Writing Pushed Beyond Writing

Daniel Barbiero

March 2020

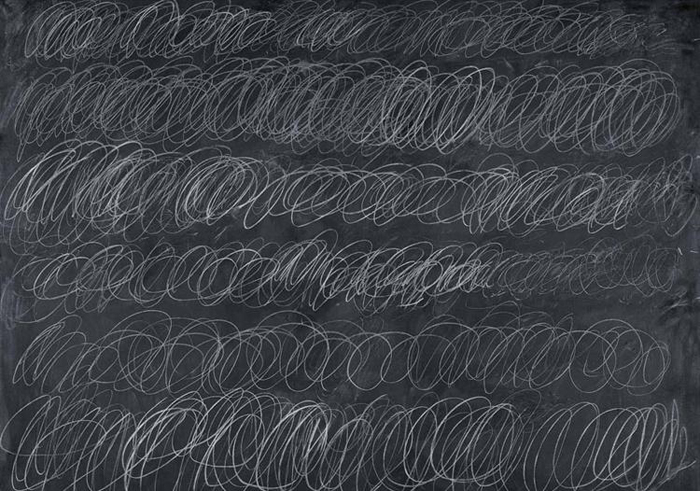

Cy Twombly, Cold Stream, 1966

Cy Twombly, Cold Stream, 1966

The god whose oracle is in Delphi neither indicates clearly nor conceals but gives a sign. – Heraclitus

Since the late 1990s a form of visual poetry consisting in works that resemble, mimic, or otherwise allude to writing systems but that are not in fact examples of any conventionally known writing system, have been much in evidence. These wordless writings–texts or quasi-texts that work outside of systems of ordinary language—qua objects inhabit a unique ontological borderland between writing and visual art. Poet Jim Leftwich in the late 1990s coined the expression “asemic text” to describe these hybrid objects. “Asemic” literally means “without meaning;” asemic texts (or more broadly, compositions) can be further defined as examples of a kind of creative writing that employs linguistic or quasi-linguistic elements or marks—letters, symbols and characters taken from actual or invented writing systems; cursive lines and other gestural marks suggesting handwriting, and so forth—for aesthetic or expressive purposes rather than for communicating messages with a pre-given, author-produced semantic content. The asemic text, in other words, lacks deliberate signification; poet Tim Gaze summed it up neatly when he stated that asemic texts carry no “writer-intended meaning.”

To be sure, works that we would now recognize as asemic texts or compositions had been created years before Leftwich named them as such. The well-known paintings resembling scribbles on a blackboard had been produced by artist Cy Twombly since the 1960s; more ancient roots can be traced back to the illegible calligraphy of Tang Dynasty poet Zhang Xu and the 19th century Zen-inspired calligraphy of no-mind. Another, seemingly unlikely, precursor may be the as-yet undeciphered Voynich Manuscript–if in fact it is the undecipherable hoax or parody many think it is, rather than an actual communication in a secret language.

Because asemic texts mimic some of the salient formal properties of actual, contentful written texts, they are fascinating not only for their appearance—and consequently for their inherent aesthetic value as visual compositions–but for the ways that they engage, by way of negation, questions of meaning and interpretation. Here I will follow the way of negation to see where it leads and to find out what its implications are for meaning and for the very possibility of meaning. Except as it relates directly to these matters, the formal aspect of asemic writing I will leave for consideration for some other time.

The Way of Negation

If asemic compositions mimic the salient formal properties of conventional texts, they do so without containing or conveying meaning in a way that conventional texts ordinarily would. Unlike conventional, semantically encumbered texts, asemic texts refuse to indicate a determinate object, event, idea, action or other extra-linguistic referent. As with abstract paintings, to which they often bear a striking resemblance, asemic compositions’ content is the product of their formal elements and relationships, while their expressive impact consists in the associations those elements and relationships give rise to in the viewer. The formal makeup of an asemic composition may entice us into thinking that we are confronting a message conveyed by real linguistic signs with a semantic function, but when we look more closely we find that these signs are in fact empty ciphers signifying nothing in particular. We can examine them and interrogate them as much as we like, but they can’t be made to divulge secrets they aren’t in fact keeping. Our initial impressions aside, these signs reveal themselves to be quasi-signs that fall into no recognizable, and thus conventionally decodable, linguistic patterns.

And yet their emptiness does signify something after all. Their refusal of semantics—their refusal to have the text refer, based on an author-intended meaning—negatively discloses the semantic dimension of language through its very negation. Negating language’s semantic function serves only to dramatize the fact that referring is one of language’s essential functions: its absence tells us that it is missing because it is something we anticipate will be there, but in fact is not there. In mimicking the forms while vacating the content of writing, the asemic text sets up an obstacle that abruptly jolts us out of our usual expectation—a complacent expectation, as the rudeness of the jolt makes all too clear—that where there is a written text, there necessarily is an intended meaning. The way of negation, in other words, is the way of alienation—of alienating language from its ordinary function of reference.

The asemic composition’s alienation of language comes by way of its illegibility. Illegibility is its fundamental property; it is also the instrument by which it severs the connection between writing as such and writing’s ordinary function of conveying information in the shape of a message we can decode. The asemic composition’s illegibility defamiliarizes writing by forcing attention to turn to the sensual facts on the page—the shapes of the letters and/or other constituent signs, the continuity and rhythms of the line, and so forth. When used as vehicles to transmit meaning, these contingencies of typography or calligraphy ordinarily take on a virtual invisibility, as the meaning of the message acts like a kind of solvent that erodes the sensual facts of writing and leaves behind nothing but itself. (Thus the way of negation is also the way of de-dissolution, as the absence of meaning allows the sensual facts of language to precipitate back into view.) With meaning subtracted from the writing there is no remainder but these sensual facts, which by virtue of their functionlessness become an alien presence.

“Writing is Taking Place Here”

In its own way, the asemic composition would seem to resemble nothing so much as the philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s account, in Language and Death: the Place of Negativity, of the “pure voice.” Inspired by Augustine and the medieval grammarians, Agamben describes the pure voice as a kind of pure self-presence of language devoid of determinate content: an empty and yet latent demonstration that “language is taking place here” (p. 34), an event that erupts in the moment that the voice sounds and before the question of its meaning arises. The pure voice is more than simply the sound of the voice—it is as well the anticipation of what that sound will signify. The pure voice appears at the moment in which spoken language surges up as a simple self-presence in which a “pure intention to signify…is given…before a determinate event of meaning is produced” (p. 33). The pure voice, in other words, is the event of language itself as embodied in the physical act of speaking. It is an event made known to the speaker through the speaker’s self-presence qua speaker in the act of speaking—not through the content of what is spoken. If we were to describe the phenomenological aspect of the pure voice it would simply be as what it is like to enunciate X, where X is a variable standing for whatever intended meaning is being spoken. The actual value for X—the actual content of what is spoken—does not come into play in the pure voice; rather, the pure voice is the physical presence of spoken language as the “bearer of some [as yet] unknown meaning” (p. 33).

The asemic text, as the physical record of the gestures that left their marks on paper, represents a “pure writing” that serves as the written counterpart of the pure voice. Just as the pure voice, as the physical self-presence of the speaker engaged in the act of speaking, embodies the event of language while parenthesizing and putting out of play the matter of content, so the marks in asemic writing serve as the traces of the self-presence of the writer qua writer in the physical act of writing—before the question of meaning can arise. But because as far as the asemic text is concerned the question of intended meaning is prevented from arising at all, that same text remains at the moment of pure writing—remains, in other words, fixed at that point before the question of meaning arises. To that extent, the asemic composition conveys the simple and immediate message, “writing is taking place here.” As with pure voice, the asemic composition signifies that zero point or nothingness that separates the material vehicle of language from the fixed content it ordinarily carries. In the case of the asemic composition, though, that moment when determinate meaning finally does arise would seem to be perpetually put off.

Lack of intended meaning is to the asemic text what latency is to the pure voice—an emptiness that reveals something that ordinarily would be there or should be there. If the pure voice illuminates a clearing in which meaningful speech will arise, the lack of an intended meaning at the heart of the asemic text is, conversely, like a dark light throwing into sharp relief the fact that ordinary texts do in fact carry an intended meaning. To chase this observation further—to chase it into the area of metaphysics, in fact–the asemic text’s lack of intended meaning corresponds to the unspeakability of ultimate being in neo-Platonic and other ontotheologies of late antiquity. If, as according to these ontotheologies the ultimate ground of being is a nothingness that can only be spoken with the voice of silence, then similarly, the ground of linguistic meaning in the intention-to-mean can be conveyed through its negation. In either case we are confronted by a paradox: what is either unreachable or refused is revealed precisely by virtue of its being unreachable or refused.

The Impossibility of the Asemic & Homo interpretans

But are asemic compositions truly empty of meaning? Are they in fact asemic? From the beginning the name was understood to be paradoxical if not outright contradictory. Leftwich, in a 27 January 1998 letter to Gaze, acknowledged that “[a]n asemic text…might be involved with units of language for reasons other than that of producing meaning [and thus] would seem to be an ideal, an impossibility, but possibly worth pursuing for just that reason.” By 2011 Leftwich refined his initial insight to include the caveat that “there is no such thing as asemic anything. everything is readable, i.e., can be and will be given meaning.”

The impossibility of the asemic is in fact an appropriate point of departure. The intuition that that realization encapsulates is that meaning must always be made present, particularly in texts and other objects that appear as ordered collections of signs of whatever sort. Meaning doesn’t vacate the locus of the sign any more than we can abandon the possibility of meaning in anything that, whether designated specifically with that function or not, can be interpreted as a sign. We turn to the possibility of meaning—to the idea that this mark here has something to convey to us—almost reflexively. If we naturally take the world to be something that has something to say to us if only we knew how to decrypt its message, then our adopting an interpretive stance toward things in the world—particularly those that have the distinguishing look of signs—will be second nature.

The interpretive stance is natural to us as beings inhabiting a meaning-saturated world. Human being is homo interpretans, the being that interprets, and meaning is always a possibility to a being that is prone to interpret. To homo interpretans text in general, and a quasi-text made up of marks and signs that mimic rather than instantiate a known writing system in particular, are naturally prone to holding out the possibility of meaning, and thus of soliciting interpretation. We might say that, like the Delphic oracle the asemic text neither indicates clearly nor conceals, but instead gives a sign. A sign that it falls to the querant—here, the reader—to perceive and interpret.

Interpretive Stances, Interpretive Criteria

For homo interpretans, the question isn’t whether or not interpretation will take place, but how. If there is a devil hiding here, he is to be found in the details of that how. And there can be many devils, which is to say many modes of interpretive stances one can take, given the type of meaning one expects to find. This latter may be, for example, indicative—denoting or referring to some object, event or idea, real or fictional; expressive—i.e., articulating a psychological state or feeling; performative—i.e., accomplishing something rather than alluding to it or describing it. Our stance toward any one of these types of meaning will reflect the appropriate response to the meaning in question—looking for the truth or accuracy or similitude or self-consistency of the indicative; being affected by the expressive; deriving pleasure from or being moved by the aesthetic, and so on. More generally, if to interpret some text X is to understand X as containing some sort of meaning, then this expected meaning serves as the criterion one uses for choosing an interpretive stance. For conventional texts whose intended meanings can be gleaned from formal features or contextual cues, settling on the appropriate interpretive stance is in principle something that can be done with reasonable confidence. With an asemic text, this confidence breaks down.

While the meaning of even the most conventional text will be marked by some degree of ambiguity or indeterminacy, the type of meaning we expect from it will, at least initially, establish a more-or-less generally understood framework of reference that places certain constraints on what counts as the “right,” or at least plausible, interpretation. But because the asemic text lacks originary meaning, it lacks such an initially graspable framework and attendant set of constraints. To interpret the asemic text is to grasp negatively the very taking place of meaning. The place language opens up for meaning is, in the asemic text, indicated by the effective absence of intended meaning, thus making of that place a vacancy; absence of meaning functions as a placeholder or a sign reading “here (would) be meaning.” Interpretation must somehow fill that vacancy, but in order that it do so, the most appropriate interpretive stance must be taken up.

For a clue to what that stance will be, consider that with no referential content to dominate it, the aesthetic itself in effect becomes the asemic work’s message. It is, in effect, essentially an aesthetic object. And as an aesthetic object the asemic text overflows the category “written text” and spills over into the category to which abstract drawings and paintings are consigned. In fact, Gaze has noted that texts and images exist along a continuum; asemic texts are situated somewhere at the midpoint, where the distinction between the two types of object is obscured or rendered irrelevant. What this means is that the interpretive stance appropriate to the asemic text is similar or identical to the interpretive stance appropriate to an abstract drawing or painting. It is an interpretive stance rooted in the aesthetic sensibility rather than in semantic inquiry; ultimately, interpretation will be imaginative. For it is only a projection of the interpretive imagination that we can construct the web of correspondences and associations that are capable of filling the asemic text’s originary semantic void. It may be helpful to think of this kind of meaning as an emergent property of an asemic composition, which is to say a product or manifestation of the confrontation of the text by the imagination, and not as an independent property in its own right. Simply put, the absence of originary, independent meaning leaves an opening that only the imagination can fill; the imagination will provide its own justification for how it fills that absence, and with what.

From the Asemic to the Polysemic

In confronting a text without an intended, determinate content, interpretation will inevitably be a matter of imaginative flux and metamorphosis—of discovering and rediscovering possible meanings that are always subject to change and motion. This interpretive flux just is a consequence of the way the imagination is. By nature it is plastic and notable for its capacity to generate an almost bewilderingly variety of images and associations through its free play. But it is also a consequence of the text’s lack of semantic fixity, itself the logical result of its having no originary meaning, exerting a weak or elastic constraint on imaginative play. What little constraint it does impose—which, as noted above, is a function of its being interpreted aesthetically–is in any case more likely to be enabling rather than prohibiting.

Given the natural flux of imaginative interpretation, any given interpretation of the text’s meaning will, in principle, find itself liable to being superseded, subsumed and/or replaced by a subsequent interpretation. The search for an endpoint– a final or even a definitive interpretation—will only be frustrated as new interpretations suggest themselves with each new reading of the text. Any given interpretation will arise as simply one moment within a process whose outcome is always open to change. It is an ongoing process in which anything like a final, unequivocal meaning will always be just out of reach, a process of constant approach and withdrawal, a lateral movement away from the possibility of a fixed message or unequivocal set of references and a movement instead toward some unknown X—a variable the value of which interpretation must constantly determine and re-determine for itself. The apt parallel here is to the paradox of Zeno’s Achilles, who can never catch up to the tortoise he’s racing. In the same way, interpretation always nears but never quite meets the meaning of the asemic text—because there is no such meaning to be met. Interpretation, in a sense, is really chasing itself.

This means, among other things, that no interpretation of an asemic text will be wrong. Asemic writing by definition entails a rejection of the truth claims that follow from, or are at least implicit in, referentiality. The asemic text is neither true nor false but simply is a prompt to the imagination. To the extent that it rejects truth claims and calls instead for an ongoing process of imaginative projection, we might say that asemic writing represents a “weakening” of writing—“weakening” here being used to call up a deliberate echo of “il pensiero debole,” or the “weak thought” propounded by philosophers Gianni Vattimo and Pier Aldo Rovatti and others in the 1980s. Weak thought took a perspective that sees our engagement with the world as made up of an ongoing set of interpretations that themselves are based on a history of previous interpretations: experience as interpretation all the way down, in other words, never to arrive at a fixed, unchanging reality transcending all interpretation. Similarly, the asemic text contains no single transcendent meaning to dig down toward and uncover; rather, it is the site of multiple readings and plural meanings that are simply the products of imaginative interpretation.

Thus the asemic text’s indeterminacy of meaning and refusal of reference do not equate to asemia per se (if asemia equals the impossibility of meaning) but instead act as the ground of the possibility of meaning—a possibility that realizes itself concretely as multiple meanings in a state of flux. If meaning is possible by virtue of the asemic text’s negation of a given, determinate meaning, it is a possibility that manifests itself in the—in principle—open-ended plasticity of the projective imagination. This is writing that pushes beyond writing, writing that pushes interpretation into an endless series of moments or events of an inventive flux—a polysemic, rather than asemic, writing.

Quotes from Jim Leftwich and Tim Gaze are from Jim Leftwich, Asemic Writing: Definitions & Contexts: 1998-2016 (Roanoke, VA: TLPress, 2016).

Also referenced: Giorgio Agamben, Language and Death: The Place of Negativity, tr. Karen E. Pinkus with Michael Hardt (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 1991).

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.