Perpetual Ripplets: Mondrian 1917

Yuko Otomo

May 2017

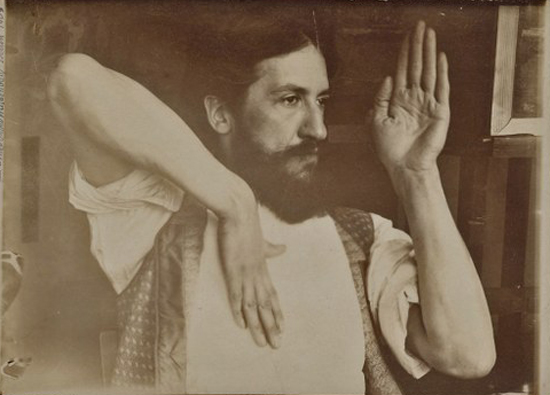

Mondrian practicing yoga, 1909, photo by Alfred Waldenburg

Mondrian practicing yoga, 1909, photo by Alfred Waldenburg

1917

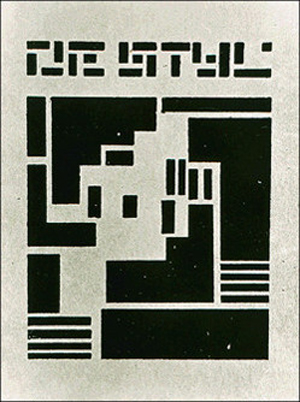

One hundred years ago, in May 1917, Mondrian completed over 200 pages of The New Plastic in Painting (De Nieuwe Beelding in de schilderkunst). He began writing it in the summer of 1914 & kept working on it through 1915 & 1916 in Laren, the village outside of Amsterdam throughout WWI. He finally finished the main part, without the introduction, of his soon to be published first writing in the first issue of De Stijl in October 1917. The entire writing was published as a series of 12 installments throughout the journal’s inauguratal year from October 1917 to October 1918.

1917! It was a year of revolution(s)! The Russian October Revolution took place. Marcel Duchamp exhibited Fountain. Picabia published the first issue of Dada periodical 391. In Japan, the publication of Hagiwara Sakutaro’s Howling at the Moon paved the way for modern Japanese poetry & changed its scope forever. Steiglitz took the photograph The Last Days of 291. Matisse created The Music Lesson. As Degas & Rodin passed, Leonora Carrington, Jacob Lawrence, Robert Lowell, Thelonious Monk & my father were born. In the same year, Einstein published his first paper on cosmology, which would eventually become his theory of relativity. As the end of the 2nd decade neared, the world was moving further into the newness of this 20th century.

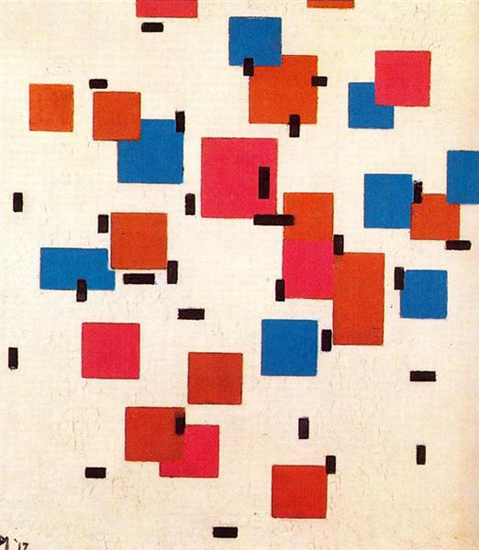

Mondrian’s search for new art was also taking its own course of development, theoretically & also in practice. His ideas had firmly concretized as his creations were able to demonstrate his philosophy simultaneously & vividly. The completion of The New Plastic in Painting coincided with the creation of his two Compositions in Color A & B. His life during the war was not easy, as he wrote to critic & collector H. P. Bremmer in January 1917. He was engaged in “a triple labor”: copying museum paintings, as well as his earlier representational works, in order to survive; pushing forward his latest artistic research; working nights to complete his book.

This line above in italics is a direct excerpt from the book The New Art, The New Life: The Collected Writing of Piet Mondrian (edited & translated by Harry Holtzman & Martine S. James). The edition has a dedication that says “Aux Hommes Futures.” Mondrian originally gave this dedication to his 1920 Neo-Plasticism writing. I love to visualize him writing, all alone at night, delving into his own thought on New Art in a small village while the world was colliding & collapsing with WWI: the war to end all wars. All those breathtakingly beautiful flower paintings of his & the new idea on new art were born out of the shadow of the monstrous first modern war in human history. Now, a century later, the world is in a murky uncertainty of every kind. Socio-politically, creatively & environmentally, humanity is moving toward an unprecedented unknown territory as technology has totally taken over our lives whether we like it or not.

Composition in Color A, 1917, image courtesy of Wikiart

Composition in Color A, 1917, image courtesy of Wikiart

The New Plastic in Painting with the added “Introduction” consists of 7 parts.

1. Introduction

2. The New Plastic as Style

3. The New Plastic as Abstract-Real Painting: Plastic Means and Composition

4. The Rationality of the New Plastic

5. From the Natural to the Abstract: From the Indeterminate to the Determinate

6. Conclusion: Nature and Spirit and Female and Male Elements

7. Supplement: The Determinate and the Indeterminate

It seems that the manuscript is constructed clearly with a book in mind.

It starts with this segment in the “Introduction” as below:

The life of modern cultured man is gradually turning away from the natural:

life is becoming more and more abstract.As the natural (the external) becomes more and more “automatic”, we see

life’s interest fixed more and more on the inward. The life of truly modern man is

directed neither toward the material for its own sake nor toward the predominantly

emotional: rather, it takes the form of the autonomous life of the human spirit

becoming conscious.Modern man – although a unity of body, soul, and mind – manifests a

changed consciousness: all expressions of life assume a different appearance, a more

determinate abstract appearance.Art too, as the product of a new duality in man, is cultivated outwardness

and of a deeper, more conscious inwardness. As pure creation of the human spirit,

art is expressed as pure aesthetic creation manifested in abstract form.The truly modern artist consciously perceives the abstractness of the emotion

of beauty: he consciously recognizes aesthetic emotion as cosmic, universal. This

conscious recognition results in an abstract plastic – limits him to the purely

universal.That is why the new art cannot be manifested as (naturalistic) concrete

representation, which always directs attention more or less to particular form even

when universal vision is present – or in any case conceals the universal within itself.

& ends with this one in “Supplement: The Determinate and the Indeterminate” as below:

Art had to free its plastic expression of the indeterminate (the natural), in

order to achieve pure plastic expression of the determinate. Passing through Cubism,

this was finally seen and felt by the sensitive observer: it becomes clarified to him

through logical thinking. It becomes convincing in practice whenever one compares

the New Plastic with the other painting.Comparison is the standard that every artist consciously or unconsciously

uses and that shows him how to express (his) truth as determinately as possible. He

compares each new work with previous one in his own production or in that of

others. He compares it with nature – as well as with other art. To make comparison

is to exercise one’s vision and compare the basic oppositions: the individual and the

universal. From a clearer and clearer perception of the relationship between this

duality, a purer and purer mode of expression emerges. And so it is logical that

the New Plastic arose.

(*italics by Mondrian)

It is said that the Dutch verb “beeldend” and substansive “beelding” signify form-giving, creation, and, by extension, image. The English “plastic” & the French “plastique” come from the Greek “plassein,” to mold or to form, & they do not really encompass the creative and structural significations of “beelding.” The Japanese term “kaso-sei” is a direct translation of the French & the English. In a strict sense, the original meaning Mondrian meant was not really conveyed to us, unfortunately, because of the language barrier. I’d like to take the word “beelding,” as Mondrian originally meant it, as “form- giving” because it makes the most natural sense.

Coming back to our time, questions & arguments over the meaning of the words: “abstract” & “abstraction” never seem to cease. The terminology, the concept & the practice of “abstract” & “abstraction” have become more & more confusing as time goes by. As the idea & the terms have been consumed by journalism & mass-education systems, its original meaning has been lost to unclear understandings of the term & concept. What is abstraction? What makes abstraction? Arguments go on while the stylized, skeletal & superficial mannerisms of a new kind of genre painting has become the common emblem for abstract art.

Being aware of the realty we face, I pulled The New Art, The New Life: The Collected Writing of Piet Mondrian out of the bookshelf & started to re-read De Nieuwe Beelding in de schilderkunst, trying not to fall into the mistranslation of the term “Beelding” as “Plastic” so as to maintain its original meaning as “Form-Giving.”

On “Why He Writes” in His Own Words

Although the new plastic in painting reveals itself only through the actual

work – needs no explanation in words – nevertheless much concerning the new

plastic can be expressed directly in words and clarified by reasoning.Although the spontaneous expression of intuition that is realized in the work

of art (i.e., its spiritual content) can be interpreted only by verbal art (see

introduction), there is also the word without art: reasoning, logical explanation,

through which the rationality of an art can be shown.This makes it possible for the contemporary artist to speak about his own art.

At present, the new plastic is still so new and unfamiliar that the artist

himself is compelled to speak about it. Later, the philosopher, the scientist, the

theologian, or others will if possible complement and perfect his words. At present

this way of working is perfectly clear only to those who evolved it through practice.

While it is growing and maturing the new will speak for itself, must remain

self-explanatory – but the layman is justified in asking for an immediate explanation

of the new art, and it is logical for the artist, after creating the new art, to try to

become conscious of it.(*italics by Mondrian)

(excepts from 4. The Rationality of the New Plastic in The New Plastic in Painting)

2017

In fall 1995, a major retrospective of Mondrian took place at MoMA in NYC, Piet Mondrian: 1872 – 1944. I visited the museum on Oct. 30 & wrote about it in Japanese on Nov. 6 – 7. I wrote a detailed reaction to every room of the show from Room 1 to Room 13. Then, later in Feb. 1996, I had a revelation on “Tragedy” relating to Mondrian’s ideas while listening to a William Parker bass solo. Listening to him play, I was finally able to untangle my thoughts on the subject & wrote an essay on it in Japanese.

Commemorating the centenary of his first writing on “new” art, I’d like to translate them to make a small series to post as my new Perpetual Ripplets. I’m dedicating this project to Mondrian, the artist himself, one of my mentors who investigated the equilibrium: the unity of the universal & the individual; the male & the female; the inwardness & the outwardness; the spirit & the matter in search of a finer, subtler and more balanced healthier human existence. Now, it is May, a century later, in 2017. It is a perfect moment for me to start a tribute to an artist who painted to actualize its Utopian possibilities.

Mondrian: A Study-De Stijl-First Cover-1917

Mondrian: A Study-De Stijl-First Cover-1917