Segers’ Mysterious Landscapes

Christine Hughes

March 2017

The Enclosed Valley, 1625-30

The Enclosed Valley, 1625-30

Image courtesy Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

With everything that has been happening in politics lately, I felt frivolous going uptown to look at art, but because Hercules Segers is an artist whose work I have loved for years I decided I would go.

I am so glad I did.

The Mysterious Landscapes of Hercules Segers is the largest and most comprehensive retrospective of Segers’ prints and paintings ever done. Segers, according to 17th century records, was a prolific artist but very few of his works remain. The Rijksmuseum states there are 183 impressions from 54 plates and 15 paintings total.

There are no remaining plates.

The exhibit at the Metropolitian Museum of Art has 112 prints and paintings on display. This show originated at the Rijksmuseum last October before coming to The MET, where it will be until May 21, 2017.

The Rijksmuseum owns the majority of Segers’ work, 74 prints, 2 oil sketches and 1 painting. Some forty of their prints came from the Amsterdam collector Michiel Hinloopen (1619–1708) who is thought to have acquired them from the artist’s estate after his untimely death. New research by Rijksmuseum experts shed light on Segers’ materials and techniques. They were able to authenticate several paintings and two oil sketches. The museum has created a two volume Catalogue Raisonne Hercules Segers: Painter, Etcher.

The Two Trees (An Alder and an Ash) 1625-30

The Two Trees (An Alder and an Ash) 1625-30

Image courtesy Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Concurrent with the exhibit at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which ended in January, the Rembrandt House did an exhibit called Under the Spell of Hercules Segers: Rembrandt and the Moderns. This show included the print Rembrandt made from the plate of Segers’ print Tobias and the Angel which he acquired after Segers’ death. Rembrandt reworked the plate leaving Segers’ landscape and adding figures to create The Flight into Egypt c.1652. This print is also in the Met’s show. Other artists who claim a Segers influence were Max Ernst, Nicolas de Stael, Jackson Pollack and William de Kooning. There is a catalogue for this show by the same name.

In 2012 the British Museum, who owns the second largest colllection of Segers’ work, had their first exhibit of its holdings. Much of this material had never been displayed before. The size of their collection is due in large part to the material they acquired from John Sheepshanks in 1836. Of the 24 prints in the exhibit 19 were from Sheepshanks’ collection.

Also in 2012, for the Whitney Biennial, Werner Herzog created Hearsay of the Soul, a pilgrimage to the landscape of Hercules Segers, which was not a film but an installation. Herzog projected large images of Segers’ landscapes, which he coupled with music by Dutch musician Ernst Reijseger. Herzog considers Segers the father of modernity and said of his landscapes “They are not landscapes at all; they are states of mind; full of angst, desolation, solitude, a state of dreamlike vision.”

Mountain Valley with a Plateau 1625-30

Mountain Valley with a Plateau 1625-30

Image courtesy Harris Brisbane Dick Fund and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

There is a bit of mystery in the life of Hercules Segers. He was raised by middle class parents who sent him to apprentice with a well known landscape painter, Gilles van Coninxloo. Segers later joined a guild in Haarlem, which at that time was a center for printmaking. Later he married a moneyed woman sixteen years his senior. Then came financial difficulties. He was forced to sell their house to pay debts, and later he is recorded selling 137 paintings, 33 of those were by him. He moved to The Hague where he died shortly afterwards.

Samuel van Hoogstraten wrote a sort of cautionary tale about Segers, whose date and cause of death is as of yet unknown. van Hoogstraten was quite young when he met Segers, who was in his last years of life. van Hoogstraten writes that Segers, who was despondent, drank too much and fell downstairs and died. This very well may be apocryphal. There is speculation that the reason so many prints are unfinished is because of Segers’ untimely death.

Hercules Segers (1589/90-1633/40) was a masterful printer. He was the first to use paper from the orient, some 20 years before Rembrandt. He created a system of using multiple plates to make a print with depth and colors. He invented the technique of “lift-ground” etching. He developed the “in register” printing technique where two plates are used with different images and colors to create one print. He was first to print on rough fabrics such as cotton and linen, which he often tinted first so that many of his prints were a least two toned. He was the first to do what film makers much later called “a day for night.” By changing the color of the paper or fabric ground and altering the colors of the inks, he could have the landscape go from morning in one print, to dusk, to moonlight in another. There is a series of seven at the Museum, The Enclosed Valley, which are stunning to see side by side. Segers also painted on his prints. He rarely used black ink, which was the most common ink to print with, but instead chose green, blue, gray, and sometimes even white or yellow. There are no two prints the same in this show.

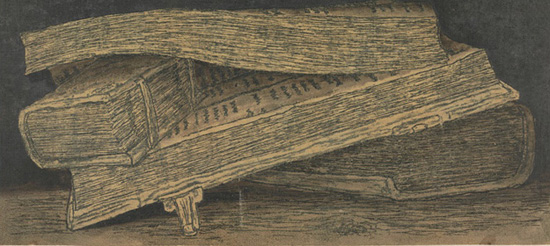

There is a very beautiful print, Still Life with Books, which is said to be the first graphic depiction of a still life.

Still Life with Books 1618-22

Still Life with Books 1618-22

Image courtesy Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The imagery of most of his prints and paintings is landscape. Much has been made of the fact that Segers did not travel, hence did not see the alpine landscape which he sometimes rendered. He saw it from prints only. Also, that he created his own visionary landscapes, usually with a solitary person, a minuscule reminder of humanity or perhaps just to give us a sense of scale. It was unusual for an artist in the “Golden Age” of Dutch painting not to render an accurate version of things with an every leaf on the tree kind of accuracy. He did a scene from his window and added many invented elements.

He was a very capable painter. Rembrandt owned at least eight Segers’ paintings. But his prints for me are where he comes to life. The rhythm in his line is animated. Sometimes his lines aren’t lines at all, but a series of dots and dashes. The richness of line in the lift-ground etchings is very fluid and painterly. The energy in his drawing calls to mind the drawings of some of the Chicago Imagists in that it seems so full of life and so contemporary.

Mountain Valley with Dead Pine Trees 1622-1625

Mountain Valley with Dead Pine Trees 1622-1625

Image courtesy British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Most printmakers are painters first, but Segers used all his skills inventing ways to make and to alter a print. His genius lay here. To see a series of his prints and the variations between them is brilliant. Simon Schama says that Segers’ interest was in “dissolving the distinction between painting and prints.” Segers was not interested in making identical copies of the same image. He also left what most printmakers would call mistakes; acid bitting through a ground, lines hashmarked in otherwise blank areas which, with his skills and knowledge he could have easily repaired if he had wanted. He was experimental.

This is a very rare opportunity to experience so much of Hercules Segers’ work together. It is a world class show and the intimacy of the Levine Galleries is perfect. It is a pleasure to see the galleries full of people. So far it’s not too crowded. It’s about time Segers’ work is appreciated in such a comprehensive way.

Listen to the conversation betweeen Werner Herzog and the

Whitney Biennial co-curators Elisabeth Sussman and Jay Sanders