WAAVe Global Gallery Women Asemic Writers & Visual Poets: The Pure Mark of an Event

Daniel Barbiero

March 2022

Asemic art drives grammatology to its most paradoxical extreme. The marks in an asemic work seem to be some variety of writing, whether alphabetical or idiogrammatic, but a writing deliberately devoid of intended meaning, hence the name “asemic.”Asemic grammatology is thus always a simulation of grammatology, an interpretation of meaning grounded in an eidolon or phantom writing substituting for or supplanting the real thing. Asemic grammatology may involve the hunt for meaning that isn’t there, but because asemic works by default or design exploit the natural human tendency to interpret signs—especially signs that appear to be language—they inevitably mean, albeit in a way that takes us beyond reference and into the deeper implications of language as a material medium with an appearance, a history, and an existential function. Asemic works mean in spite of themselves, and because of themselves. And as demonstrated in WAAVe Global Gallery Women Asemic Artists and Visual Poets, an anthology of work by an international sampling of women artists active in the field of asemic art, they may mean in a variety of different ways.

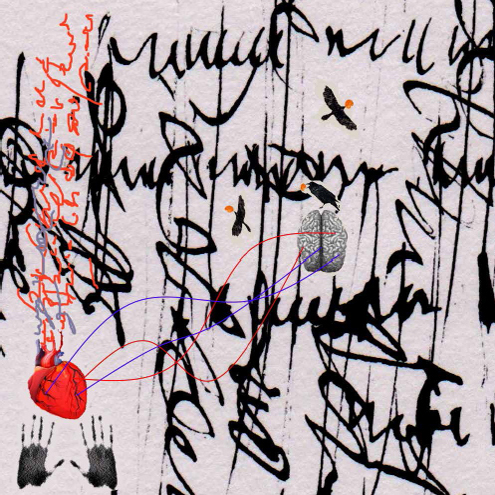

Satu Kaikkonen

Satu Kaikkonen

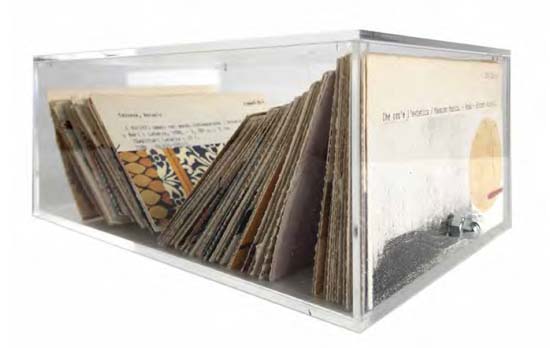

For this richly illustrated and substantial volume, managing editor Kristine Snodgrass assembled a group of thirty-eight female artists of varying backgrounds currently living in Europe, Asia, and North and South America. The book is laid out in seven thematically organized sections, each of which was curated and introduced by one of Snodgrass’ co-editors; each section contains the work of several artists, followed by the essay “Bhubezi Women Writing System,” by Cheryl Penn. The thematic sections–“Writing and Silence”; “∞”; “Collaboration”; “Color”; “Their Mortal Touch”; and “Remembering and Forgetting: the Care Takes Place”–offer different conceptual points of entry for looking at and responding to asemic work.

Nicola Winborn & Rosalie Gancie

Nicola Winborn & Rosalie Gancie

One of the pleasures to be had in looking through the individual pieces in the volume is seeing the different ways their affinities cut across its given themes. For although the art and artists presented here represent a true, and truly astonishing, diversity of styles, media, and purpose, they all share a connection to language that is both allusive and elusive: allusive in their hinting at the forms and functions of language, and yet elusive in that throughout all of these pieces language’s main practical function—to express and convey intentional meaning, to refer to objects, events and states of affairs—always hovers tantalizingly out of reach. Always hovers over the abyss of an articulate silence.

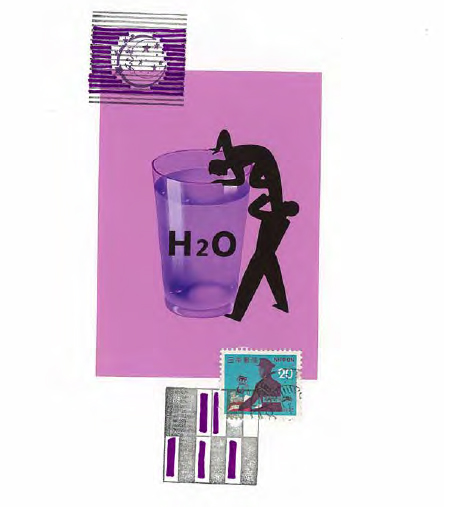

Camela Corsitto

Camela Corsitto

In fact, in the introduction to “Writing and Silence,” fittingly enough the opening section, Cinzia Farina, the section’s editor, sets out what could serve as the general conceptual framework for the collection by evocatively describing asemic writing as a “non-verbal writing that…becomes a space of silence.” For Farina, it is a silence that removes language from the distractions of the “overflow accumulated in the ordinariness of languages.” What she describes is a communicatively uncommunicative silence that I would gloss as consisting in a boiling off from the sign its capacity for signifying a specific, intended, and by implication, mundane reference, leaving it as the pure mark of an existential moment that is an event in and of itself, an event that may signal “there is language going on here” and nothing more. But that nothing is itself a potential opening of its own—an opening not only to the possibility of a human encounter taking place on the ground of language, but an opening to those dimensions of language that escape the immediate work of reference and establish themselves as attention-worthy in their own right.

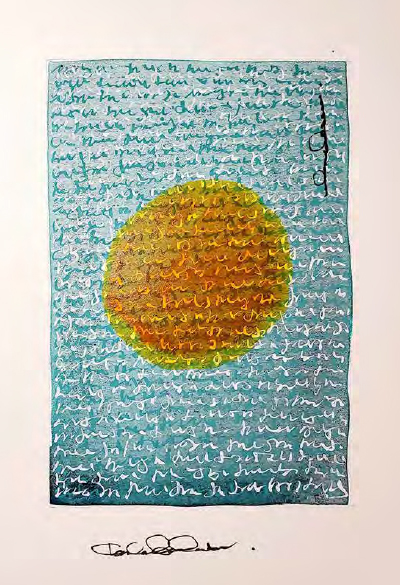

Fernanda Fedi

Fernanda Fedi

But to begin with silence. Carmela Corsitto’s two untitled works dramatically capture the sense of language emptied out and made mute. Each consists of an object that resembles a time- or weather-warped book whose pages, made up of white plexiglass, are blank. Language is present here by implication, either as something latent and as yet to be made explicit, or else as something removed through erasure; language before the alpha or after the omega, the sign of speech at that concrete moment when it is about to emerge from or dissolve back into silence. If Corsitto’s work seems to subtract language from itself at the terminal points of its articulation, Catherine Vidler’s two pieces seem to advocate dismantling language at the atomic level by pointedly disassembling the word “syllable.”

Tomasina Bianca Squadrito

Tomasina Bianca Squadrito

While Corsitto’s and Vidler’s pieces direct attention to the existential and elemental origins of language, other works allude to language origins from a historical perspective. Fernanda Fedi, like Corsitto one of many Italian artists represented in the book, creates work containing scatterings of signs taken from the ancient Etruscan alphabet, one of the earliest in use in what is now Italy. Her two contributions look as if they could be contemporary analogs of the Marsiliana Tablet. In another historically-inspired gambit, “The Letter Is the Bookworm of the Letter,” a piece by Helena Trindade, takes pages from an etymological dictionary, twists them, and overlays them with chains of metal type heads broken off from the bars of an old typewriter. Through a kind of recursive positioning of letters within letters, the antiquated meanings of words are provocatively juxtaposed to an antiquated writing implement. There also are pieces that seem to reach back in time beyond language to the pre-linguistic significations of cave painting. Satu Kaikkonen’s “If I Lost My Mind My Hearth Will Remember” contains handprints and images of birds, a heart and a brain that wouldn’t look out of place on a wall in Lascaux, while Lova Delis’ delightful blue-and-green composition “After Kundalini” features black linear forms that seem to want to coalesce into stylized, archaic figures.

Kiki Franceschi

Kiki Franceschi

Several artists’ contributions foreground the aesthetic dimension of written language—the shapes and visual rhythms made by letters and words, real or invented, arranged on the page. We can see this in the way the quasi-script in Kiki Franceschi’s stunningly beautiful blue piece mimics the cursive flourishes of a fine 18th century hand, or in Kavitha Balakrishnan’s “Match-box Poems” with their drawn, rather than written, Malayam script. In one of the book’s collaborative efforts, Snodgrass and Karla Van Vliet present a quasi-Arabic or Farsi text turned sideways.

Karla Van Viliet & Kristine Snodgrass

Karla Van Viliet & Kristine Snodgrass

Linda Stern’s “Sound Clouds” depicts the tight, neat lines of words in an unknown alphabet emerging from a billowing shape of vivid colors, while Eugenia Di Meo’s piece made up of cascading, broad brushstrokes evokes calligraphy in the style of classical Chinese ink wash drawings. Randee Silv’s two energetically contrapuntal compositions of thick and thin black lines take the idea of calligraphy to its roots, suggesting with an intense immediacy the physical gestures that produced them. In “Il pleut 19,” a calligram by Amaranth Borsuk and Terri Witek, alogically sequenced words fall like typeset rain down the page.

Appropriately enough, language cannot adequately capture the provocative beauty to be found in WAAVe Global Gallery Women Asemic Artists and Visual Poets. It has to be seen for itself.

Antonella Cuzzocrea

Antonella Cuzzocrea

For more information about WAAVe Global Gallery →

◊

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).

More by Daniel Barbiero on Arteidolia →