Alice Rahon’s “Ixtaccihuatl”

Daniel Barbiero

November 2021

Ixtaccihuatl: a prose-like poem by Alice Paalen Rahon

L’Ixtaccihuatl, nommée par les dieux, la femme endormie le

visage tourné vers le soleil levant.

Toujours jeune géante, amante blanche de neige et d’aubes

millénaires, mirroir magique à l’échelle les plus grands rêves où

l’homme s’est miré.

Ixtaccihuatl, Femme blanche, montagne sur le haute plateau,

aux flancs de neige et de silence, porteuse d’horizons à venir.

…

Ixtaccihuatl, named by the gods, sleeping woman, her face

turned toward the rising sun.

Always young giant, white lover of snow and of a millennium

of dawns, magic mirror the size of the grandest dreams in which

one gazes in fascination.

Ixtaccihuatl, white Woman, mountain on the highest plateau,

flanks of white and silence, bringer of horizons to come.

— translation by Daniel Barbiero

…

To begin at the beginning, with the very first word: the proper name “Ixtaccihuatl.” But a proper name of what? Of whom? The poem doesn’t decide; its accumulation of descriptive epithets could, by a reading licensed by either possibility, apply to the one or to the other—to a person, to a personified object. To this ambiguous entity known as “Ixtaccihuatl.”

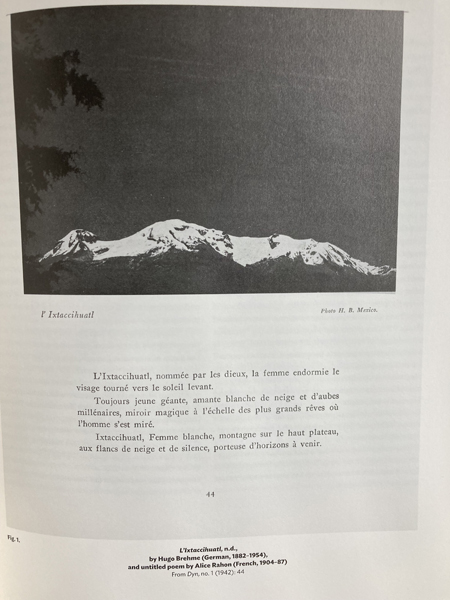

And in fact the poem doesn’t have to decide. Although upon its publication it appeared below a photograph of a mountain—actually, a dormant volcano–clearly captioned “Ixtaccihuatl,” the photograph is a clue more misleading than clarifying, perhaps like a sign with an arrow pointing in the wrong direction—misleading precisely because it is an arrow with only a single point. Because Ixtaccihuatl could either be a who or a what depending on which Ixtaccihuatl one has in mind. “Ixtaccihuatl” is a Janus-faced name under whose sign both a sleeping woman and a dormant volcano comfortably fit.

But what of the epithets themselves? To what use are they being put? What type of speech function or act do they perform? Do they occur as part of a salutation? A summoning? A simple description? It could be any of these, or all of these simultaneously. Or perhaps none of them at all.

…

Alice Paalen Rahon wrote this prose-like poem in Mexico, where she and her then-husband, the painter, art theorist and anthropologist Wolfgang Paalen, settled in late 1939 after having left Paris for the Western Hemisphere. They, like André Breton, Max Ernst, Benjamin Péret, Yves Tanguy and others, were part of the larger diaspora of European Surrealists driven into North American exile by the Second World War. In Paris in the 1930s the Paalens had been part of the Surrealist circle, a time during which Rahon had been most active as a poet; her first book of poetry, Même la terre, had been published in 1936 by Éditions Surrealiste through Breton’s intercession. By the early 1940s, though, Paalen had formally broken with Breton and began publishing the journal DYN, which served as a vehicle for his own independent circle of writers, visual artists, and anthropologists, to which Rahon naturally belonged.

Rahon’s poem appeared in 1942 in the first number of DYN, beneath a photograph of the volcano by Hugo Brehme, a photographer originally from Germany who had resided in Mexico since 1908. The volcano is part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt chain of volcanoes southeast of Mexico City; it consists of four snow-covered peaks that give it the appearance of the profile of a white-draped woman lying on her back. Hence the name the Huatl-speaking indigenous people gave it–“Ixtaccihuatl,” meaning “white woman.” In Spanish it is “Mujer Dormida,” “sleeping woman.”

On one reading, Rahon’s “Ixtaccihuatl” can be interpreted as a simple description of the geological feature that is this dormant volcano. The poem reaches beyond that, though, and evokes as well the legend surrounding it. In this regard it reflects her interest in native North American folklore and mythology.

…

According to at least one version of the folktale—apparently there are several—Ixtaccihuatl was an Aztec princess who loved Popocatépetl, one of her father’s soldiers. Her father promised Popocatépetl that if he could successfully invade Oaxaca—or bring back an enemy king’s head, here versions of the story differ—he could marry Ixtaccihuatl. While Popocatépetl was away on the mission word was brought back to Ixtaccihuatl that he’d been killed; on hearing the news, the princess died of grief. Popocatépetl hadn’t been killed, however, and when he returned and found Ixtaccihuatl dead, he carried her body to Tenochtitlan and laid it down on a funerary table, where he kept vigil over it. The gods, taking pity on them, turned them into mountains in order that they could always be side by side.

Reduced to its structural elements, the folktale is the story of a hero setting out on a quest upon whose successful completion an object of desire, in the form of a princess, is to be obtained. The task assigned to the hero is secretly intended to be an impossible one, and even though the hero doesn’t fail as he is meant to, he becomes the victim of an act of trickery when he is falsely reported to be dead. In the tale the motivation behind the trickery appears to be obscure, but one version has Popocatépetl’s fellow soldiers participating in the deceit because they wanted Ixtaccihuatl for themselves. (Perhaps trickery which, along with the assignment of an impossible task, is one of the fundamental plot elements Propp identified within the structure of folktales, was simply needed to move the story to its denouement.) In any event, trickery has fatal consequences for the princess, and thus the hero’s quest, while successful on one count, fails to obtain the object of his desire. Only the intercession of the gods can reverse failure and unite the hero with the princess, through their metamorphosis into features of the natural landscape.

But Rahon’s poem doesn’t retell the folktale; rather, it is concerned with the post-mythological, metamorphosed Ixtaccihuatl. It takes place in the afterlife of the myth, in which the events the myth narrates can be taken for granted as having taken place in an ahistorical before-time, and in which its conclusion is, literally, inscribed in the earth as a fact of nature. Rahon’s Ixtaccihuatl now belongs to our time, a time the poem describes as marked by the mundane passages of the sun seen through a “millennium of dawns.”

…

On one reading of Rahon’s poem, Ixtaccihautl appears alone, without reference to Popocatépetl. Such a reading may reflect Rahon’s own early feelings of isolation when she first lived in Mexico. Or perhaps Popocatépetl is present in the poem after all. The phrase “l’homme se miré” can be read in different ways, given the ambiguous meaning of “l’homme.” “L’homme” could refer to humanity in general, as in the translation above; or to a specific man. The tone of Rahon’s poem seemed to me to call for the first interpretation, an interpretation grounded in an understanding of myth as the carrier of meaning in a perennial, universal guise, and so I’ve translated it that way. But Popocatépetl may nevertheless still be there by implication if we keep in mind the nesting meanings of “l’homme”: first as the specific man Popocatépetl, gazing at the “magic mirror” of Ixtaccihuatl’s inert body; and secondly as the particular embodiment of a universal humanity knowing itself as essentially finite and provisional in its being, a finitude and provisionality that is revealed through its confrontation with the self-coincident and seemingly unchanging plenitude of a massive geological feature. In both instances we might suggest that what the “magic mirror” reveals is the experience of difference: of Popocatépetl the man as other than Ixtaccihuatl the woman, or of Popocatépetl epitomizing the sentient human, divided from him- or herself by the necessity of acting toward a future he or she is not yet, as other than Ixtaccihuatl the insentient massif.

It is precisely as a polysemic noun that “l’homme” functions as an aporetic name whose semantic field synthesizes the before-time of myth with the present moment in which it endures, and the indeterminate future in which it can be expected to persist. As such, it is a reminder that mythical figures like Ixtaccihuatl and Popocatépetl point beyond themselves. They are signs or symbols of meanings that transcend their functions in a given story.

…

If Rahon’s poem isn’t a retelling of the Aztec myth, or a description of a feature of the local landscape, what is it, or what can it be? I would suggest that it is a text whose meaning consists in the identification of two unlike things. On this reading it reveals itself to be a Surrealist image, but of a highly elaborate and unusual kind.

The Surrealist image, as Breton described it in the first Manifesto of Surrealism, is the product of the fortuitous bringing together or reconciliation (“rapprochement”) of two distant realities whose relationship goes beyond simple comparison. In Rahon’s poem, the distinct realities of Ixtaccihuatl the mythical person and Ixtaccihuatl the volcano are merged and mutually absorbed, the one into the other, and fused under the sign of a single name; the equivalence that results would seem to produce the “luminous phenomenon” Breton hoped to find in the meeting of incongruous things.

The incongruity at once separating and joining both referents signified by the name “Ixtaccihuatl” is an ontological incongruity. Ixtaccihuatl the person and Ixtaccihuatl the volcano embody two very different kinds of being; they inhabit widely separated ontological regions. Consider that human being, even the mythological representation of human being, is the being whose being consists of projecting itself into a future on the basis of choices defined by its available possibilities—a being whose being consists in a self-aware questioning of its own being through a constant dynamic of self-transcendence toward what it is not yet, in light of what it no longer is. By contrast, a volcano is of a completely different ontological structure, one for which it makes very little sense to speak of possibility, unless possibility is understood as something that comes to it from outside—from mechanical forces within the earth, or the effects of human activity.

When the poem speaks of “Ixtaccihuatl” it creates the conditions for an ontic substitution, for the exchange of one being for another and in addition, of an exchange made across greatly distant ontological territories. Through it, what can be said of the one can be said of the other, an instance of figurative predication linking objects across an abyss.

…

It is through the shared name that Ixtaccihuatl the landmark and Ixtaccihuatl the mythical person merge. This isn’t a case of metaphorization in which one meaning is pushed down below the surface of a second meaning, much less an instance of a metaphor based on a perceived shared quality. (Although it is interesting to note that both the lifeless body of the princess and the dormant volcano can be said to be “sleeping,” a shared condition memorialized in the volcano’s Spanish name.) It is instead a kind of coexistence in diune form, two manifestations of the same thing. In the myth, this coexistence or co-identity comes about by the physical metamorphosis worked by the gods. In the poem, it comes about through the linguistic alchemy of the name. The “Ixtaccihuatl” of Rahon’s poem can be read as signifying either entity without compromise to the text’s internal coherence. To the extent that it associates under one name two entities with radically different structures of being, Rahon’s poem effectively leverages an ontological incongruity into a Surrealist image.

…

Interestingly, Paalen claimed to have found an instance of the identification of woman with volcano arising within a traditional mythical-symbolic order. In his April, 1943 essay “The Volcano-Pyramid,” Paalen cites the anthropologist James Frazer to hypothesize that for early humans, the fire within the volcano came to be symbolically associated with a woman’s keeping fire within the hearth. For Paalen, this suggested that the volcano was seen as an “earth mother…who keeps a fire in a subterranean place.” If so, this would seem to suggest that the same order of ontic exchange at the heart of the Surrealist image could be found at work in the mythic image as well, through its identification of unlike with unlike on the basis of a discovered association made possible by a cognitive outlook grounded in a logic of correspondence.

If Paalen’s suggestion of a historico-mythic connection between woman and volcano is valid, it implies that Rahon’s Ixtaccihuatl, while fulfilling the condition of incongruity through which the Surrealist image is created, nevertheless represents a weakened version of that image. For, as Breton declared in the first Manifesto, “for me, the strongest [image] is that which is arbitrary to the highest degree.” By this criterion—the criterion of arbitrariness—the ontic exchange between woman and volcano in Rahon’s poem and more generally, to the extent that it is made on the basis of an imputed shared function of secreting fire, is not entirely arbitrary. Both are thought to “do” the same thing, to parallel each other in their custodianship of fire; the correspondence is drawn quite logically between the natural phenomenon and the domestic function. The correspondence may be imaginative, but it “makes sense” in an almost mundane way. To that extent, it represents a weakening of the image—but not its annulment. The correspondence forged is still ontically incongruous; the equation of woman and volcano is still “convulsive,” in the sense that Breton would have beauty be “convulsive.”

As it is fortuitous, another of the qualities Breton sought in the correspondence constituting the Surrealist image. Here, the fortuitous quality of the correspondence consists in the morphological coincidence of the four-peaked volcano and the shape of a woman sleeping on her back. Seeing the one in the other is arguably just the kind of insight into the marvelous that the Surrealist image would purport to provide. That Rahon’s poem doesn’t make the discovery of this fortuitous morphological coincidence but rather assimilates and plays upon its mythological enshrinement doesn’t lessen its impact. The double vision is still there, encoded in the poem’s summoning of the ambiguously referring name. If anything, the indigenous drawing of an ontically incongruous correspondence on the basis of a fortuitous morphological coincidence shows the affinity between the mythopoeic attitude and the Surrealist attitude.

The suggestion that the Surrealist image and the mythological image share a common structure likely would not have surprised Breton. On the contrary, he would have understood this isomorphism as further proof of the psyche’s natural capacity to forge marvelous associations. Nor would Rahon be surprised to see mythical images repeat themselves in contemporary forms. The assumption that they could, and would, is one of the undercurrents running throughout her work, whether expressed as poetry or painting.

Works referenced:

André Breton, Manifests du surréalisme, (Paris: Gallimard/Folio, 1992).

Wolfgang Paalen, The Volcano-Pyramid, in Form and Sense (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2013).

V. Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, tr. Laurence Scott (Austin: U of Texas Press, 1968).

Alice Rahon, “Ixtaccihuatl,” with photograph by Hugo Brehme, reproduced in Annette Leddy & Donna Conwell, Farewell to Surrealism: The DYN Circle in Mexico (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute: 2012).

Shapeshifter by Alice Paalen Rahon

The first complete compiliation of Rahon’s three hard to find books of poetry recently published by

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places & Wooden Mirrors with Cristiano Bocci and In/Completion a collection of verbal and graphic scores by composers from North America, Europe and Japan, realized for solo double bass and prepared double bass.

More by Daniel Barbiero on Arteidolia →

Daniel Barbiero’s book As Within So Without & other essays has just been released on Arteidolia Press.