Red Dots and the Signing of Artworks

Sandy Kinnee

October 2020

Some art historians point to Gislebertus as the instigator of the practice of artists marking their own creations when he chiseled “Gislebertus Made This” in stone. Maybe the marking began as a way of saying, “I got paid for making this.” Since then the concept of signing artworks has become a claim of genius, originality, or branding. In recent times it has been pointed out by historians that Gislebertus may not have been an artist or an architect. It matters not. Long before, Greeks and Romans signed their art and there were significant cults of personality associated with artists and architects. But it is Gislebertus who gets the nod anyway. The appearance of a carved chunk of marble below the tympanum of a Romanesque church at Autun is credited with beginning a trend. Artists have since marked the completion of their art by signing it. Over the millennium since Gislebertus’s name appeared, it became general practice for the artist to sign a drawing, painting, or print on the lower, right hand side. Sometimes the artist might write his or her first name and last.

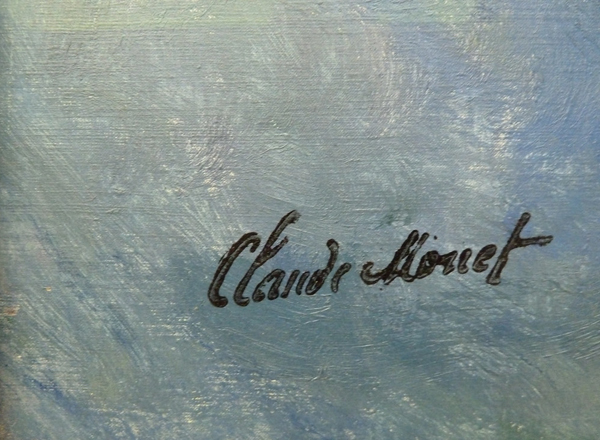

Claude Monet is a classic example of how, why, and when an artist signs or does not sign an artwork. We know Monet as Monet. That single name conjures colors and images. You do not need the addition of his first name to know his work. Yet, early on he needed to use his first name. At the end of his life there were those paintings in his studio that he had signed and many he had not. Those he had signed were finished and intended to go to his dealer for exhibition and sale. Unsigned artworks in his studio were legion. The unsigned works fell into two categories: the artworks he kept for himself, and those that he had not finished. In both cases, the lack of a signature meant the paintings could not be considered taxable inventory. A signed painting was taxable, every bit as any other non-perishable commodity, such as a bar of gold. Why pay tax on a painting that has no immediate prospect of creating income? Monet was wise. Upon his death, his estate executors showed themselves to be similarly clever. They had a set of rubber stamps made based upon Monet’s signature. One stamp would be used on large paintings to add a signature, and thus turn an object into a finished, i.e., signed commodity. A smaller stamp did likewise for less grand pieces. No longer an assertion of identity, a signature was now a prerequisite for monetary worth. The artwork by itself, without a signature, could no longer attest to its own value.

The desire and eventual requirement to sign artworks created fresh problems: the need to know not only why an object was produced but also to establish the identity of an individual creator. Who is this person? Prior to the advent of signed artworks, an object would be appreciated and judged on its own physical merits. In a sense, viewing was a “blind” test. When the identity of an individual is revealed, outside issues can enter to taint the judgment.

It did not occur to me there were valid cultural reasons why my aunt, during the 1940s, signed her paintings: M.E. O’Hare.

It was not a puzzlement; I had just not thought about it. A last name is gender neutral, an initial, standing for a first or middle name, is also neutral. Otherwise, if she signed Mary Elizabeth O’Hare the viewer would look at the painting and know her gender. It took a degree of confidence to sign Mary O’Hare. Yes, confidence because, as silly as it may seem, there was and sometimes still is a bias against art not produced by white men. Everyone knows women first wrote under masculine pseudonyms and then, with recent examples as striking as J.K. Rowling, used initials to avoid being seen as “women authors”. Art made by white men got into museums and was valued more highly. Value in art is another issue of great complexity and fluidity.

As my aunt was a professional fine artist, she was my role model. I was ignorant of what it had been like for her to have a life in the art world. I did know that her work was not sold in art galleries, but it is only in retrospect that I began to consider why and how she survived as a non-gallery artist. Perhaps there were not so many galleries selling the art of women artists in the mid Twentieth century. Or maybe she was doing well enough with commissions and portraits that she did not need gallery representation. Possibly she did not like the idea of producing an artwork and letting a gallerist take a big cut of the sale. Still, I imagine in those early days of her career that she did consider working with a gallery. Such a thing would suggest why, in the 1940s, she chose to sign her work with her initials. Who would buy the work of a woman? Any need to withhold her female identity faded away as her portrait commissions and direct sales increased. Her patrons knew her and there was no excuse to hide behind a pair of initials.

As a kid, without knowing the gender politics behind my aunt’s approach to signing her artwork, I signed my work in a conventional manner: F.A. Kinnee. That did not last long. Soon enough I began signing Sandy Kinnee on my artwork. Eventually I kept the signature but moved it to the reverse of the work where no one could see it at all.

Why I began signing the artworks on the back was a direct result of working in art museums. As an undergraduate I began working in the University of Michigan Art Museum, as an art handler and installations specialist. One of my tasks was to position labels for each artwork. The labels were intended to be informational and unobtrusive. They were not discursive and educational, simply a list of name, date, title, and accession number. Many of the artworks had visible signatures on the lower right corner, but not all. In some cases the artist signed the work unobtrusively so as not to interfere with the artwork’s content.

After completing an exhibition I would observe how visitors experienced the artworks. I found it astounding how many people would, before looking at the art itself, search for the label or signature. Who made this? If the label did not impress them, they might move on to another artwork. If, however, the label did impress them, they might spend more time with the artwork before them. In other words, it was not so much the visual qualities of the artwork but rather the labels and signatures that directed their experience. In many commercial art galleries, years ago, it was also the practice to show the price on the label, which intensified the problem of the label versus the art. A red dot would indicate that the work had sold and was no longer available for purchase. A high price and a red dot might cause a visitor to linger over a painting a bit longer. It was all too common for a gallery visitor to look first at the label for non-aesthetic markers.

In other words, viewers were often using labels and identification as the key to their visual cultural experience. I chose to subvert this backward system of value, in which viewers look at price tags and do not see the art. For my own work I would remove the signifiers and the identity. I sign my work on the back.

In the process of rejecting the cult of personality and price, I have inadvertently sidestepped the problem my aunt faced due to gender. Those who do not know me, might see the name Sandy, and not understand that I am yet another white male with artwork in museums…

Other essays by Sandy Kinnee on Arteidolia→