Two Baseball Stories by Zane Grey

Ivan Klein

April 2024

He was famous for his novels of the Old West, was said to have created the genre with his best-selling Riders of the Purple Sage. But there exists a mainly forgotten body of his baseball fiction and lore as well, that celebrates and chronicles the glorious early morning of the game.

We have “The Red-Headed Outfield,” the title story in a 1920 collection that captivated me as a kid; Manager Delaney has a trio of redheads playing the outfield for his Rochester Stars as they contend for the pennant of the “fast” New England league against the Providence Greys. Red Gilbat, an irrepressible zany in left field, is hitting a very neat .371; talented Reddie Clammer, a showboating ladies’ man, is in right, and Reddy Rey, a great collegiate sprinter and batting champion, is Delaney’s centerfielder. In the fifth inning, Red Gilbat astonishes the Providence crowd by stepping to the plate in a full-length linen duster and driving the ball over the left field fence. Thereupon, he picks up the tails of his coat and minces his way around the bases until an aggrieved fan yells “Redhead!” at him. This drives Gilbat wild and sends him into the stands in search of the offending voice, at which time he is enveloped in a maelstrom of partisans for the Providence side yelling “Redhead!” at him to a man.

(An aside on baseball dress of this early period: Carl Sandburg, in his autobiographical Always the Young Strangers, wrote of a country nine that surprised his Galesburg, Ill. Town team with “a tall gawk wearing a derby hat” who made a leaping, game-saving catch and throw from centerfield. Sandburg speculated that the gawk had probably forgotten or misplaced his ball cap at home, but I think it just as likely that he was demonstrating a certain insouciance, a certain contempt for town usages and standards. Secure in his superior talent, perhaps he felt he could dress and do as he pleased, just as did the fictional Red Gilbat).

Redhead! — The shame of it. — The reason not at all clear to me. But a serious epithet. A throwdown. And in August 1996, on the way home from my father’s funeral, a story is conveyed to me by a family member as to how redhead that he was — he who would have bright red hair through his young manhood as a truck driver and teamster organizer and who was known in union circles as Red Klein even after his hair had turned wispy white — had, as a young child of that proximate time, poured a bottle of black ink on his head to obliterate the carrot color that in Zane Grey’s baseball fiction was the cause of insult and riot.

There are no substitutes available after the disappearance of the Rochester side’s feckless leftfielder in the stands, and now we have the two remaining reds sharing the entire outfield between them. Then Reddy Clammer, the hotdog, smashes his pretty-boy face into the fence making a circus catch, and we are left with the impossible prospect of the champion sprinter Reddy Rey tenanting the entire outfield by himself for one fateful inning. There is a breathless description of a high arcing fly ball falling toward the right field corner and the great ball hawk closing an immense amount of ground to make the crucial catch. — The achingly beautiful aesthetic and drama of the game captured in a nutshell.

______________________________

“Old Well-Well” is the last story in the collection. — “He was Old Well-Well, famous from Boston to Baltimore as the greatest baseball fan in the east.” — A huge lumbering man now much diminished, he is observed at the 25¢ ticket window and then taking his seat half-way up the right field bleachers. The narrator has heard that Well-Well’s nephew and protégé, a rookie, will be playing center field for the Phillies this day and that illness had forced Well-Well to miss a previous opportunity to see the boy play for the team he had rooted for all of his avid, baseball-loving life. He was old Well-Well, and the name derived from “his singular yell which had peeled into the ears of five hundred thousand worshippers of the national game and would never be forgotten.”

The setting is the historic Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants and the narrator’s loyalties are naturally with the home team. But he sees the shadow of pain and death on Well-Well’s face, senses the struggle in the old man’s soul as his nephew excels at bat and in the field. Finally, he secretly begins to pull for the Phillies despite himself.

Well-Well passes up several opportunities to give out with his legendary bellow as the game moves toward extra innings. The nephew makes a spectacular game-saving catch and plunges over the outfield ropes into the crowd. — An unwalled open field of play to go along with the fresh and open enthusiasm of young America. — Finally, the old man’s kin hits an inside-the- park homerun that ends the game in a cloud of dust at the plate, and he can’t contain himself any longer: “Well! — Well! — Well!” — An earsplitting stentorian blast that echoes off Manhattan’s Coogan’s Bluff and leaves the narrator momentarily deafened. — It is the end of the old fellow and his nephew, the hero of the day, has leapt into the stands to be at his side as the ambulance takes him away.

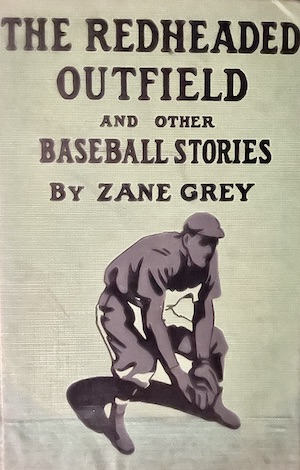

A few years ago, I stumbled upon a first edition of The Red-Headed Outfield and Other Stories at an antiquarian book fair in Greenwich Village. The original dust jacket has a rendering of the left side of a diamond with a batter in his crouch starting to sprint toward first base after making contact, the catcher slightly raised up following the flight of the ball, vaguely drawn crowd faces blending together. Everything frozen in time for nearly a hundred years on the front of this most genuine, worn-at-the-edges book of baseball. The title announces itself in ornate red lettering and underneath, on the reasonably well-preserved hardcover, the embossed figure of a real old-time infielder — earnest, knees bent, the glove on his left hand miniscule by modern standards — more like a mitten — his head down underneath a barely peaked cap, he is ready to snag whatever comes his way with two honest hands.

It’s true that baseball is merely a pastime, but I agonize with critical and not so critical balls and strikes affecting my woebegone Mets from April through September (October being a rare time for our team), and people at the ballpark pray openly and unashamedly for our side, and I suppose, the other side while none dare call it blasphemy. It has been noted that the game brings us somehow closer to a feeling of the eternal while unbearably heightening the very moment. —

Something about its stately pace and endless variations, its matchless beauty and raw, honest drama. — Something of what the great Japanese poet Shiki must have felt when the game was first introduced to his country and he observed it being played as an invalid dying of tuberculosis:

All those bases

loaded,

and somehow my heart is loaded too —

palpitating!

This is how my lonely old boozer of a friend, Jim, must have felt as well, going out to thirty, forty games a season. Just getting out to the park a bit later for batting practice as the years went by, is what he quietly let out.

The unbearable saraband of mortality and infinity — the old horsehide — its smell and grip. — The buzz of the stitches as they fearfully whiz by at the plate. — The feel of bat meeting ball most sweetly and these grown men now, playing the game for us.

The ballpark as a huge theater of our nature;

the game itself without limitations in time.

Time without margins

and space cohering to the soul’s delight

◊

Ivan Klein’s most recent collection is The Hat and Other Poems and Prose from Sixth Floor Press in 2021. His other books include Toward Melville (New Feral Press) and Alternatives to Silence (Starfire Press). You can also find his writing in Leviathan, Long Shot, Flying Fish, The Jewish Literary Journal, The Forward, and in the great weather for MEDIA anthology Paper Teller Diorama. He lives and writes in downtown Manhattan.