” (*4), or floating. He traces the steps & marks of Ki/Chi, a breath of physical/metaphysical psyche of his being. He bravely allows himself to enter the primordial non-lingual world prior to the one based on the logics of language. It is very interesting to see Michaux, who was brought up in the Western world structured with a firm foundation in logos (as “In the beginning, there was word…” in the Bible), being so fascinated by the mysterious chaos prior to logos. I have no clue to find out what drove him to this fascination. Yet, his interest in the Orient is definitely not staying in a mere exotic curiosity but goes further into the more substantial level.

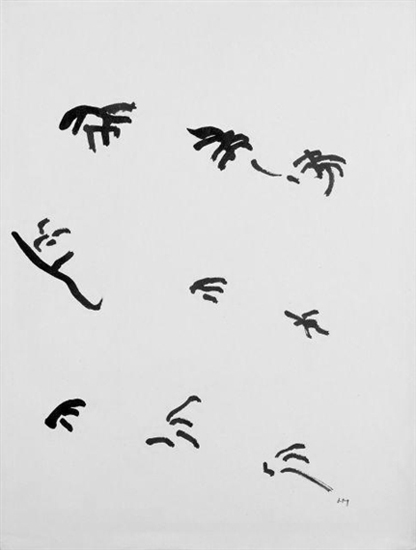

Mouvement, 1950

Mouvement, 1950

1927’s work, Signs Drawings (*4), Alphabet (rerto-verso) & Narration (both done in India ink) shows his curiosity toward shapes of letters & a clear sense of the existence of the hidden world of other dimensions behind them. In this period, Michaux takes a trip to Ecuador in order to have a direct contact with a world other than Western civilization. Typically induced by Surrealism, the series of gouache on black paper done in 1938-39 shows primordial landscapes. They are achieved through the process of jumping into the subliminal world to trace/chronicle the sensation of “being there” directly, rather than through the method of depicting/describing “how the world looks like” then used by most of the Surrealists. These primordial landscapes are drawn with colors & shapes as the pure reaction of his experimental spirit to the time/space he jumped in. Strangely, they are devoid of a self-conscious attempt toward attaining the aesthetics in a general sense. Here, interestingly, we witness his signature establishing its final characteristic form of being “one new alphabet” that combines two alphabets to signify his first name: H & the last name, M, together.

The Untitled Drawings of 1944 show a uniqueness of his voice forming in “lines,” as if they came into being after human figures & letters were decomposed separately & then fused themselves afresh into one. The compositional structure of the plane still shows the basics of a landscape with a horizontal line separating so-called “heaven’ & “earth.” Yet, what is interesting here is the evidence of the fact that Michaux is clearly learning the Surrealist methodology of automatism as his own tool of investigation. There is a definite gap between just understanding automatism as an idea or a concept & learning how to use it as your own actual creative tool. Beside Michaux, among the other few who successfully managed to make it a creative tool, I naturally think of Pollock. In order to understand the connection between “a visual sensory” & “the hand” as a key thread to bind the mental & physiological, physical & metaphysical existence of our beings & to grasp both ends accurately, you have to let your consciousness be together with the breath of mind=body existence & flow with it. Doing so, we are allowed to enter the world of which he calls “space within.” Being able to cross two ends, sensing the demands of the hand or to sense what the hand wants to “see,” we can activate the concept of automatism as an actual creative process.

Our consciousness, especially the one that acknowledges the first layer of phenomenal reality is shallow but quite stubborn. Only when you are able to let this consciousness slightly loosen or withdrawn from the forefront of your mind, you can let your “being” dictate by the movement of the hand in the subconscious level void. There, you are able to capture every aspect of the creative phenomenon with the clearly awakened pure consciousness. Automatism can be under “control” as a creative process only when a dissolved consciousness of the moment or dissolved layers of consciousness are activated in each independent form. Pollock, in his own words, explains this process simply & well – “… When I an in my painting, I am not aware of what I’m doing. It’s only after a sort of getting acquainted period that I see what I have been about. I have no fears about making changes, destroying the images, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise, there is pure harmony, an easy give & take, & the painting comes out well…” In the same manner a pianist practices his/her piano fingers, Michaux tries to master the instrument of automatism. Automatism is a fundamental instrument in practicing the art of painting for me as well; & reaching the “space within/interior phase” is also one of my main purposes in my practice of the art of painting.

Looking at the hieroglyphic aspect of Untitled Alphabet (ink on paper), I suddenly remember that Michaux is also a writer before anything else. It won’t be too exaggerated to assume that his curiosity toward letters & their shapes & forms have derived from the double identities of him being a writer & an artist. Paper, ink & pens, & then brushes join. Just like Victor Hugo, he uses the writer’s writing tools as the artist’s creative tools. With brushes, tools that give more fluidity compared to pens, his search/quest shows a freer & more expansive breath. In his case, the picture plane is his laboratory & the result of his experimentation becomes his “work”. Michaux’s experimental process differs fundamentally from the typical creative process with the mind set to make a so-called “work of art” as its end purpose.

In 1958, as in some of Untitled Drawings (Les Trois Soleils), enlarged sizes of the picture plane & spatial expansion give his experiment freer senses & qualities of improvisation & movement. Other drawings done in the same year also show a similar suppleness. Some of the Untitled Drawings done in 1959 (India ink, gouache on paper) reflect the horizontal movement of his mind=body. It is interesting to witness red & black showing confrontational qualities of male/female, ying/yang. Through his experimentation over a quest to trace “interior phase” in “space within,” he achieves making his direction firmer & its depth deeper. In 1961, the space gets denser than ever before, showing his senses in an all-over format surpassing our typical space consciousness of up/down/right/left. As if looking at the same space from a different dimensional level or an angle, or burying his consciousness in the void/space itself to let it roam there, he clearly demonstrates the fact that he has entered into brand new territory.

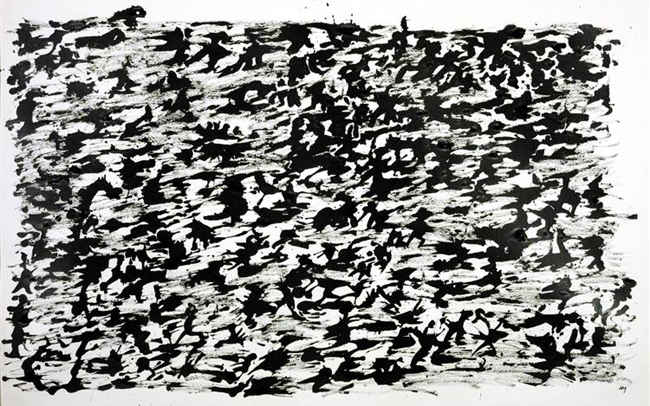

Acknowledging that Pollock had already gone through his (r)evolution of consciousness in breaking through to the territory of the “all-over” in 1960-61, I wonder “who preceded whom” in the creation of this new format. In Michaux’s case, just like Pollock’s, a new form or a style is a result that has emerged from the evolution of a creative process firmly based on inner necessities. They are not some tricks manipulated by an idea alone for the sake of inventing a new style or a form. It happened as a natural phenomenon. Trying not to fall into my curiosity in the sense of a comparative art historical viewpoint, I continue my journey. Some untitled works manifest a dark energy akin to a violent storm of his psyche more than ever in this period. In 1962, overlapping with his interest & curiosity in China, Peinture a l’encre de China (India ink, sepia on paper) shows “illegible” traces of psyche that look something like decomposed human-body-shaped hieroglyphic Chinese letters.

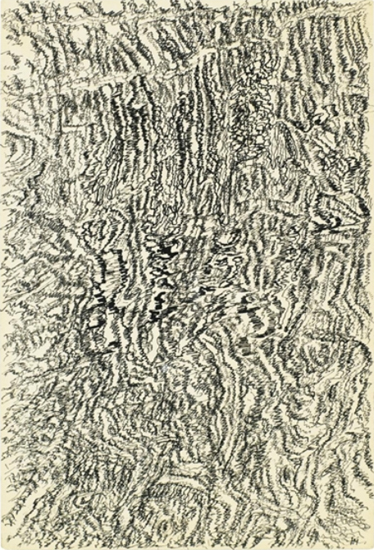

Dessin Mescalinien, 1958

Dessin Mescalinien, 1958

And now, I am facing the Mescaline Drawings on the main back wall of the center. I pay the most & highest attention to this phase of his endeavor. In this show, these drawings have no information panels attached to explain the dates, so, I wouldn’t know their chronology unless I check the prepared catalogue. The fascinating results of experimentation done by a writer/artist with a writer & an artist’s most basic tool, pencils, arouse my curiosity. They give me an intense empathy & a shock that are similar to the one I got when I was first exposed to his experimentation with anagrams way back. How rare it is for a work of art that does not aim at the sensory purpose of aesthetics to induce such a heavy unspeakable “sensory” impact! Michaux’s work, like Pollock’s, is an end result of the search/quest in the most private realm of his world materialized. Through his work that goes beyond the sense of mere aesthetics, we are allowed to step into the mystery of human existence itself. These Mescaline Drawings, unlike Cocteau’s opium drawings, show the voice of psyche merged with the sensation of the moment when paper, a laboratory table & a pencil, a laboratory tool touched each other. In Cocteau’s case, his curiosities toward depicting the subject run much too fast on the forefront. As a result, lines become mechanical & non-organic mainly because they are heavily controlled by consciousness. I myself too have in the past gone through this Cocteau phase.

Michaux’s Mescaline Drawings exhibit a type of a non-image-image; something like traces of a skeletal shadow of the blood flow in his body=mind existence made visible by his unique method of the organic merging of the materials (paper & a pencil) & his psyche. One of the most powerful methodologies of our cognition tool, “letter(s),” dissolved & changed themselves to become a “picture.” Michaux, using the mind-altering drug mescaline, tries to free himself from the world of logics based on the linguistic thought process. He tries to escape from it, responding to the “illegible marks” that are literally “valueless” in a cognition purpose. His self-induced new sense of self-existence & freedom records its own extremely minute reality of the phenomenon showing something akin to the blood of vegetation or micro-cell-like voice of a physical/metaphysical forest. Here, all the residues of traces of human figures that unfortunately have appeared in most of his works up till now no matter what get cleared out totally. As a result, we witness traces of something completely “purposeless.” These trembling voices somehow remind me of Hagiwara Sakutaro’s poem: Take (Bamboo) (*5). Unabashedly, I hoist my voice saying “How Beautiful they are!” clearly but silently inside me. In a pure state of fascination, I keep looking at the Mescaline Drawings: a meaning of a non-meaning freed from the bondage of a typical human frame of mind of cognition as much as possible. It is mesmerizing to witness that a mere record of the passing of time in experimentation that has nothing to do with the concept of beauty has ended up creating such a “beautiful” work as a result.

Away from Mescaline Drawings, I go back to Cinq lignes d’ecriture horizontale of 1961 & more untitled drawings. The experiment of using canvas as the ground instead of paper, a new idea of ink wash… Michaux’s journey continues. Yet, no matter what, except in Mescaline Drawings, in most of the other drawings, some type of figure elements relating to human body images float up as if to tell us the difficulty of freeing one’s mind from the images of the figure, shape & form of human bodies. How strongly we are tied up to a worldly desire to read ‘”something” in simple handwritings: traces of pen movements! Clearly being aware of the problem, Michaux struggles. Our consciousness’ obsessive attachment to our own “physical” human figure is amazingly stubborn. Interestingly & appropriately, the Bible talks of the birth of the original man Adam in the familiar words: “God created man modeled on his own image” (*although paradoxically “Man created God modeled in his own image” could be better said in my opinion). It is very difficult for a normal state of mind to reach the state of pure “illegibility” that happened in Mescaline Drawings to accept the results “as they are” without giving them so-called “legitimate” meanings or relating them to some sort of familiar images that we acknowledge.

Untitled Chinese Ink Drawing, 1961

Untitled Chinese Ink Drawing, 1961

In 1963-1966, the experiments of Ecriture (ink on paper) continue. Simultaneously, Peintere a l’encre de chine (1962) & other untitled drawings show his deepened curiosity regarding China, especially Chinese written characters. For a Westerner who grows up with so-called non-hieroglyphic alphabets, Chinese characters, coming from a completely different phenomenal origin to demonstrate visual symbolic elements, become a grand mystery. Michaux, without slowing the pace of his quest or changing its direction, keeps recording the traces of the “unknown” world. In 1975, in a series of untitled works, we see a new sense of space quite different from the one he used to have. At the same time, the size of his laboratory space, the picture plane gets more expansive. Two untitled works of the 1976 show the new intensity in the flow of his psyche. They, looking almost like a diptych, show an actualization of ying & yang phenomena because of the contrasting usage of black & white.

Michaux, being aware of the energy level & the direction of Ki/Chi, remarkably manages to establish the formula of Ki/Chi=Life Force Phenomenon=Picture(s) that is activated in his work. Here, I think of Brice Marden, whose work comes up to my mind on & off whenever confronted with Michaux’s work for some reason. Most of Western painters, being overly involved with the idea of “subject matter” (“what” to paint), rarely pay enough attention to the existence of Ki/Chi in their work & are usually unaware of it at all. Even Pollock was not totally aware of the fundamentals of bio-metaphysical existence of Ki/Chi in his art, although he himself had such a superbly powerful Ki/Chi dynamic. He was a step before understanding it fully, & I do not hesitate to say that the anxiety caused by this stage of a new awareness killed him. Interestingly, Marden is definitely one of the rare Western artists of our time who is awakened to the philosophy/physiology of Ki/Chi quite accurately. I further investigate Michaux’s world, wondering if Michaux might have influenced Marden, etc. Occasionally, colors jump into his basic black & white world. Further following his work, I take a small note as bellow:

X Pattern(s)

∆ Image(s)

O (Almost) Photographic Depiction of the Interior of Our Psyche

Some late work shows another strong influence of the Chinese calligraphic tradition of “white letters” (*6). His 1974 work Untitled (Par la voie de rythms) reminds me somewhat of work by Norman Lewis. Michaux, even in his late days, walks on his unruffled path without showing any shadow of being “old” or “slowing down.” He keeps breathing vigorously through the theme. “To draw the flow of time,” he claims. Here, appropriately, time means Uji: existence/being=time as in Dogen’s writing (*7) of Buddhism philosophy. It is “existence” itself. “I wanted to draw the consciousness of existence & the flow of time as one takes one’s pulse to communicate with our speed…” he further explains. All through his creative life, Michaux, an artist/a writer, studied, learned & made efforts to understand a “complex equilibrium of a skillful & constant balance between impulses” (*8) to prove a capacity of the visualization of human existence in one of the purest visual forms possible.

PS:

(*1), (*2), (*3), (*4) & (*8) are descriptions written by the curators of the exhibition found on the wall panels in the exhibition space.

(*5) Hagiwara Sakutaro (1889 – 1942). One of the most influential Japanese poets who initiated the colloquial free verse movement.

(*6) Letters in white with black background, instead of the usual setting of black letters in white background.

(*7) Dogen (1200-1253). A Zen Buddhism Master of Kamakura Period. A founder of Soto-sect. The author of “Shobo-Genzo”: one of the most important Buddhist philosophy books ever written.

PS2:

Did Ezra Pound’s Cantos influence Michaux’s curiosity regarding Chinese characters? It is fascinating to see his practice of writing some Chinese characters in his 1969 notebooks similar to what Pound did in his Cantos.

The above writing was done in December 2000 as I enjoyed the exhibition in the Drawing Center NYC. It’s been buried amongst the piles of other unpublished work till very recently. Digging up an old piece to re-read always makes you open up your senses wider & deeper to see things a bit off-kilter in a refreshing way. It’s like looking at the “perpetual ripplets” caused by a pebble thrown into the water longtime ago, bemused. More than 15 years have passed since then & I am familiar with Michaux’s world in a much more solidified manner now. Going through the writing, I enjoy retracing my reactions to this amazing exhibition that took place in Soho when Soho was still an actively creative environment, not the commercialized tourist trap we have now. The Drawing Center is still there at the same location. It’s one of the rare art institutions that has survived despite the absurd changes in the area. We miss the old days when we used to go see this type of art casually as we lived our everyday life.