Afterword

patrick brennan

September 2022

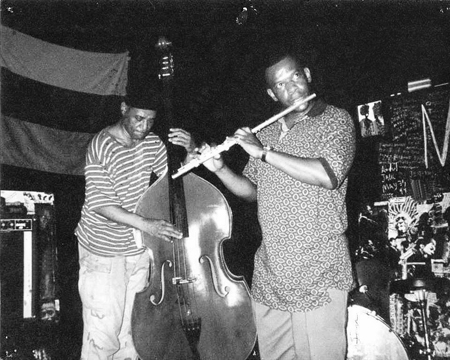

The African Omnidevelopment Space Complex / We New

1972 at the Ibo Cultural Center on 6 Mile Rd. near Woodward Avenue in Detroit, where all were awaiting a burn the house down performance by a McCoy Tyner Quartet that included Sonny Fortune, Alphonse Mouzon and Calvin Hill:

“Hey European Brother.”

I had to do a double take. “Just what is he talking about? European? I’m not European. I don’t get that. Okay, I’m American, okay … but … European?” I was thinking to myself. This wonderful, open hearted, generous person, had just sat down next to me and introduced himself as Ubadiah Bey McConner (19937-2020), who eventually came to identify as Ra’maat Ubadah Hotep Ankh McConner Iheru.

Learning that I was an aspiring player, he immediately invited me to come up to a session at his place In Pontiac, an industrial city about 30 miles north of Detroit’s central hub, and initiated a long lasting friendship that grew far closer to family depth than friendly acquaintance.

Being as inexperienced and naive as I was at the time, all of this seemed completely ordinary and natural to me, and it’s the gift of a hindsight that’s been able to perceive the cumulative ripple effect of these experiences that’s allowed me to recognize just how extraordinary Ra’maatubadahhotep’s character, initiatives and achievements really are. In his own words, he has been living from the git-go a “charmed life” — a charmed condition of being that he’s imparted to others whenever possible.

I’d been wondering if any press or scholars had ever documented and recognized the impact of The African Omnidevelopment Space Complex / We New, a home based cultural center that hosted an artist initiated musical situation in Pontiac for 3 decades from the early 70s into 2002, and I’ve come across no more than a short line or two in a small Pontiac paper. I’ve wondered why this has been so and have been considering the filters that so often define “history.”

Conventional histories are, of course, told by those who’ve survived and even more so by those who happen to dominate. The reverse engineering of these “histories” tends to justify a status quo and to selectively construct a narrative that makes a particular version of the present seem inevitable.

In the case of most music histories, star status often decides the price of inclusion. And, just on the say so of succeeding generations of musicians who’ve adopted their influences, it’s hard not to notice the impact of Armstrong, Ellington, Parker, Coleman and Coltrane. But, as the threads of affiliation have grown ever and more complex during the past 5 decades, attention has defaulted more to those who are most recorded, most written about and who manage to get paid to play overseas (and every so often, even right here in Gumboamerica).

Of course, musicians should be paid appropriately and enjoy some recognition, but this default position also instantly assumes that only market oriented career paths may yield “important” music and that the “serious” value of musical process derives only from its sonic product, whereas the reality of music is much more complex than this.

One of the many, many achievements of the A.A.C.M., for example, is that so many of its members both left Chicago and successfully engaged the international music market (and their musics merit that at the least). Although these successes have helped argue some credibility for their music, it still took an association member (and not an outside gatekeeper), George Lewis, to write and publish that group’s history in A Power Stronger than Itself.

But, what about other initiatives that stay local, don’t even leave home and don’t even address market relationships? Do these therefore “not exist” as “real” music? Are they only “amateur,” “folk,” “hobby,” “amusement” or … “therapy?” Imported classifications such as these sidestep and gloss over the actual complexity, range, variety and meaning of musical activity.

Ra’maatubadahhotep, for his part, never waited for any outside permission to do what he wanted to do. He did it, documented it, mythologized and sustained it on his own terms, defining his own social and artistic aesthetics and standards while successfully working them through. He magnetized and thus drew the world in, rather than vice versa, continually keeping the process receptive to new musicians and new generations without preemptively locking into any single phase.

The intensity of his musical dedication and conviction nevertheless also radiated outwards, as musicians from all around the Detroit area were aware of what he was doing, with Faruq Z. Bey, Donald Washington and James Carter being among those who’d come through regularly.

The music has also concretely changed and redirected lives, where some grew into mature musicians. Others discovered alternatives to the undertow of the streets, while the music helped still others live and dream beyond the restrictions of their prison confinement.

I participated in activities at The African Omnidevelopment Space Complex / We New from 1972 till ’75, when I drove with Sadiq, one of the drummers from that scene, to attempt for myself the artist and musician’s life in NYC, and I’ve ever since felt myself an ambassador of the Space Complex. That world travels with me wherever I go.

Ra’maatubadahhotep wholeheartedly accepted and encouraged anyone who came through his door, and this acceptance resonated with such a generosity that people would come to believe it — and even accept themselves more affirmatively in new ways. Such are the spaces he creates. The unconditional conviction with which he played also modeled how to do that oneself — and this is rarer than one might think.

Having since road tested my experiences with The Complex, I can attest to this contagion. When tactical and technical odds against my own artistic aspirations taste especially heavy, I notice that some of the unjustifiable confidence despite apparent evidence that sustains me is not just something I’ve cooked up on my own but draws also on the transcendent belief generated at 92 N. Ardmore. This may not noticeably change the mad, probabilistic world we inhabit, but it can seriously alter what we choose to do with it. I don’t think I’m at all the only participant, visitor or neighbor who’s felt that way either. Just think about that Greek guy Archimedes’ approach: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the earth.”

READ PIERRE CRÉPON’S REVIEW ON THE WIRE →

REVIEW BY DANIEL BARBIERO ON AVANT MUSIC NEWS →