Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth

Colette Copeland

November 2023

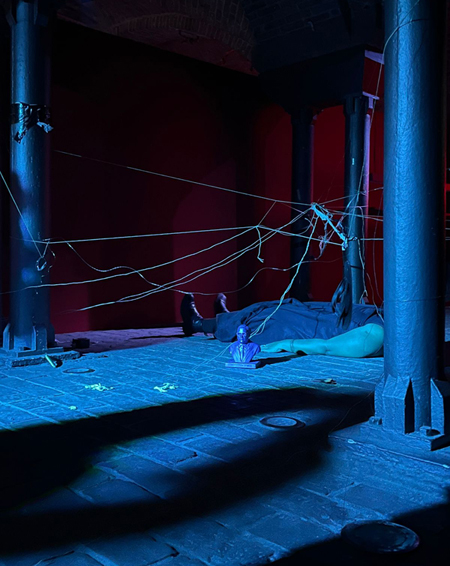

performance still from Body as Caste Field

performance still from Body as Caste Field

I first met Jyotsna Siddharth in an online performance art class taught by Alicia Framis at The Alternative Art School (TAAS). Since that first class, we have been together in two other classes at TAAS and I’ve enjoyed getting to know her work and the scope of her art and activism practice. I recently met her in person in Delhi, India where she resides and was honored to see her perform The Body as Caste Field at Shrine Gallery.

Colette Copeland: Your work takes many different forms–artist, activist, performer, writer, theatre producer…How do the various disciplines intersect and inform one another in your work?

Jyotsna Siddharth: I am fascinated with life and the world; hence my work takes multiforms. I see art as a vessel through which we channelize our deep psyche and emotions. Art for me is a way of life–to create a world and ecosystem from everything I have experienced and not.

My fascination with life, curiosity and listening to my heart has led me to work across multimedia forms such as visual, socially engaged art, performance, theatre, acting and writing. For me, the process of art making and the language of it are the most important values. I am learning to not put as much focus on the outcome, no matter how much it is expected from the artist, as most art institutions in India, as well as globally limit art to objects. The relationship of objects with art is an important one as it brings our ideas forward in a more tangible manner. However, that definition is limiting, as art transgresses the boundaries of objectification. The existing forces of capitalism enmeshed with globalisation and conservative supremist powers see art as a threat. Hence, the commercialised art finds more buyers than the one that is using it as a tool to assert and resist. The work that I make questions the political economy of art making and subverting the existing narratives within but most importantly, existing stereotypes and judgements about artists that come from historically disadvantaged backgrounds.

I have made work that has shaped practices of many artists and organisations in India. When social media picked up on cancel culture, I was writing about mutual accountabilities that brought about a significant shift within feminist discourse, conversations that I have curated or engaged in with several artists and activists particularly in my work with UN agencies. I brought together ten different artists to help us create a pedagogy for the feminist lab that galvanised 30 intersectional feminist youth leaders across India to break the silos between “art” and “activism” for a shared collective vision towards feminist change. I have held several situations and moments of individual and collective dissonance to create safe space for opposing views to exist for a healthy collective dialogue and work.

Another important work that I did was to bring my academic work on caste, love and romantic relationships for larger engagement as a digital project called Project Anticaste Love. This platform was the first digital platform that I created in 2018 to create a public discourse on the interconnections between caste, faith and sexuality in love and relationships. My work was appropriated in 2020 by dominant caste journalists who created a similar platform without any recognition or acknowledgement of my existing work which was widely covered in mainstream news. This enriched my artistic practice as I started a public dialogue on individual proprietorship of marginalised folks in absence of creative commons law in India.

All of this asks for radical feminist work, emotional labour and hardships that I continue to endure in form of silences while navigating blockages and gatekeeping particularly from art institutions that are predominantly run and owned by both dominant castes, cis heteropatriarchal institutions, curators and fellow artists but also anti-caste curators and writers.

CC: As a queer Dalit feminist, your work speaks out against systematic gender and caste oppression. For the Western readers who might not be aware of the caste system or caste discrimination, please speak briefly about how that manifests in India’s current culture.

JS: Caste is both a structure and system that operates through a performance of oppression and violence towards historically oppressed community such as Dalits. Caste system is four tiered where each person born in India and South Asia inherit a caste depending upon which family they are born into. There are primarily four castes and then the Dalits who are located outside that system and are often excommunicated socially, economically and culturally. I come from such a case where my ancestors were involved in cleaning work and hence were excommunicated. It is similar in a way to how race operates where the societal systems and its machinery excludes people on the basis of work, descent, colour and birth. It is different from race, in that it is not as apparent, since you cannot tell if a person is Dalit unless you know about their last name and ancestral lineage of work.

Most Indians who have historically migrated to other countries particularly to the west come from dominant caste locations also known as upper caste, savarna. As they had integrational wealth, assets or money they were able to immigrate to other countries. With that, they also reproduced the idea of ‘Indianness’, ‘Indian culture’ that created a vision of India from their point of view and also erased the history of Dalits globally. Decades later, as some Dalits were able to immigrate, they found themselves exposed to similar forms of oppression and ostracization especially within Indian societies, communities, by Indian employers overseas.

We are at an interesting point in the U.S., U.K. and Europe where the anti-caste discourse is picking up due to decades of national and international lobbying and advocacy work by several Dalit led organisations and other human rights solidarity organisations. In my recent work with International Dalit Solidarity Network, I am trying to assess the efficacy and impact of this network in EU and UK around elimination of caste-based discrimination based on work and descent.

CC: My research centers around artists’ works in terms of themes about borders and boundaries. How does your work explore these themes including physical, emotional, geographic, convergent and divergent boundaries?

JS: My art is a reflection of who I am and all that I have gone through in life as a person and as a Dalit woman. I practice honing mindfulness, intentionality and honesty to create work that questions status quo, systems and power embedded within institutions.

My work is about breaking boundaries and binaries of all kinds, “artist” “audience”, “man” and “woman” “power” “powerless” to move away from societal, institutional and systemic codes and conditioning that often-put people more rigidly into the very labels and moulds they are trying to break out of.

I speak from my professional space of leading and running an organisation, Gender at Work India an Indian affiliate of Gender at Work- a pioneering organisation working on institutional change over the last 20 years. My work in the past few years has entailed strengthening programmatic, strategic, administrative and substantive inputs for DEI, feminist institutions and architectures, feminist leadership and feminist institutions from an intersectional/Dalit Feminist lens within our work. I have regularly advised and supported non-profits, corporates and bilateral to shift their existing narratives around leadership, work cultures and systems from an intersectional/ dalit feminist lens.

Thus, I do not believe in enforcing or promoting borders and boundaries in any manner. For me human connection, relationships and human rights are above any kind of formal, institutional processed. I have seen how governments and institutions coerce people into normality, obedience and complicities which I challenge both in my life and in my arts. For instance, Walking Upon Bodies (2020), Those Whose Stomachs are Full Make Art (2022) Living in Exile (2021, 2022) and Artist Workshop are informed by my life experiences but also by my professional work as they allow me to bring an institutional take into arts.

CC: String is a recurring material in your work. Please discuss the use of string in your performance work, explaining the symbolism and its relationship to the body.

JS: I started playing with Janeu (a ‘sacred’ thread worn and permitted only for upper caste Hindu men in India) in 2019. I wanted to devise a work on caste and body which led me to pick up Janeu for its symbolism of caste purity, chastity and virility in Hindu men. As a dalit queer body, the picking up of janeu itself was a moment of subversion and resistance. I broke down several times during early months of experimentation and forming a relationship with the object. I could not be objective in my practice as the thread has been a historic symbol of violence, oppression and subjugation for my community. I was held and guided by my friend and mentor Manishikha Baul in those days which also allowed me to bring this work to public domain.

performance still from Janeu Prompts

performance still from Janeu Prompts

Over the years, I have played with Janeu but also other threads such as wire, yarn and rope in my work. In 2022, I conceptualised, devised and performed Janeu Prompts. This work was supported by Reframe Grants, Genderalities 2.0 which aimed to go beyond oral and written narratives, to highlight the language of body, psyche, emotions and feelings to respond to ongoing cases of violence against marginalised communities in India. In this work, I used my body in juxtaposition to subvert and transform body (apparent site for violation) as a site of dissent, resistance and assertion.

In 2022, I also premiered new work, Body as Caste Field at Documenta fifteen. Body as Caste Field is an exploratory performative work that showcases a queer, marginalised, non-dominant caste (Dalit) body’s socio-political, geographical location and its navigations within the systemic oppression in South Asia and globally. In this performance, I again worked with my body as the tool to create a web with Janeu and other threads and wires. This web is a symbolic, invisible caste lines that creates divisions and segregation in South Asian society. In the web, I play, dominate, subvert, disrupt, submit and pause to engage with the dark space within one’s body to tap into the embodied material of caste, intergenerational load of pain and collective trauma. This performance explores the body polarity navigating within the caste field. By tapping into the history of systemic oppression to achieve intimacy, personal power over one’s own body, ideas and life choices.

CC: In some of our previous conversations, you mentioned your mother’s activism and her influence on your current work. I’m always interested in hearing about mother/daughter legacies. Please share some insights on this.

My mother, Rajni Tilak was an important voice and figure within Dalit movement and feminist movement in India. She championed rights of Dalit women and other historically marginalised communities across India.

She and I have shared a very difficult relationship which became more and more strained as I grew up. Since I am a single child, growing up with a single mother, who was also an activist was rather challenging and toxic. She was an incredible woman, activist and feminist, but was never home and almost never a mother. I did not receive much love or attention from her. In addition, there was hardly any privacy or safety at home. My parents split up when I was very young and she raised me singlehandedly in a commune of social activists, feminists and political workers across caste, class and genders. I grew up quite early in life and due to her intersectional feminist work, I grew up absorbing the changing discourse across movements. As she manoeuvred through her personal and political struggles and her life changed, my political perspective and feminist ideology became more apparent and nuanced. It is her that I credit for my life that has shaped in a peculiar way, because of the decisions made early on which were quite futuristic. She was a radical, remarkable woman – her tenacity, resilience and generosity are hard to come by especially in today’s time where most people are filled with self-doubts and fears. I have begun to appreciate her more after her death. She taught me to always stand for myself, and against what’s wrong.

Fortunately, as my parents were able to break away from caste-based occupations in their lifetime, my mother’s public presence allowed me a protection from blatant caste discrimination and first-hand experience of untouchability. I am a second-generation learner in my family who has been able to get educated and be free to live my life on my own terms.

The weight of my legacy only became apparent after her death. For the first time, I saw her as a person and human of her own merit. I realised how difficult her life had been and how grateful and privileged I am to be her daughter. Also, as a young Dalit queer woman living on her own, in a deeply patriarchal, casteist and traditional society in India, how much her presence protected me. I am so proud of her and the journey she has had and that I was born to her. However, I am acutely aware that I am not her. My purpose is to amplify her ideology, while continue to heal myself, follow my passions and be free.

CC: Congratulations on your recent acting debut in the film Origin. Please tell us about the project and your experience with the film.

JS: Thank you. I feel honoured and grateful to be chosen for this historical work as I couldn’t have found a better international debut. Earlier this year, I was cast and directed by Ava DuVernay in the film Origin as the only Dalit queer actor in the film.

My experience with Ava and Aunjanue was fantastic. I have never met such a self-assured, calm and fun female director on the set ever before. Since this was my very first time shooting for a Hollywood film, I was nervous. However, it took us no time to break the ice and work together as Aunjanue and I share screen for a short scene in the film. Spending couple hours with them and the crew made me realise that it was possible to enjoy acting without being stressed especially when the director is an African American woman. The vibe on the set was open, warm and friendly which made me comfortable. We rehearsed the lines together and they made sure I was okay. It was truly a gift to work with them.

The film is directed and produced by Ava based on the book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents examining systems of oppression in the United States and abroad by Isabel Wilkerson. This film premiered at Venice International Film Festival in September 2023 where Ava made the history as the only African American Director in competition in eight decades. The film is due to be released by Neon later this year.

Body as Caste Field, essay written with Vidisha Fadescha →

Project Anti-caste, Love: Instagram→

Jyotsna Siddharth: Instagram →

◊

This is the fourth in a series of interviews Colette Copeland will be doing as part of her Fulbright Research Award to India. She’ll be researching and writing about female artists who are working with non-traditional materials and processes.

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.

To read Colette Copeland’s interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

To read Colette Copeland’s interview with Manjushree →