Placing the Image

John Greiner

May 2021

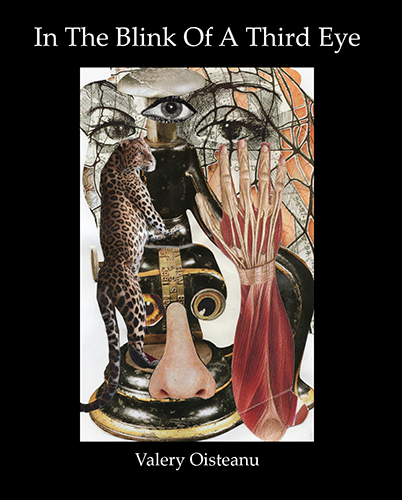

Placing the Image: Valery Oisteanu’s In The Blink Of A Third Eye

The image cut off from classical context and reinserted in a manner contrary to the standard to create a new vision has been an obsession for many artists in the west for some time. This obsession took on a more pronounced position beginning in the mid-19th century as society began to lose touch with the traditions that had grounded it for a millennium. The re-contextualizing of the image for heightened effect has taken various forms, and has been denoted by an assortment of names, the most common being surrealism. Though Valery Oisteanu can be called a surrealist, his most recent book of collage and writing; In The Blink Of A Third Eye allows the reader the opportunity to examine and enjoy the multiple paths that the avant-garde in art and literature has followed in the past two centuries and which cohere as a supra-surrealism.

Image re-contextualized to create a heightened awareness can be seen in its more basic form in cautionary and fairytales. The works of La Fontaine, the Brothers Grimm and Heinrich Hoffman have left an indelible mark on the psyche of many generations. Their tales allowed the authors who followed to create modern mythologies. A writer such as Bruno Schulz examines his own youth through a wondrous prism to create a mythology of his family. Franz Kafka creates a mythology out of bureaucracy that cautions the reader, who seeks to assert their individuality in society, of the probable outcomes of their endeavors.

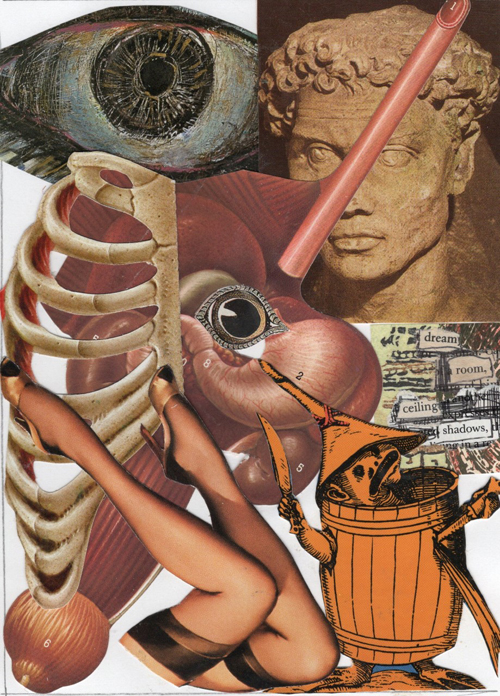

Punk Samurai

Punk Samurai

Valery Oisteanu is aware of the fairytale/mythology as the starting point in the placement of the image to create a heightened effect. Most notably he touches on this in his prose poems/essays. An example is “Leaving For Dreamtime, A Small Giant Dies” where the author falls asleep at the Victoria Art Center to wake into an examination of the Aboriginal artist Nosepeg. There is a magic and mystery to native Oceanic art that Oisteanu approaches through its mythological relevance and background. This approach resembles that used by Raymond Roussel in Nouvelles impressions d”Afrique. The altered subjective impression is the beginning of Oisteanu’s objective observations. It is the eyes of the outsider upon the exotic.

The exotic is essential in Valery Oisteanu’s work in the same way that it was essential for mid-19th century French writers and artists involved in Orientalism such as Flaubert, Delacroix and Chassériau. Like his predecessors, Oisteanu travels through North Africa where

Men in cafes watch the alley’s the female shadows

Morning drive-by, the river girls wash their scarves

Harvesting olives in the withered fields

Cooking, they are taking the shape of a Tagine pot.

Oisteanu is opening himself to the exotic image of Morocco as Flaubert opened himself to the exotic image of Carthage to create Salammbô and later the Egyptian desert in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a novel filled with “surreal” landscapes and the subject of paintings by Max Ernst and Salvador Dali, amongst other. He continues to follow the exotic through Japan and Portugal, back to the land of his birth, Romania, and to Bucharest the “capital of the ‘Absurdistania’ where “a poet talks in a strange language/To a frozen audience.” The exile returned if not understood.

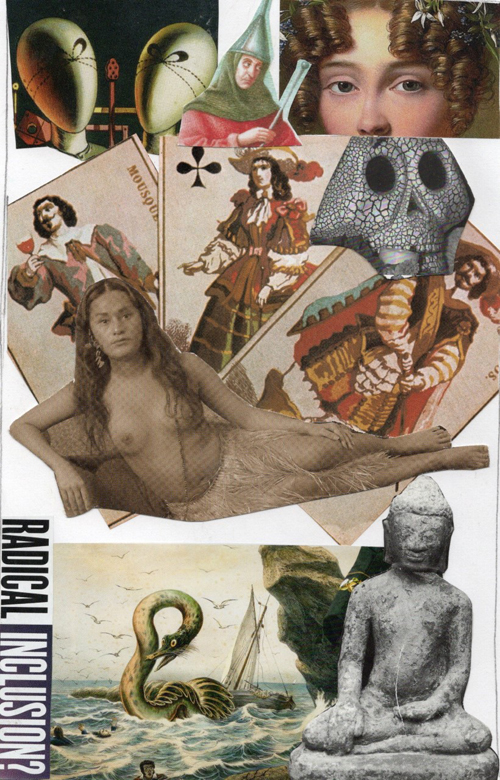

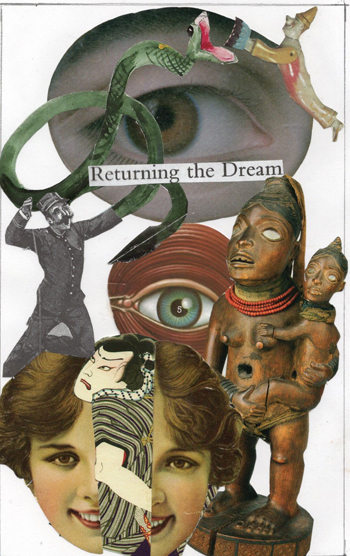

Romania is the homeland of another great artistic exile, Tristan Tzara, one of the founders and the prime motivator of Dada and it is in Dada that we are able to see Oisteanu’s dominant visual influence. There are eighteen collage/illustrations in In The Blink Of A Third Eye. It is here that Oisteanu shows his mastery in the placement of the image to create an arresting aesthetic language. The eye is the most prevalent form in these works. The looking out and beyond is the great beauty of Oisteanu’s work. The influence of the dada past is clearly present, but he goes beyond the past, and the past of dada’s successor surrealism, into the realm of supra-surrealism.

Surrealism, in modern usage, is a problematic term. The word surrealism has been denigrated to the point that it denotes almost any image that is beyond the everyday. Radically original artists of the past such as Bosch, E.T.A Hoffmann, Lautréamont, and the St. John of the Book of Revelations are too often referred to as surreal by many viewers and readers who, for lack of insight, or simply a better word choice, place an inexact connotation upon their work, which, too a degree, undermines the uniquely visionary qualities in their creations. Of course within the surrealist movement there were visionaries; Desnos, Carrington Tanguy, Sage and Breton at his best, to name just a few. Unfortunately surrealism as a movement became the narcissistic hangover of Breton’s and Salvador Dali’s personalities. Moving beyond surrealism, but stuck with the moniker were writers such as James Tate and Frank Stafford. Out of the traditional surrealist movement came the absurdism of the expelled surrealist Antonin Artaud and later Fernando Arrabal with his commitment so different from Dali’s monarchism and Breton muddle headed approach to politics. Arrabal’s compatriot in the Panic Movement, Alejandro Jodorowsky moved towards the mystical in his films. Latin America gave rise to the magical realism of Garcia Marquez, Allende, Borges, Cortázar, etc. who due to cultural and geographical distance were able to establish a greater independence from the term surrealism, though their works still suffer on occasion from being miscategorized as surreal. Too many diverse artists have been tagged with the misnomer surrealist.

Radical inclusion

Radical inclusion

It is essential to move beyond the term surrealism when talking about artists outside of the surrealist movement. We are almost one hundred years removed from the founding of the surrealist movement in 1924. This is a far different time. We have gone further in psychological exploration than the exaltation that Breton experienced in dreams and automatism. The word surreal may be appropriate in some cases to describe situations caused by non-realistic placement of images, but the placement of the image can be done in many diverse visionary styles that are in no way related to surrealism. The artists who place the image should not be confined to the term of surreal.

It would be easy to define Valery Oisteanu and his work as surrealist, but that would fall short in giving proper artistic credit and context. Oisteanu comes from multiple angles in the past to project into the future. In The Blink Of A Third Eye is a look beyond by a man who knows the past and feels the need to go beyond the things that are known. For a lack of a better term Valery Oisteanu could be called a supra-surrealist, but that too falls short. In the end Valery Oisteanu is simply a visionary.

Returning the Dream

Returning the Dream

In The Blink Of A Third Eye

Spuyten Duyvil Publishing →

◊

John Greiner is a writer and visual artist living in New York City. He was educated at the New School for Social Research. Greiner’s work has appeared in Antiphon, Sand Journal, Empty Mirror, Sensitive Skin, Unarmed, Street Value and numerous other magazines. His books of poetry include Circuit (Whiskey City Press), Turnstile Burlesque (Crisis Chronicles Press) and Bodega Roses (Good Cop/Bad Cop Press). His collaborative work with photographer Carrie Crow has appeared at the Tate Liverpool, the Queens Museum and in galleries in New York, Los Angeles, Venice, Paris, Berlin and Hamburg.