The Visionary Art of Pablo Amaringo

Tola Brennan

May 2015

Making generalizations about art is tenuous, but to note an exception, it feels prudent to remark on the perceived norm in contemporary art before pointing elsewhere. Visionary or dream states certainly appear from time to time in art movements such as Symbolism or Surrealism, but by and large they’re are an assumed or implied influence. To this observer, it seems that the mid-century saw a decrease in this mode of art-making, instead to be replaced by reflection of material culture, commentary and reaction to historical events, or textually and symbolically manufactured gestures. While a metropolitan turn creates this iteration of fine arts culture, the painter with an easel on the banks of river in the early morning is quaint. Especially in recent times, art is the byproduct of some kind of processing and the artist is a functionary in this creative transformation.

So then what is the contrast? Outsider art and folk art each shift substantially from the more academic process, but perhaps visionary art makes a more coherent gesture. Alex Grey, a well known visionary artist, writes that “The visionary artist creatively expresses her or his personal glimpses of the Divine Imagination.” Grey includes much of ancient art in this category, from the earliest cave paintings to devotional images across the world. Visionary art today is both new and unfamiliar as a genre in fine arts, and arguably the first one. Festival art, notably the installations at Burning Man, also carry some of these influences. There’s also art mediums, and unfortunate forays. But for all the many variations, this is about Pablo Amaringo.

Pablo César Amaringo Shuna (1938-2009) was a Peruvian shaman-turned-painter whose colorful paintings capture the Ayahuasca experience with unprecedented fidelity and creativity. After many years as a vegetalista, he retired in 1977. Amaringo had been developing his painting intermittently since his twenties, but a chance meeting with Dennis McKenna led to the ethnopharmacologist and brother of psychedelic icon Terrence McKenna returning a few years later. In 1985, along with anthropologist Luis Eduardo Luna who encouraged Pablo to focus on his Ayahuasca visions, they arranged for Amaringo’s work to be shown in an exhibition in Switzerland. The international success of his painting brought him the funding to co-found the Usko-Ayar School of Painting along with Luis Eduardo Luna in 1988. Based in Pucallpa and dedicated to the local youth, Amaringo’s school is free of charge and former pupils may eventually become teachers.

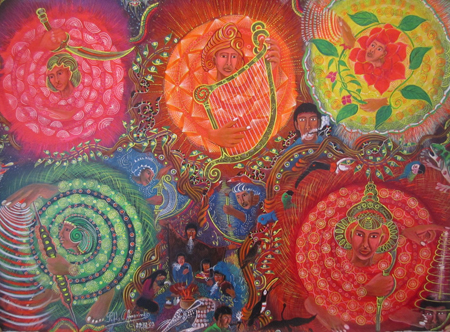

This collaboration with Luis Eduardo Luna spanned many years and resulted in the publication of Ayahuasca Visions: The Religious Iconography of a Peruvian Shaman in 1991. In it, Amaringo’s painting are matched with Luna’s commentaries which detail the context and significance of the imagery. This renowned piece of ethnography and art compilation was a groundbreaking introduction into the visual realms of Ayahuasca and drove many foreigners to seek out the visionary realms of Ayahuasca. Pablo continued to paint and was a frequent lecturer at conferences outside of Peru. After a short struggle with illness, Pablo passed away in 2009. A couple years later, the second major compilation of his work, The Ayahuasca Visions of Pablo Amaringo, was published with contributions from Graham Hancock, Jeremy Narby, Robert Venosa, Dennis McKenna, Stephan Beyer, and Jan Kounen. Also in 2011, his work was shown at the ACA Galleries of New York Shamanic Illuminations: The Art of Pablo Amaringo, Alex Grey and Mieshiel.

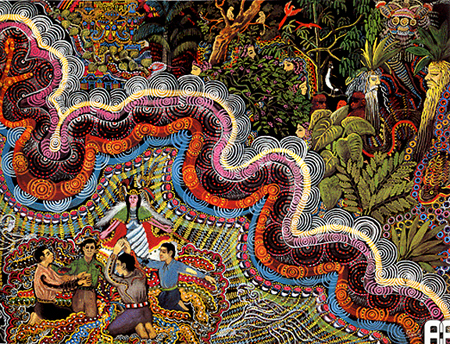

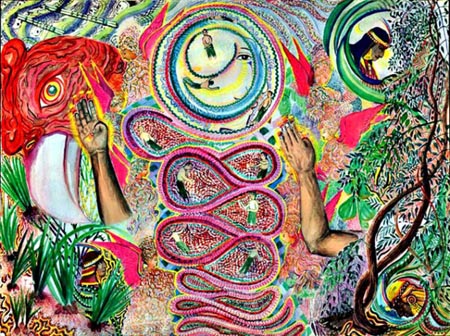

This collection of images gives a good sense of Amaringo’s work and larger set is here. While these majestic works are rich with color and detail, these mysterious and magical scenes take on new meaning when Amaringo describes his process. Longtime supporters Howard G. Charing and Peter Cloudsley conducted interviews with Pablo which were published in Sacred Hoop in the 2006 and 2011 issues. Pablo addressed the understanding of his work saying, “The pictures are a means by which people can cross spiritual boundaries. Some people say they can only believe what they see, but there are things which exist which cannot be seen. The pictures are for reminding people what we are, and where we come from, and where we are going.” These unseen realms populate his works with a wide range of animals, humans, and mythic figures both combining and transforming into each other with backdrops of scintillating patterns and jungle vistas.

Another aspect of Amaringo’s work is it’s clear sense of purpose. He says that “The spirits are working untiringly to protect Mother Nature – everything from the plants and animals to the circles of the planets.” With the Amazon sitting on the front-lines of global capitalism’s quest to destroy the planet, the indigenous struggles to preserve their home certainly informs Pablo’s work. Seeing the beautiful depths of nature in Pablo’s work creates a powerful healing gesture that resonates in a different way than more direct activism. Speaking of the medicinal plants of the rainforest, Pablo shares that “Much of my education I owe to the intelligence of these great teachers. Thus I consider myself to be the ‘representative’ of plants, and for this reason I assert that if they cut down the trees and burn what’s left of the rainforests, it is the same as burning a whole library of books without ever having read them.”

A further point of uniqueness of Pablo’s work is mentioned by Charing and Cloudsley when they write, “Pablo’s paintings are imbued with a supernatural quality, as he regarded them as physically manifested ícaros.” Pablo explains how this works, “I chant ícaros when I paint, so if ever a person wishes to receive teaching or healing, they should cover the painting with a cloth for two or three months. On the day they remove the cover, they should prepare themselves by bathing and meditating. When it is uncovered they will receive the power and knowledge of the ícaros that were sung into it.” These sacred songs are imbued into the paintings, and observing this process shows a special intermingling of sacred ritual objects with fine art objects. The paintings are not simply existing in this physical dimension, they carry meaning, messages and energies from a world yet to be discovered by contemporary art.