s w i f t s & s l o w s: a quarterly of crisscrossings

Possibility Itself

Robert Streicher & Daniel Barbiero

←back or next→

tunbridge mtn

tunbridge mtn

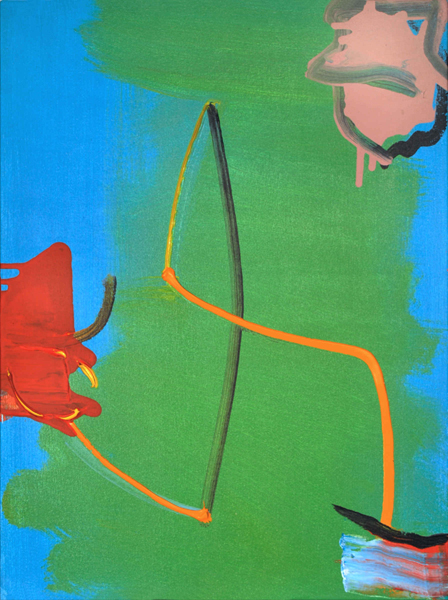

As the sign of the gesture that put it there, the mark raises the possibility that that same gesture could have represented some object or event in the world. A mountain in Vermont, say. This possibility is refused, for whatever reason. And yet the mark as the sign of possibility refused is the mark as, paradoxically, the sign of possibility itself. The constitutive fact of possibility is not the prospect of its being realized but, on the contrary, the prospect of its not being realized. The possible as such is only so to the extent that it does not have to be. The failure or refusal of the mark to represent in the ordinary sense turns the mark back in on itself and discloses it as a sign of the possibility of ordinary representation.

Subject is the conditions of its making. The mark is the trace of a gesture: of the arm in motion, the hand holding the brush, its hairs sweeping across the surface, short waves and thin. Cylindrical paint lines directly squeezed onto the surface. What might be thought of as the gesture’s natural sign: the mark represents the moment of its own creation. To paraphrase the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, we could say that the painted mark on the canvas doesn’t stand for any objective referent existing in the world outside the canvas but rather stands for standing-for itself. Nothing is represented here in the ordinary sense, in other words, but what is represented is the gesture of representing.

Its referent is plainly visible, an after-the-fact consequence of the gesture. An artifact of the imagination interpreting a trace, an entirely accidental effect of a throw of the hand. An oddly-shaped splotch, an upward curving horn jutting from a forehead. A nose and an outthrust chin. An object of pure contingency, something that could very well have been something else had the hand traced a different motion and consequently, had the paint landed in a different way. Not having to be is the mark of its being-as-accident, and hence of the freedom it signifies. The image itself isn’t free—it has no agency. But if we consider that its contingency—its not-having-to-be—is an implication of human agency, we can see it come to stand as a sign or surrogate for human freedom, which is itself an effect of the role—the role of an open determination—that possibility plays in human existence. This devil’s head was possible only once and did not even have to exist at all; that constitutes it as a sign of freedom: the painter’s freedom.

←back or next→

Paintings: Robert Streicher. Prose: Daniel Barbiero

Robert Streicher comes out of the vital New York Dance scene in the 70’s and 80’s, Mr. Streicher took his place as a seminal dance figure when he moved away from the reductive monochromaticism (so pervasive at the time) and into a new renaissance of narration. Streicher turned to paint in the later 90’s, and has proceeded experimentally with his postmodern hybrid canvases with the same authentic voice, which had marked his innovative choreography.

www.robertstreicher.comDaniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His most recent release is Wooden Mirrors, with Cristiano Bocci.