Revisiting the Morgan Library and Museum

Ivan Klein

January 2022

Viewing the Exhibition “300 Years at the Dresden Van Eyck to Mondrian”

From the drawing collection of the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden.

Vax card in hand and KN95 mask securely, if not comfortably in place, I approach the relatively new entrance for the public on Madison Ave. just south of E. 37th St. in what was once the headquarters of the Lutheran Church in America. A makeover by the architect Renzo Piano that transformed it into an airy modern museum space and connects it to the original library of J. Pierpont Morgan. That 1906 architectural jewel by Charles McKim fronting on E. 36th St., familiar to me from my four to midnight security gig there on the weekends through most of the 1980s. Back only a few times and not for a long while. The current showing of master drawings from Dresden just enough to get me warily out in public.

Right off the bat I run into what might be called an old acquaintance, the Stavelot Triptych, which used to stand in relative obscurity at the end of the passageway between the old rotunda and the core of the original library. Now the cynosure of the lobby of the museum, the Triptych circa 1100 AD with its rondels depicting the epic journey of the true cross and its reliquary, is shined to a renewed brilliance, its gold and semiprecious stones gleaming. “The earliest surviving reliquary of the True Cross, unique in that it unites in a single work of art Eastern and Western (Byzantine and European) iconographic traditions of the Legend as they existed in the middle of the 12th century,” according to a Morgan Library publication on the subject.

Stavelot Triptych, image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Stavelot Triptych, image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Legend of the True Cross:

Three enamel rondels on each wing, two reliquaries at the center. The rondels to be read from bottom to top. Bottom left: Emperor Constantine’s vision of the cross in the sky that will bring him victory on the morrow. Mid-left: successful battle against Maxentius showing Constantine leading the charge on horseback and spearing his opposite. Top left: the baptism of Constantine with a divine hand above the proceedings.

According to the Legend, Helena, the mother of the Emperor was converted by Pope Silvester after Constantine’s baptism and then traveled to the holy land in search of the True Cross. The right wing of the Triptych depicts her journey and triumphant discovery. The bottom rondel has her interrogating a tight grouping of Jews, most prominent of whom is a certain Judas marked by a banner in Latin stating that he knows the cross’s location. A bonfire in the background is there to loosen his tongue as to the secret which the Jews hold close for their own purposes. The middle rondel shows this very same Judas excavating the Cross of the Lord (Lignum Domini). In the top rondel Helena tests the healing power of this Cross on a man who recovers from a deathly illness as a result. The other two crosses, those of the thieves who were crucified with Jesus, are carried off. — No healing qualities there. Just so much dead wood.

And it is these 2 thieves I hold

most closely to me

as my true kin.

Common and anonymous as I am

& unmourned as I expect

that I will be.

A twelfth century Byzantine poet pithily: “Constantine saw the Cross in the sky while Helena discovered it in the ground.”

The sacred character of the whole is confirmed for believers by a small pouch in the lesser of the two inner triptychs containing what is purported to be fragments from the True Cross, a nail and bits of the Virgin Mary’s garment.

I think of a personal favorite from the great works of what is called the Age of Faith held by the Library. — The Morgan Beatus — Illuminations of Beatus of Liebana’s tenth century commentary on the Apocalypse of John. — “The Woman clothed in the Sun and the Dragon.” — No piddling psychedelic art comes within a thousand miles of this vision of the Virginal Woman of the Sun facing down the multiheaded Dragon of the World. Rarely exhibited, but before me now, in Early Spanish Manuscript Illuminations, ed. John Williams, New York, 1972. The Beatus the foremost among these phantasmagoric takes on Jesus, the Evangelists and the end times. Part of the vast trove of illuminated manuscripts in the Library’s possession that I more or less inhaled on my nightly rounds.

Another strength of the Morgan is its collection of Master Drawings, the greatest in North America. The current Dresden show a natural fit for this historic collection. Again, during my time as a working stiff at the Library, I had enough exposure to the drawings that a certain appreciation set in, so that the paintings for which they were often preparation, seemed almost vulgar by comparison.

As I make my way to the Dresden exhibit, my thoughts drift to the Library guards and maintenance men that I worked with. — John T., a lanky black guy, assistant chief guard, who talked of epic schoolyard games up in Harlem that nobody much remembered because nobody much became anybody. Nonetheless, we found a ground for real basketball talk in our mutual knowledge of W. 4th St. and Rucker players gone by while watching the security screens in the consul room. There was crusty Joe V., an older fellow who waxed the floors deep into the night with his portable radio blaring at peak volume on the twenty-minute A.M. news cycle the whole time. We started out on the wrong foot, but certain bits of information I added to the Readers Digest stories he read on his breaks smoothed the way. Even made myself surprisingly useful once in a great while. Then there was Walter G., the Ukrainian immigrant in charge of heating and cooling and such matters, whose older brother was shot by the Nazis in one of those ten for one deals after a German soldier had run afoul of townspeople and been killed. Loving the memory of his brother and still sympathetic to the Nazis’ racial views. Not a problem. Always comfortable with anti-Semitic feelings freely and frankly expressed. We both knew where we stood with each other and yet it pleased him the last few years I was there to wish me a happy Passover when we met at the workmen’s eating table down in the basement.

A revelatory showing of Hebraica from the Valmadonna Trust, early manuscripts from a most distinguished English collection, featured at the Library in 1989. An elderly white guard, who I didn’t know too well, came over to me and said of the exhibit that it was really beautiful, just beautiful, — what was forbidden, hated, scorned, before his eyes with its somewhat mutilated dignity intact. Looking through the Catalogue that was published for the exhibition, I turn to a page from an Ashkenazic prayer book printed in Venice in 1567. Broad vandalizing strokes of brown ink across the page courtesy of a suspicious and ignorant censor. — A page that was shown in the Morgan Valmadonna Exhibit. Perhaps that elderly guard felt the weight of it when he sought me out.

All of the men I remember from back then comprising a literal underclass in the hierarchy of the Library, remarkably humble and caring, even tender toward each other compared to those above them in the order of people and things. Also, the influence of the institution’s culture somehow seemed to rub off on all of us in one way or another.

Works on paper from the Kupferstich Kabinet. Dresden:

We start our unguided tour with Andrea del Verocchio’s “Madonna with the Brooch” ca. 1470-71. Silverpoint and leadpoint with light brown wash on white paper. The Catalogue notes that the sheet was originally attributed to Leonardo de Vinci and that the identity of the actual artist is still in dispute. No argument that it’s breathtaking. — Eyes averted modestly, but full lips, full breasts, the knot of her kerchief falling just above her cleavage. Great beauty on a fine line just this side of voluptuousness. — An artist and a young model of the age of the Renaissance in Florence.

Carlo Maratti — “Self-portrait” — Rome, ca. 1680-85. Red chalk.

Handsome, vain, his quaffed hair down to his shoulders. The Museum post says around age sixty. He looks half that. Fine nose, straight lips curling upwards ever so slightly. — He can hardly keep himself from smiling, he feels himself so handsome. — “One of the preeminent painters of the Roman baroque…” — The immersion in the created self — isn’t that in large part what is meant by what we might call contemporary sensibility?

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) Monks Reading ca. 1812–20 7 15/16 × 5 1/2 in.© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photography by Herbert Boswank

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) Monks Reading ca. 1812–20 7 15/16 × 5 1/2 in.© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photography by Herbert Boswank

Francisco De Goya, “Monks Reading” ca. 1812-20, Bordeaux. Brush and brown wash. The brown wash is the perfect tint for the equivocal goings on. What meets the eye suggests men’s fathomless depths as in Herman Melville’s ambiguities and profundities. — Three monks devouring a text, a fourth looking over their shoulders. Wait — are my eyes failing me, or is that the shadowy World Serpent leaning into the onlooker’s ear with whatever filth he has to spew?

Behind the scrum of grouped figures is what appears to be an old monk with a woman at his back both looking more than a bit down and out. If they were once lovers, the passion is long spent. And maybe those monks aren’t poring over a sacred text, but a pornographic special just for their kind. — One wouldn’t put anything past these clownish hipsters — the quirks and tendencies toward madness that Goya, my favorite artist, with his knowledge of the skeletons in the closets of men’s minds, understood by virtue of a very high degree of experience and perception.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669) The Abduction of Ganymedeca. 1635. 7 5/16 × 6 5/16 in. © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche KunstsammlungenDresden, Photography by Herbert Boswank

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669) The Abduction of Ganymedeca. 1635. 7 5/16 × 6 5/16 in. © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche KunstsammlungenDresden, Photography by Herbert Boswank

Rembrandt — “The Abduction of Ganymede” ca.1605, Amsterdam. Pen and brush and brown ink.

Bulfinch describes Ganymede, the son of a Trojan king as the most beautiful of mortals and Ovid’s Metamorphoses has Zeus, fired by passion for him, taking the form of an eagle and flying off with him to Mount Olympus to serve as cup bearer for the gods.

In Rembrandt’s strikingly modernist drawing, the weighty, rather awkward young child, is being borne kicking and screaming to the service of the Chief of the Gods from this Earth on which he has happily dwelt. Rembrandt who always found and distilled what was most human in stories of the divine, shows in the subsequent painting the distraught child pissing in terror as the eagle, intent on his sordid business, carries him away.

Kathe Kollwitz — Frontal Self-portrait, 1911, Konigsberg. Black, grey and violet chalk on brown paper.

The artist in her early forties. This and a series of self-portraits she executed over a number of years elicits the statement from the Catalogue that “the external [is] a mirror of the internal.” That is, the truth of self-portraiture is finally beyond the artist’s control, and in this particular dark drawing, the unsparing integrity of a true soul commands our attention and respect. — Right side of her face fairly lit, the left side darkening, as if in anticipation of its mortal end and dissolution.

Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) Portrait of an Older Man ca. 1435-40. 8 7/16 × 7 1/16 in. © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photography by Herbert Boswank

Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) Portrait of an Older Man ca. 1435-40. 8 7/16 × 7 1/16 in. © Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photography by Herbert Boswank

Jan Van Eyck — “Portrait of an Older Man” ca. 1435-40. “Netherlandish.” Silverpoint and goldpoint on white paper.

The featured portrait graces the cover of the Catalogue and is the lead for the show’s media publicity.

Once thought to be Cardinal Nicolo Albergati. Now simply an aging unknown scholar. Austerely robed, with straight lips, steady eyes.

Everything superfluous fallen away with the years. There doesn’t appear to be a trace of vanity or pretense about him. As he sits for the renowned artist, is he thinking of the time that has gone by or of the time that remains? Perhaps what is most striking about this brilliantly realistic portrait is what seems to the subject’s total acceptance of the existent moment.

The painting that Van Eyck did from the drawing seems to me to be ever so slightly less grand, although highly accomplished, to be sure. In the painting, a faint trace of anxiety steals across the old man’s face, as if just a bit of self-consciousness and the discomforting awareness of approaching death have crept into the artist’s hand and hence to the canvas.

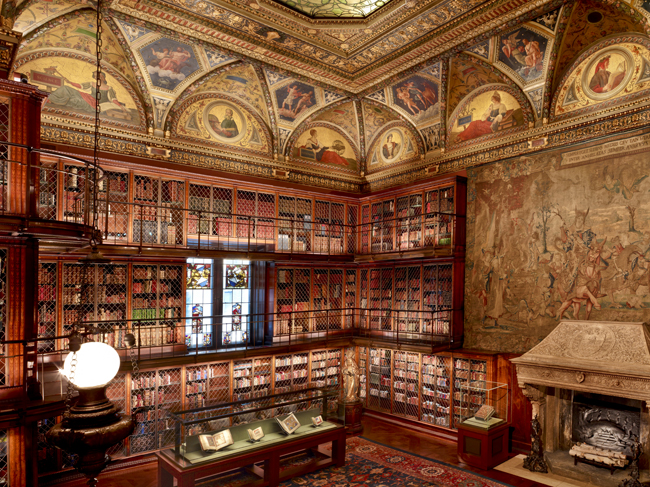

It’s getting late, getting crowded and I break off, make my way through the new dining area and gift shop, remembering the grandeur of the original library — the West Room with its enormous desk upon which sat a solid gold frog rumored to be worth millions and its red plush walls — the great financier and monopolist’s personal study — and the East Room, that gorgeous repository of priceless bibliophilic treasures. It’s almost like coming home.

Pierpont Morgan’s Library The Morgan Library & Museum Photography by Graham Haber, 2014

Pierpont Morgan’s Library The Morgan Library & Museum Photography by Graham Haber, 2014

Van Eyck to Mondrian: 300 Years of Collecting in Dresden

October 22, 2021 through January 23, 2022

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue, New York, NY

◊

Ivan Klein published Toward Melville, a book of poems from New Feral Press, in July 2018. Previously published Alternatives to Silence from Starfire Press and the chapbook Some Paintings by Koho & A Flower Of My Own from Sisyphus Press. His work has been published in the Forward, Urban Graffiti, Otoliths, and numerous other periodicals.

Other essays, reviews and poety by Ivan Klein on Arteiodolia→

For information on Ivan Klein’s latest book

The Hat and Other Poems and Prose from Sixth Floor Press

click here →