Barnett Newman and the Sublime

Daniel Barbiero

September 2023

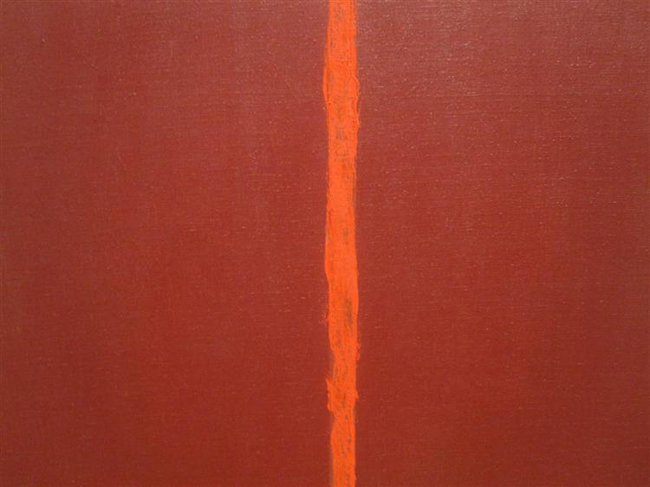

Onement III, Barnett Newman, 1949

Onement III, Barnett Newman, 1949

The route to Barnett Newman’s notion of the sublime runs through Jean-François Lyotard. In “The Sublime and the Avant-Garde,” his essay on Newman’s painting and sculpture, Lyotard in effect asks how, in light of Newman’s work as well as his programmatic statement “The Sublime Is Now,” we are to conceive of the sublime. Lyotard suggests that the sublime is a complex experience centered on the material in which the artwork is embodied — a material that in its sensuality resists assimilation to thought and the latter’s generalizing translation of the concrete particular into the universal Idea. While this is an important theme in Lyotard’s thinking, and one with obvious relevance to how a painter would confront and express the sublime, I want instead to focus on a second theme. This second theme is directly relevant to Newman’s notion of the sublime as well. For as we will see Newman, like Lyotard, ultimately understands the sublime as an event, a revelatory happening that takes place in a given moment at the edge of intelligibility. In short, to find the sublime, we must look to the “now.”

Lyotard Reads Newman

It is precisely the “now” of Newman’s “The Sublime Is Now” that Lyotard finds provocative. As he asks in his essay on Newman, how are we to “understand the sublime…as a ‘here and now’?” (Benjamin, p. 196). This is the question that, in essence, concerns Lyotard. Seemingly, a simple question, but one that inevitably ramifies into a complex of related questions: what exactly is the “here and now,” what constitutes it, what does it give rise to or, alternately, what takes place within it? And what is the nature of the sublime, given that it arises in some kind of field of immediate experience? Avoiding a simple answer, Lyotard rejects the notion that Newman’s “now” is a “present instant.” Rather,

Newman’s now which is no more than now is a stranger to consciousness and cannot be constituted by it. Rather, it is what dismantles consciousness, what deposes consciousness, it is what consciousness cannot formulate, and even what consciousness forgets in order to constitute itself. What we do not manage to formulate is that something happens…Not a major event…not even a small event. Just an occurrence. (Benjamin, p. 197)

Lyotard continues by holding that such an event is “infinitely simple” and cannot be thought; in addition, it carries with it a sense of suspense. Something happens, but that something is indeterminate, indefinite. A particular kind of suspense, the suspense of anticipation, is what defines the event in its essential ambiguity and shapes the way we experience it, most noticeably on an affective level. It may bring anxiety, but just as well may bring the pleasure of an expectant hope before the unknown. Lyotard argues that it is this “contradictory feeling” that 17th and 18th century European philosophy “christened…by the name of the sublime” (Benjamin, p. 199).

As a consequence of its essential indeterminacy, Lyotard holds that the sublime consists in the “inexpressible” which is a correlate of the unthinkable moment whose – necessarily inarticulate – meaning can be paraphrased as “that (something) happens” (Benjamin, p. 199). Put another way, that something happens, that there is an event, is inexpressible and hence sublime. The artwork presumably provides the occasion for this event and thus creates the conditions under which the inexpressibility of the event can make itself felt; this latter occurs in a displacement of thought, an evasion — perhaps a momentary evasion, arising at the point of encounter with the artwork? – of the ability of the mind to effect a conceptual capture of the event. The upshot of this is that the suspension Lyotard is getting at is not to be thought of as a temporal suspension per se — it is not the sense, however fugitive, of a stoppage in time – but rather consists of a suspension of intelligibility. For as he suggests, the sense of the sublime involves

Letting-go of all grasping intelligence and of its power, disarming it, recognizing that this occurrence [of the artwork] was not necessary and is scarcely foreseeable, a privation…guarding the occurrence ‘before’ [thought can grasp it]…It’s still the sublime in the sense that Burke and Kant described and yet it isn’t their sublime any more. (Benjamin, p. 199)

Robert Baker, I think, said it most economically when he summarized Lyotard’s position as holding that the sublime consists in “a presentation of the unpresentable, or…a presentation of the fact that the unpresentable exists.” As such, the sublime is “testimony to an ‘absolute’ or an ‘infinite’ that eludes positive representation or clear and distinct conceptualization” (Baker, p. 70). The experience of the sublime, in other words, brings us into an intuitive, inarticulate contact with something that carries the weight of meaning of the absolute, or the existential ultimate.

Newman Experiences the Sublime

Newman’s own thinking on the sublime was suggestive rather than systematic. It finds its most direct expression in the statement “The Sublime Is Now” of 1948, and most forcefully, if not explicitly named, in the notes published under the title “Ohio, 1949.” By looking at both, I believe we can get a good idea of what Newman meant.

In “The Sublime Is Now,” Newman claimed that American art could realize the sublime by leaving behind the inherited constraints — the “impediments,” as he put it – of European art’s preoccupation with figuration and the question of the nature of beauty. In his opinion,

the failure of European art to achieve the sublime is due to [its] blind desire to exist inside the reality of sensation (the object world, whether distorted or pure) and to build an art within the framework of pure plasticity…[through which it] became enmeshed in the struggle over the nature of beauty; whether beauty was in nature or could be found without nature. (Shapiro and Shapiro, p. 328)

The thrust of Newman’s argument seems to be that European art went wrong when it attempted to reach the metaphysical through the portrayal of the physically beautiful — the latter itself counting as a contested and contestable ideal whose source or embodiment could be said to lie in nature or could be contrived artificially — by way of the human-created object. As he expressed it, “Man’s natural desire in the arts to express his relation to the Absolute became identified and confused with the absolutisms of perfect creations…” (Shapiro and Shapiro, p. 325). When the path to the sublime is conceived of as running through the materially beautiful, Newman seems to imply, it can only culminate in an empty cul-de-sac.

If not in the physical features of nature or in crafted objects, where then to look for the sublime? I believe tht Newman provides the answer in “Ohio 1949.” These notes, an early draft of which carried the title “Prologue for a New Aesthetic,” seem to have been intended as part of a programmatic statement of artistic principles. Their focus, notably, is on Newman’s own experience of the sublime – although he doesn’t call it by that name – while visiting the pre-Columbian mounds and earthworks of the Ohio Valley in August 1949. Newman described these artifacts as “the greatest works of art on the American continent…[and] perhaps the greatest art monuments in the world” which he thought embodied “the self-evident nature of the artistic act, its utter simplicity.” This latter wasn’t the subject of the earthworks, or something that could be reproduced in a photograph; instead, what he felt was at stake was “a work of art that cannot even be seen,” but had to be “experienced there on the spot” (Newman, p. 174). What was this invisible, intangible something that produced such a sense of awe in him? As he described it subsequently in conversation, it was the sense of his own presence, of “Here I am, here” (quoted in Hess, p. 73). But this wasn’t about space, of Newman finding himself situated in a particular place, even if a particular place was the provocation for the experience. Rather, what Newman felt was what he described as the “sensation of time – [in which] all other multiple feelings vanish like the outside landscape” (Newman, p. 175).

It seems to me that what Newman recorded in “Ohio 1949” is nothing less than an encounter with time as it is experienced concretely — I would go so far as to say, existentially. Here is how he described it:

Only time can be felt in private. Space is common property, only time is personal, a private experience…The concern with space bores me. I insist on my experiences of sensations in time — not the sense of time, but the physical sensation of time. (Newman, p. 175)

This physical sensation of timeproduced in him a state of mind — or perhaps something more, better described as a state of being – in which everything associated with that moment was enveloped and dissolved.

How exactly what Newman calls “the sense of time” is to be distinguished from “the physical sensation of time” Newman doesn’t say. But we can conjecture that the former consists in something like the ordinary sense of time as we experience it in the flux of before-and-after, or more prosaically, in our awareness of the passage of minutes and hours. Whereas the latter involves something more immediate. When we take into account Newman’s later remarks, it would seem that the physical sensation of time involves something like an event of pure presence to self, a moment whose meaning lies entirely in an intuitive self-awareness in which the experience of oneself is as the “here” through which the world manifests itself — a “here” that is exchangeable into the currency of the “now.” And the “now,” for its part, is a moment of absorption in the moment, in which the moment alone makes itself felt as the opening through which one intuits one’s own presence. The “I am” of “I am here” vanishes into the “here;” it becomes the “here” to the extent that it is intuited in the guise of the “now.”

How does this compare to the “now” of Newman’s “The Sublime Is Now”? It seems to me that this latter is something altogether different from the sensation of time as Newman felt it in the Ohio Valley. Rather, the “now” of “The Sublime Is Now” seems to refer to the historical moment of postwar American art’s usurping the place of European art as the paradigmatic expression of Western aesthetics. This “now” is the moment when American painters eclipse their European counterparts in creating an epochal art; it is a historical “now,” as opposed to the concrete, individual, and existential “now” Newman seems to have experienced during the Ohio Valley visit. The sensation of time constituting the Ohio Valley “now” would appear to be a “now” out of time as we ordinarily inhabit it.

It seems to me that we can draw a parallel between Newman’s “physical sensation of time,” in which one intuits oneself as the “here” as it is absorbed into the “now,” and Lyotard’s anticipatory sense of the “now.” Both Lyotard and Newman locate the sublime in something momentary; for both, it is an event. For Lyotard, as we have seen, this is an occurrence of the inexpressible that is itself indeterminate but is grounded in the anticipatory sense of something being about to happen. For Newman, it is the “now” that he seems to equate with the physical sensation in which “now” is experienced as that “here” in which one simply is. Perhaps we can look beyond their differences of terminology and read both as hinting at the same thing: an inarticulate event of pure presence that is not to be confused with the present considered as a moment in time. For both, it would seem that the temporal present is simply an index, a pointer indicating the event or happening that takes place, and is experienced, in that moment. The “now” of time is, to borrow the old Zen image, the finger pointing to the moon which is not to be confused with the moon itself. And the “moon” here is the event, the happening, the occurrence, associated with the moment. What then is that event? I believe we can start to get an answer by exploring some of the implications of the experience of pure self-presence.

The Concrete Moment and Pure Self-Presence

The physical sensation of time is the experience of the present as a concrete moment — a moment whose concreteness lies in the experience of its contingency. This experience doesn’t consist of the sense of finitude that arises from a general reflection on one’s place within time — on the considered awareness of one’s necessarily limited lifespan bounded on one side by the nothingness of a time when was not yet and on the other by the nothingness of a time when one no longer is — but rather arises from, or better yet, accompanies, the unself-conscious awareness riding the surface of the aggregate of sensations and perceptions that mark each moment as this moment now, and no other. Upon reflection, the present may be conceived of as the vanishing point where past and future meet, but as lived in its unreflective immediacy, it is simply experienced as the “there is” of this given moment, with its temporary equilibrium of sensation, thought, emotion, perception, and so forth. It is the “now” as the “there is” of pure self-presence.

What I have described as the concrete experience of the moment would seem to have points of contact with Lyotard’s notion of the present that resists presentation. Consider that as Lyotard would have it, the present that resists presentation is unpresentable because it is indeterminate. The quality that Lyotard finds in the unpresentable present – its indeterminacy — is indeed a quality of the kind of concrete self-presence that is the “there is.” It just seems to be so that the experience of pure self-presence, in its immediacy, is indeterminate because it represents a pre-personal mode of being that hasn’t yet been differentiated into subject and object, or hasn’t crystallized into an “I” with a distinct identity. It is an originary mode of self-givenness in which there isn’t yet a question of a “self” per se. To the extent that it remains at this level of self-presence, its occurrence evades conceptual capture and representation. It is a mode of experience prior to thought and expression. Rather, it is something that is inhabited.

Pure Self-Presence and Availability

The sensation of pure self-presence with which the physical sensation of time is bound up is not just any presence, but a presence that is simultaneously bodily and sentient — a presence that isn’t known so much as intuited or felt through the sensation of movement, of stillness, of the heaviness of the matter that I grasp as myself even before there is any proper sense of “I” or “myself” as a determinate being. In fact, pure self-presence is to that extent a self-presence of the emptiness of the self as such. There is only body-and-the-awareness-of-the body, before body and awareness separate themselves out into different realms given as objects of reflection – just the inhabited and felt, rather than known, sense of being the site at which movements, sensations, perceptions, and so on originate and converge. This experience is something prior to the experience of oneself as divided into mind and body; it is the experience of embodied mind or mindful body, a kind of sentient thingness or thingly sentience that exists outside the limits of the self properly understood. The experience of pure presence associated with this bodily sentience is simply the sentient body’s grasp of itself as itself, prior to the specific determinations that individuate it as a self proper — a self that recognizes itself in the personal history and enduring identity of which it is reflectively aware. It isn’t the grasp of oneself as an “I” with a particular content — a particular history, a collection of likes and dislikes, of needs and desires and so forth — but rather the inarticulate sensation of “there is,” of being or occupying a “there” through which things and others can make themselves known. It is a pre-personal mode of being, prior to the consciousness of oneself as having certain determinate characteristics and qualities. It is as if one were an open variable waiting to take a fixed value.

This pre-personal, bodily-sentient sensation of presence to self is the originary sensation of availability to the world and the entities, events, and situations that make up its furniture. It is originary because it stands at and as the origin of any determination it may take on relative to itself or to the things and others around it, and of any determination that those things and others may take on in turn. It is the intuition that “I,” in the guise of this entity yet without qualities, exist, and that “my” self-presence is something that is in fact present. I put the first-person pronouns in quotation marks here because at this moment there is no question of “my” being the “I” that I recognize as an aggregate of qualities; the “I” of this moment of sensation is simply the brute existence of a purely pre-reflective intuition. It is an intuition that finds its expression in the unthematized sensation of oneself as an opening, as a presence opening out to the presences among which one finds oneself.

The Intuition of the Sublime

But to return to the physical sensation of time. It is the concrete moment as a facet of that intuition of one’s existence in its originary mode of self-givenness. It is an unpresentable present to the extent that what constitutes it is the pre-personal mode of pure, and hence empty, self-presence. This unpresentable present — the moment of self-presence in its indeterminacy — is in effect the moment of existence laid bare in its essential gratuitousness. And it is from this sense of gratuitousness that the sense of the sublime arises. What is sublime about it is that it is the — once again, inarticulate and simply intuited — sense that there is something rather than nothing and that this something is in fact oneself. Put another way, it is one’s existence felt in its gratuitousness and sensed as the brute thatness of one’s being here where otherwise there would be nothing. What makes this existence – of which the concrete moment provides an intuition — give itself as gratuitous is the sheer audacity of the fact that it is there. It is intuited pre-reflectively – we might say “unconsciously” – against the background of a nothingness that it displaces. This point is worth emphasizing—that the intuition is a mute one, something felt rather than known, something that only subsequently can be articulated and made present in determinate form.

The brute fact of there being something rather than nothing is something without justification or alibi but is simply there, in the plain fact of its being: this something very well did not have to be. That there is something rather than nothing is an intuition of the sublime because it is overawing and abyssal, a perspective opening out over the void that is the nothingness it very well could have been. As befits the sublime, this is an intuition that pushes up against the limits of imagination to the extent that, because one is, one cannot really imagine the experience of what it would be for there not to be at all. One can approach it only indirectly, though the recognition that there is something when and where there need not have been, and that that something that need not have been is oneself, that “self,” in its emptiness, that is simultaneously both the point of origin and the point of convergence of sensation. Of the very sensation that senses itself as here, now: as that point at which, as Newman put it, “all other multiple feelings vanish” because it is that gratuitous presence to which all else is available to be present, because it itself is available to all else.

To locate the root of the sublime in the mute presence to self that is intuited as the brute thatness of an embodied mind and mind-pervaded body is to strip the sublime down to the primordial experience that makes it possible — to the originary sense supporting the intuition that one simply is, when in fact one need not be. To this intuition, this point from which the sublime appears and into which it vanishes, the raw fact of existence itself is sublime. It is this basic and original sense of awe that lies at the root of the subsequent experiences of awe that we call “sublime.” It serves as the paradigm and template for what we feel – perhaps as an echo – when in the presence of a breathtaking landscape or an affecting work of art. And where the sublime ends, perhaps the marvelous begins.

References:

Robert Baker, The Extravagant: Crossings of Modern Poetry and Modern Philosophy (Notre Dame IN: U of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

Jean-François Lyotard, “The Sublime and the Avant-Garde,” in The Lyotard Reader, ed. Andrew Benjamin (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989). (Online at https://www.artforum.com/print/198404/the-sublime-and-the-avant-garde-32533)

Barnett Newman, “Ohio 1949,” Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews (New York: Knopf, 1990).

______________, “The Sublime Is Now,” in Abstract Expressionism: A Critical Record, ed. David Shapiro & Cecile Shapiro (Cambridge: Cambridge U Press, 1990).

◊

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer, and writer in the Washington DC area. His reviews of poetry and essays have appeared in Heavy Feather Review, periodicities, Word for/Word, Otoliths, and Offcourse. He also writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century as well as on contemporary work. His music reviews have been published in Perfect Sound Forever, Point of Departure, Avant Music News, and elsewhere. Barbiero has performed at venues throughout the Washington-Baltimore area and regularly collaborates with artists locally and in Europe. His graphic scores have been realized by ensembles and solo artists in Europe, Asia, and the US. He is the author of As Within, So Without, a collection of essays published by Arteidolia Press.