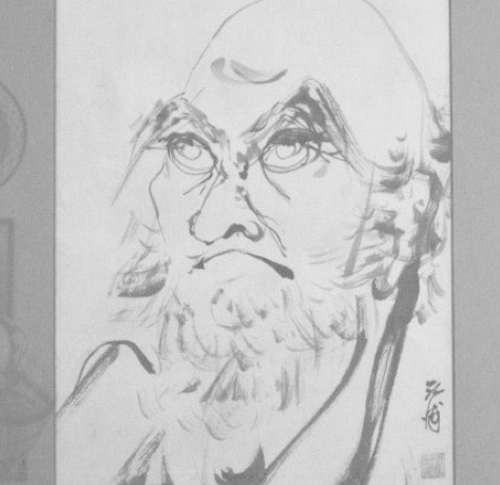

A Portrait of Bodhidharma

Ivan Klein

March 2019

We acquire the portrait of Bodhidharma by our friend and neighbor, the master Japanese brush painter, Koho Yamamoto. A portrait that I admired for years when it hung in her Soho studio.

“The best Bodhidharma I’ve ever seen,” I declared to her at a traditional New Year’s Day get together shortly before the studio closed after a thirty-year run. “Quite a compliment,” she laughed modestly while calling attention to the Indian cast of the portrait’s features.

Found deep in storage and brought to our door by her faithful student and friend, Jaya, who tells me that it does indeed look a bit Indian and for sure she should know.

The basic outline of the Zen origin story seems worth sharing as I look up from my journal at Koho’s painting propped against a bookcase prepared for hanging. It’s the real thing all right – a bowshot down the empty corridor of time from when this terrible old man, the 28th patriarch in a line of direct transmission that began with Gautama, took it in his head sometime in the 5th century of the common era to sail for southern China and spread the authentic doctrine.

Engaged the Emperor Wu in a seminal dialogue. The Emperor, a builder of Buddhist temples and an all around benefactor of the faith, asks the stone-faced teacher what merit his benevolence will accumulate for him in heaven.

— None whatsoever.

— Then what is the nature of the dharmakaya? (lit. the body of the law)

— A vast emptiness with nothing therein.

— Then, who are you?

— I have no idea.

At which point the story has him putting his sandals on his head and walking north. He is supposed to have found a suitable cave and contemplated its rock surface for nine years until importuned by one Hui-Ko to pacify his mind. Roughly shoved outside, Hui-Ko showed his sincerity by cutting off an arm and presenting it to his hoped for savior.

Ok, if it’s going to be like that, whip out this troubled mind of yours, put it on the table and I’ll see what I can do. – Whereupon, Hui-Ko was immediately enlightened and became the second Chinese patriarch in the Chan (Zen) line.

There’s a classic painting of this scene by Sesshū Tōyō inscribed 1496, notable for the striking brushwork of the cave’s textures, Bodhidharma’s dogged wall gaze from under his monk’s hood and the anxious aura around Hui-Ko’s presentation of his severed arm.

The arrival of Koho’s painting takes me away from my current preoccupation with the provenance and metapsychology of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and what might be called the morphology of Jew hatred.

Agony into dust, finally. Maybe just a bit like the dust of the Topaz concentration camp (woke Japanese term) trod by the young girl Masako Yamamoto who produced this marvelously fresh version of Bodhidharma.

Dust surrounded by barbed wire with an American flag flying overhead. Also captured by Koho (the name bestowed by her distinguished teacher, Professor Obata) in her iconic true survivor’s rendition.

She gives us Daruma [Jap.] bald, his head sloping at severe angles front and back. In the center of his forehead a single brilliant brushstroke suggesting the light and darkness of this world and the next. Thickets of triangular eyebrows above wall-gazing eyes. A bit of a beard, a few masterful lines that create a sense of substance to the bust as a whole. A mouth cast downward, but in its set and determination, a humanity as well as severity. – For me, what most crucially sets this portrait apart.

I invite the great artist upstairs to see the painting newly mounted above my desk, and she graciously says she approves of the home it has found. I tell her I will look after it as best I can and pass it on if I am able to someone who will appreciate it for what it truly is. Understanding between us, I’m pretty sure, what in the matter is mere possession and what is transactionally eternal.

◊

Published “Toward Melville,” a book of poems from New Feral Press, in July 2018. Previously published a chapbook “Some Paintings by Koho & A Flower Of My Own” from Sisyphus Press. Work published in the Forward, Urban Graffiti, Otoliths, and numerous other publications.