Edgard Varèse and the Jazzmen

Marcelo Bettoni

June 2025

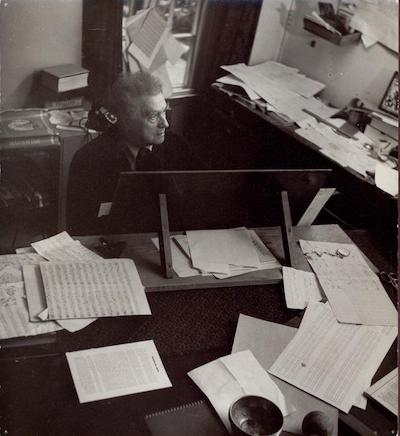

Edgard Varese in his studio in New York City, spring 1957,

Edgard Varese in his studio in New York City, spring 1957,

Courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Edgard Varèse and the Jazzmen:

The Avant-Garde That Anticipated Free Jazz

In the spring of 1957, while the jazz world was undergoing an aesthetic revolution with names like Coltrane, Mingus, and Davis redefining the genre’s boundaries, another event was taking place in the shadows of New York’s Village. One that remained almost secret until recently. In a loft in Lower Manhattan, the French-American composer Edgard Varèse led a series of Sunday musical workshops that included essential figures of modern jazz: Teo Macero, Art Farmer, Charlie Mingus, Hal McKusik, Eddie Bert, Don Butterfield, Frank Rehak, Ed Shaughnessy, Hall Overton, and possibly John La Porta.

This workshop was not only a crossing of worlds but also a unique sonic experiment. The recordings—now preserved by the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel—capture a radical experience that prefigures free jazz, three years before Ornette Coleman’s celebrated Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation. Since his arrival in New York in 1915, Varèse had shown an open ear to urban and popular sounds. His music did not follow European tonal logic; it was an obsessive search for new timbres, open structures, and unconventional rhythmic organization. In that sense, his aesthetic ideal approached the boldest developments of bebop, albeit from a different starting point.

By the mid-1950s, Varèse regularly attended jazz concerts at Village clubs, listening to Coltrane and other experimental musicians. He also maintained a fluid dialogue with Teo Macero—saxophonist and composer who would later become a key producer in Miles Davis’s electric career—and with figures in John Cage’s circle such as Earle Brown and James Tenney. Varèse was not a casual visitor to the jazz world: he observed it attentively, questioned it, and in his 1957 workshops, summoned it.

The rehearsals led by Varèse were unconventional. According to witnesses like Robert Reisner, a jazz journalist, they were a kind of “structured happenings” combining abstract instructions, free improvisation, and manipulation of the sound space. For jazz musicians accustomed to functional harmonic language, the experience was disconcerting but stimulating. The interaction between these worlds produced an indefinable music, halfway between free jazz, musique concrète, and electroacoustic collage.

Varèse’s interest in these musicians went beyond the anecdotal. His conception of sound as physical matter, his use of silence as structure, and his disregard for formal conventions resonated with the sensibility of improvisers beginning to break the limits of hard bop.

An even more symbolically charged story occurred in 1954: Charlie Parker, seeking new sonic horizons, approached Varèse with the intention of studying composition with him. Parker had reached bebop’s expressive ceiling and was looking for new languages. He admired works such as Ionisation and Déserts. But the meeting never took place: Varèse left for Europe, and when he returned to New York in May 1955, Bird had died two months earlier, on March 12. That frustrated dialogue between two geniuses speaking different yet complementary languages is, in itself, a symbol of what could have been a revolutionary collaboration.

Although Varèse never identified as a jazz musician, his legacy reverberates in the genre’s most radical explorations. From Cecil Taylor’s dense textures, through Coltrane’s freedom in Ascension, to the sonic collages produced by Teo Macero for Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, his influence—sometimes direct, sometimes through aesthetic osmosis—is undeniable.

Even his way of working with prerecorded tapes and electronic manipulation in works like Poème électronique anticipates sampling, looping, and collage techniques that would mark both hip hop and 21st-century experimental jazz. The 1957 recordings remained stored away from public release for decades. Today, listening to them is witnessing a transitional moment between two worlds: African American jazz seeking new forms of freedom, and European avant-garde music challenging its own structures.

Beyond genre, those tapes document an unstable and fertile territory, where improvisation becomes sonic architecture, and composition turns into a performative act. There, jazz met the avant-garde—not to merge, but to rehearse a new, still uncodified language.

Edgard Varèse died in 1965. Free jazz was already underway. But his radical gesture, his ability to convene young musicians to rehearse without scores, forms, or safety nets, prefigured many of the quests jazz would undertake thereafter. Sometimes, great intersections leave no work, only gestures. This was one of them: a foundational gesture, recorded on tape, yet still resonating at the boldest edges of contemporary jazz.

◊ ◊ ◊

◊ ◊ ◊

Buenos Aires guitarist & musicologist Marcelo Luis Bettoni is the author of a number of books including El sonido de los modos (The Sound of Modes, Tinta de Luz, 2021), Rítmicas de guitarra (Guitar Rhythms, Tinta de Luz, 2021), and most recently an exhaustive history of jazz, Las Rutas del Jazz (The Roots of Jazz, Publiquemos, 2024).