What’s the Title? TITLE

Ron Morosan

December 2018

Now that the concept of the avant-garde is over a hundred years old, and has become the official label of radical experimental art and literature, is it still a relevant idea, or something that can still break open new ground? What is avant-garde in poetry these days? It seems that it is still open territory in many respects. We’ve all read Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Cummings’ XLI Poems, and Apollionaire’s Calligrams, all wonderful inventive statements of new ways of looking at the world through language. Yet, we must still ask: “What is a poem?” as Charles Alexander, the publisher of Gavronsky’s book, says.

Serge Gavronsky has achieved something in his poem/novel Whats the Title? TITLE, that has a structure, a concept and a kind of inventive form that qualifies as being called avant-garde, The reasons for this are many and I will try to list some of them here and why I see them as avant-garde.

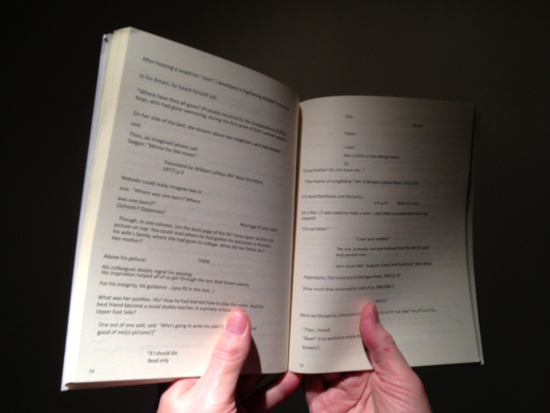

Gavronsky’s book calls itself a poem/novel. That alone is a formidable statement of purpose. My initial response was to try to imagine Wallace Stevens writing a novel in the style of William Faulkner. But then, on starting to read Gavronsky’s book, I realized I was being engaged in a very fresh and innovation form of narrative; I was starting to feel like a participant. His approach in relating his story is to break up the narrative into a kind of verbal stage direction, using punctuation and large open spaces between words and sentences, with some sentences being arranged so that the reader is invited into a choreographed reading experience. These spaces become areas where we must fill in meaning or imply potential passages. Overall, my experience of this process became more and more interactive and caused me to feel part of the flow of the poem/novel.

What story is being told in Gavronsky’s poem/novel? It is a tragic Holocaust story, and a story of evidence and archives and who interprets and understands them, and what is understanding, anyway. This story is a multifaceted narrative that suggests a kind of Cubist mural, a huge epic drama told through shifting voices that are sometimes the authors, sometimes the children, sometimes “The Novelist,” and sometimes other authors whose words are quoted throughout the text.

Once engaged in reading this poem/novel one realizes that the setting of the work is a stage set and that this set is a kind of library with book shelves all around on every wall. But then it is clear that the author Gavronsky is on this stage and so is the reader. This is a drama that is as much a play as it is a poem, a novel, or a memoir, of which it is all of these.

But throughout the poem/novel Gavronsky is giving instructions on how to read this work. (This is as if we are being directed by a theater director.)

The introduction seemingly titled: THEN gives the following source material:

“The narrative completed through the cooperation of the reader”

Wolfgang Iser, “The Implied Reader,” Baltimore: John Hopkins Press 1978, p. 113

Throughout the text, quotations and citations give interpretation and translation to what is taking place in the narrative. In some cases this is very directly stated, as in:

“What is not clear is what is clear”

Laura (Riding) Jackson “The Poems of Laura Riding,” ( Persea Books, inc. 1980) p.177

Various players appear throughout the poem/novel and prominent among them is The Novelist. The Novelist is on assignment to write about how a small village in France dealt with the war and the Nazi occupation. He appears at various times and makes statements that reveal deep messages about the content of the narrative. At one point he says:

“I asked Myself, how do you translate what is printed, when truth is uninformed? I was about to say, uniformed, as the meaning of life is a lie.”

Continually throughout Gavronsky’s poem/novel we feel we are being presented with evidence of scholarly findings and citations that seek to provide a telling of the events of the horrors of what the Nazis did in France, but the scholarship always seems lacking, to not really be capable of conveying the experience of the pain of that time. This scholarship also conveys the sense that the stage is also a courtroom and the reader is one of the juror/witnesses who must render an interpretation.

Again, What’s the Title? TITLE is a constantly shifting narrative that keeps the reader engaged in a feedback loop of interpretation, where the evidence of what happened is presented in multiple modes, as if a circular causality is being sought in the narrative and what is left out is as important as what is included. The reader is put into the position of causing the meaning to be created, to fill in the narrative by imaging how horrible the experience was and experiencing it again.

Yet, amidst all the intensity of narrative is a humor that has a quality like Zero Mostel: it’s all just life, absurd, meaningless, but interesting, even entertaining. We are brought back toward the end of the book to Gavronsky’s memoir through references to violin lessons, teaching in a college, an encounter with a Russian spy, all apocryphal or not: who knows?

This is a book I didn’t want to end reading. So I will read it again.

◊

Ron Morosan is an artist, writer, and curator. He has shown his work internationally at the American Pavilion of The Venice Biennale and the Circulo De Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain. In the US he has shown at the New Museum and had a one-person exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum, and at numerous galleries in New York. He curated the Robert Dowd exhibiton, Subversive Pop, at Center Galleries in Detroit, as well as Denotation, Connotation, Implication at Eisner Gallery, City University of New York. He has written catalogues for many artists, including Enid Sanford, Tom Parish, Robert Dowd, and others. In the 1990’s he started and ran B4A Gallery in Soho, New York, writing press releases, articles, and catalogues.