“Letters” – A Review

Daniel Barbiero

April 2023

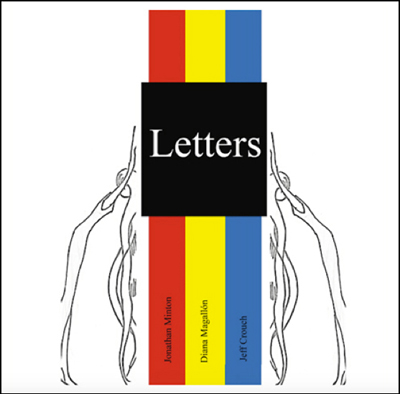

Letters

Poems by Jonathan Minton

Visuals by Diana Magallón and Jeff Crouch

Moria Poetry, 2022

“Letters” can refer to written messages between a pair or more of correspondents, or to the basic graphic elements of a written language. Both types of letters are the inspiration behind Letters, a richly imaginative collaboration between poet Jonathan Minton and visual artists Diana Magallón and Jeff Crouch. But letters of either type are only a point of departure; Minton’s poems comprise a densely allusive world of their own, and one thick with polymorphic meaning.

As we might imagine, a number of the poems deal directly with letter writing or epistolary content. For example this poem, which announces itself as a letter from the outset:

This letter begins with a blinded god, his golden mask.

Someone else is speaking as a ghost.

Someone else is still drowning in the dark.

When the language is private, I recover an image:

wet rock, or a red canyon.

When spoken, you appear with her bare, white shoulders.

This letter begins as a sound from a king’s mouth.

You stand now before a narrow cave and listen for the echo.

This letter begins with locusts and wild honey.

It feeds the hermit as he sits cross-legged in his hut. He is clothed

in a thousand little words like this. It is a murmur. It is a state.

As we can see, this is no ordinary letter. Like the other poems in the collection, this one is constructed out of an elaborate, vividly rendered set of images that point to a recondite symbolism. We encounter a number of archetypal figures—the blinded god, the ghost, the king, and the hermit—that take their place within a privately held language conveying something that in the end is a “murmur,” perhaps connected to a specific yet undefined “state” (of emotion? Of being?). We may not be able to penetrate through to their original meanings, but we can see that they are charged with an affective force that associates them with some powerful experience, real or imagined.

Although the majority of the poems in Letters don’t take an explicitly epistolary form, many of them do appear to incorporate the kinds of reminiscences, reflections, and revelations we would expect to see shared between correspondents on intimate terms. But Minton transforms them into stunning and highly developed imagery hinting at meanings that extend beyond the immediate occasion. For example:

You said our secrets kept us stranded. Somewhere else

there is a black box tossed in its wreckage, like a seed,

or polished stone. Somewhere else there is a sunken ship.

The wood is dissolving around the nails and rare coins.

They are like smooth, lidless eyes staring up from their depths.

On the shore there are wooden horses and hidden soldiers.

We find a number of objects vividly rendered—the black box, the seed, the polished stone, the decomposing sunken ship, the Trojan horses—that appear to play off of the “secrets” alluded to at the beginning. The black box of a crashed airplane contains the secret of what caused its demise; the seed conceals the blueprint of the plant it will be; the sunken ship holds a treasure; the wooden horses hide a contingent of soldiers. What the actual secrets are that these objects and their contents symbolize may not be known to us, but that may not matter; Minton’s accumulation of images raises the idea of concealment to a structural ideal through which we can—if we’re willing to–recognize the machinery of our own secret keeping.

As the allusion to the Trojan Horse shows, Minton’s poems are conversant with mythical motifs and themes. Consider the second poem, which in its entirety, reads:

I imagined that you had returned, as if from sea,

as the hippalectryon, the fire-colored horse-chanticleer.

When I stitched my mistakes into yet another monster,

you said it was fate, but you locked the tower gates.

You took my grief into a faraway kingdom, and built a room for it,

where impish creatures scratch the floor in the dark.

You placed a laboratory table, complete with straps

and elaborate equipment to measure every pulse and twitch.

You adorned the walls with your image, and routed our demons

with sunrise singing. You lined the village fountains with rare coins.

Your cults filled the temples. At home, citizens whispered

your secrets to each other. I will ask you to sing them to me,

later, while my eyes are still closed.

The overall theme seems to be of the return of a deity, which Minton lays out in images evoking Greek mythology and cult practice. The unnamed addressee is imagined as having emerged from sea in the form of a hippalectryon—an obscure creature half horse and half rooster mentioned by Aeschylus and Aristophanes, and which may have been associated with the sea god Poseidon. After an extended clinical metaphor on the purgation of grief, the poem returns to its main theme as the addressee is given a cult with dedicated temples as well as the ability to repel demons and bring prosperity, and to sponsor secrets that perhaps only initiates—the citizens whispering them—are privy to.

As recondite as Minton’s images and allusions can be, they never lose their footing in the world of immediate, personal experience. Here he relates a recollection of

…the wooden boat

where we spent a day in the summer.

It was like a toy in our enameled tub,

and you laughed at every wave that bumped it.

The comparison of the boat to an object as common as a toy gives the recollection a familiarity that is almost tangible. As Minton puts it at the close of the same poem, “Plato said to be on guard against this fiction./But the fiction is always there./My hands have touched its strange brick.” The mythical may intrude into the world and burden it with an ideal meaning, but the “fiction” of concrete experience is no less real for all that, and is never far away.

Four of the poems have their origins in actual, historical letters, which Minton has paraphrased, rephrased, and rearranged into second-order works. Wilfred Owen’s letter to his mother of 31 October 1918, written from a house near the Sambre-Oise Canal in northern France, originally was a chatty communication of news and (uncharacteristically) affectionate portraits of fellow soldiers, but Minton reworks it into a solemn incantation:

I will name this place from which I’m writing.

I will name it on a small sheet from a dark cellar in the forest.

I will name it while the smoke is thick and the ground is marshy.

I will name it after someone who appears at this distance.

I will name it as a gleam of white teeth, a wheeze of jokes.

I will name it with my ear glued to the radio’s receiver.

I will name it with the glimmer of the guns outside, the hollow sounds.

Minton’s transposition of the tone of the letter is entirely apt; as it turned out, this was the last letter Owen wrote. He was killed in an assault on the canal on 4 November, just one week before the armistice went into effect.

An enigma running throughout these poems concerns the identity of the “you” to whom many are addressed. Minton has described this person or persona as a “mythic ‘you,’” which I take to mean a cipherlike, perpetually indeterminate identity that stands as an open variable capable of taking whatever value we wish to give it. That at least seems to be the structural role that “you” is given to play. When Minton does fill in the variable, it often is in explicitly mythical or archetypal terms; in addition to being imagined as a hippalectryon and returning deity, “you” manifests itself as a “ghost,” “a girl among garlands,” a “mountain/rising thin and silver out of the water,” “an augur.” Like Rimbaud’s “I” Minton’s “you” is another, as it undergoes a number of metamorphoses while retaining its essential indeterminacy throughout.

As it happens, the elusiveness of the poems’ “you” opens up a broad field of play not only for the reader’s imagination, but for Magallón and Crouch’s evocative visual images. The images, which interpret the poems, alternate with the latter and incorporate fragments of Minton’s texts into their design. The images don’t illustrate the poems so much as they extend their meaning into another mode of presentation; by combining abstract forms with the human figure, as many of them do, they not only hint at the identity of the poems’ addressee(s) in any given instance, but strike a balance between the universal and the concrete that corresponds to the poems’ own balance between the mythical and the mundane.

◊

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).