On Russell Atkins: “Exteriors, Interiors”

Daniel Barbiero

December 2020

On Russell Atkins, Part 2: Exteriors, Interiors

Stimmung as Meaning

By his own assertion, Russell Atkins’ poem-objects are not themselves necessarily intended to communicate, at least not in the ordinary sense of imparting information separable from the language with which that information is communicated. But lack of communicative intent does not—and cannot—equate to lack of meaning. Meaning of some order is inevitable; once brought into existence these poem-objects find themselves not only situated within a world of meanings, but made of a material—language—that itself is inherently meaningful. The poem-object simply is meaningful on grounds other than those presupposed by the existence and sharing of indicative content. For Atkins, those grounds are aesthetic.

That Atkins intends his poetry to operate—to “mean”—aesthetically rather than discursively, with a language he calls “peculiar to itself” rather than with the plain, message-transmitting “language of common speech” is explicitly set out in his Manifesto, from which these quotes are taken. As he also declares there the aim of poetry and of art more generally is “largely AESTHETIC, not essentially information.” Paraphrasable content, to the extent that it exists, is not coextensive with poetic meaning; for the latter we need to look elsewhere. While this basic idea may be more-or-less a commonplace, the way that Atkins goes about embedding aesthetic meaning in language is his own. His poems often contain formal devices that separate them from ordinary language usages—for example, orthographic or grammatical displacements as well as unconventional arrangements of words on the page. But there is also something else, something more pervasive that emerges from the poem as a whole—as an integral object, we could say—and to which these different poetic devices may sum. That something is the atmosphere, or Stimmung, that the poem creates. Stimmung is a meaning, but not something intended to be transparently communicated as would, say, a statement in plain language; it may be, on the contrary, the product of language used specifically to avoid the plain statement and direct transmission of information. Looking beyond the specific case of poetry, we can say that as a general matter an artwork’s Stimmung, making itself felt through a complex of suggestion, indirection, oblique allusion, and associations made possible by the language or other material out of which it is made, creates a sense of mood and bypasses the plain communication of the purely indicative. Simply put, the work’s Stimmung is an event arising from the ascendancy of connotation over denotation. Any aesthetic object is liable to throw off a Stimmung simply by virtue of being an aesthetic object; how Atkins does it is a function of the idiosyncratic way he appropriates–and more importantly, disrupts—the linguistic medium.

The Seer

The poem Exteriors, Interiors, from Juxtapositions, gives condensed expression to an expansive atmospheric effect. The poem was inspired by the painting The Seer by Giorgio de Chirico; the poem itself seems not to be an ekphrasis or direct interpretation of the painting but rather a creative projection taking the shape of an imaginative scenario provoked by the painting. Not an appendage or an afterthought to The Seer but rather a counterpart to it—a complementary yet autonomous object bound to the painting through an affinity of affect.

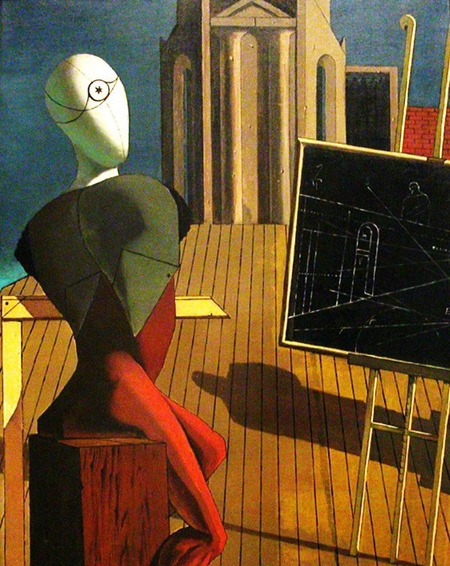

De Chirico himself was a painter for whom Stimmung was a supreme artistic value, particularly for the paintings of his metaphysical period, during which The Seer was created. Painted during de Chirico’s time in Paris just before the First World War the picture, like several other of de Chirico’s paintings from that period, depicts a mannequin—the seer of the title—in an ambiguous setting seemingly neither wholly indoors nor outdoors. Situated in front of the mannequin is a blackboard; on it are sketched in outline some of the objects from the iconography that appeared in de Chirico’s earlier metaphysical paintings. These objects, in a sense familiars of de Chirico’s, include an arcade, a statue seen from the back, a wall. In the background is a strange building with classical elements: a pair of Doric columns against a blind wall flanked on either side by an arch. Beside the arch to the right is a drawn curtain similar to the one that appears in The Enigma of the Oracle. Jutting out from the painting’s right edge is the shadow of what might be a statue on a plinth. Like de Chirico’s other exterior/interior paintings of the time, it shows a static scene. The moment it captures is immobile. A terminal stillness permeates this strange habitation of inanimate objects. What then does Atkins make of this, or rather, make out of it?

A Pervasive Uncertainty

Whether intended or not, the poem’s title—Exteriors, Interiors—is an indication of what is going on within it. Atkins takes the exteriority of the scene depicted in de Chirico’s painting and transposes it to the interiority of the poem’s speaker—to the speaker’s way of grasping himself within that scene. The scene permeates the speaker’s state of mind; the speaker’s state of mind permeates the scene: all of this crystallizes in the Stimmung of the poem, which in turn is elucidated in Atkins’ dislocations of diction and grammar.

At the outset, Atkins obliquely introduces a scene of quiet and solitude—of “this place that wishes to be left/to its own devices” which is “awhiled with wan, long-length’d.” This is no description of a location in terms of its observable qualities alone—of the qualities one sees, but rather of the qualities one sees in it or, better yet, sees into it. We get an indication of this in Atkins’ strange construction “awhiled,” which together with “long-length’d” connotes a place extended in time or through time as experienced qualitatively by the speaker, rather than a place measured in physical distance. It is a place where a “long-length’d” period of time has gone by, perhaps as represented by the lengthening shadows so often encountered in de Chirico’s metaphysical exteriors and encountered in The Seer in the shadow projecting in from the picture’s right edge. The speaker has been here a while, long enough to experience the shadows creeping slowly at a feeble, “wan” pace. This is a place, in sum, of affective engagement, where length is measured in the subjective sense of time’s passage, of its moving weakly. And yet somewhat ominously as well. For the speaker, this place is shot through “with the solemnity of loomed/footfall’d.” The strangeness of this characterization, which implies much but divulges little, is codified by the linguistic structure Atkins uses–one which ends abruptly with “footfall’d,” a dangling construction apparently of Atkins’ invention and certainly of his mannered spelling. It is an odd coinage that, like “loomed” just before it, seems to function as an adjective but which has no noun attached to it. The absence of a noun here creates the sense of something hidden, something hinted at but not there. The missing noun is a trace, but a trace of what? It is only at the end of the poem that the non-presence the absent noun reveals in its absence will present itself.

The second stanza brings in the speaker, who appears to be an observer of the scene and of the something there that seems not to be there. He is present to a presence that remains out of view—“the one/out and out/who is not seen”—and yet is felt just beyond the edge of what can be physically perceived. It’s a strange mode of being–a presence ostensibly poised in the exteriority of the surrounding scene yet known only through its position within the interiority of the speaker’s affective state. In addition, this strangely liminal presence—perhaps because it is liminal, because it is felt and not seen–provokes a mood of self-doubt within the speaker. It is a mood that Atkins emphasizes by using, three times, the word “certain”—as a kind of thesis (“I’m certain”), answered by an opposing antithesis (“not being certain”) that leaves the speaker with a non-synthesis suspended within a counterfactual:

…If I could enter now

behind the arch, for example

(the where

the one watches) I feel as certain as I am

leaning…

(Even the basic device of lineation takes on aesthetic import and contributes to the Stimmung of uncertainty. Here and throughout the poem the lines stagger down the page in a seemingly arbitrary manner, suggesting the footfalls of someone on an uncertain footing.)

Atkins’ construction “the where” here is anomalous—an apparent case of elision in which a noun phrase is missing its noun. One would normally expect to find a word like “place” between “the” and “where” here, but like the presence the speaker feels, its appearance is as a non-appearance. It is another absence that serves to contribute to the overall mood of uncertainty. Where we would expect to find the word “place” (or something similar to it) we only find “where,” which in the absence of a concrete indication of place seems to become the unanswered question—“where?” The fact of place itself is displaced here, removed or never there, an exterior rendered atopos—strange, out of place–through the speaker’s interior transformation. If “long-length’d” refers at least in part to the shadow cutting across the scene it is applicable not just to a literal shadow thrown off by an object blocking the light but to the shadow of doubt that seems to enfold the speaker.

And Yet a Paradoxical Certainty

As noted above, it is only at the end of the poem that Atkins gives thematic, if not grammatical, closure to the dangling construction “footfall’d.” We learn that it is the “one who is not seen/who/footfalls.” This someone unseen may be someone only imagined, someone non-existent in fact—no more substantial than the creeping, long shadow by which the speaker’s sense of time is measured. As with many of de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings, Atkins’ poem implies a presence that makes itself known only indirectly, through oblique clues and traces, which here seem to take the form of the sound of footsteps. And also as with de Chirico’s paintings the presence’s apparently not being there is an index of its in fact being there; the footfalls the speaker hears, or imagines hearing, are pure contingencies, possibilities made possible by the transposition to an interior key of the enigmatic world de Chirico painted—a world in which non-being, in the guise of the flux of becoming, is Being’s most convincing alibi. It is a necessarily ambiguous alibi, though, precisely to the extent that it is grounded in the possibility of the non-being of Being. Confronted with it, one is always and inevitably “certain of not being certain/that there is someone” there. That there is anything there, or that anything was there or could be there at all. It is this paradoxical certainty grounded in uncertainty that Atkins’ Exteriors, Interiors communicates—perhaps unintentionally, but nevertheless it does communicate–by aesthetic and non-indicative means. Through the Stimmung it discloses.

Exteriors, Interiors from the book Juxtaposition by Russell Atkins →

On Russell Atkins: The Poetics of Objectified Mind

Read Part 1 on Arteidolia→

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places & Wooden Mirrors with Cristiano Bocci and In/Completion a collection of verbal and graphic scores by composers from North America, Europe and Japan, realized for solo double bass and prepared double bass.

More by Daniel Barbiero on Arteidolia →