Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty

Colette Copeland

November 2023

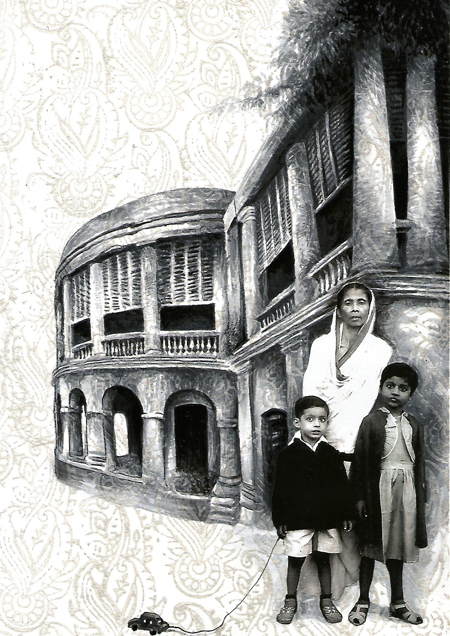

Homeland-III (2018) Collage & Acrylic on Fabriano, 9×11 inches.

Homeland-III (2018) Collage & Acrylic on Fabriano, 9×11 inches.

Curator Lina Vincent suggested I contact artist and Amity University Professor Moutushi Chakraborty. After contacting her via social media, (Instagram seems to have replaced business cards completely) I realized we shared another artist connection—Annu Matthew, an Indian American artist who teaches at the University of Rhode Island.

This interview comes from a series of conversations that Moutushi and I had over tea in her studio at Newtown, on the eastern fringes of Kolkata. We discussed the challenges for Indian female artists. Despite the fact that the majority of art students are female, very few teach at upper-level institutions. When a woman marries, the art world dismisses her commitment to art and when she has children, her status is further diminished. Although many galleries are owned by women, male artists dominate the gallery roster. These are primary reasons why I focused my Fulbright research on female artists.

Colette Copeland: Using a variety of printmaking processes, your early work challenges the representation of women in art and in contemporary culture, as well as explores violence against women. In graduate school, you began exploring historical archives as source material to examine the colonialist gaze, as well as using the self as a surrogate to question identity and the authenticity of history. How has your work evolved both conceptually and materially, since the early archive work?

Moutushi Chakraborty: My reference into archival photographs of Colonial India began in 2001, after viewing the exhibition ‘India: pioneering photographers, 1850-1900’ at the Brunei Gallery of SOAS in London. While exploring the archived photographs at OIOC (Oriental and India Office Collection) at the British Library, I was struck by the marked absence of photographic records of middle-class women in the collection. Photography came to India at a time when women were not allowed to come out in the presence of men, as per the strict social system of Purdah (seclusion). The early photographs of indigenous women were either social outcasts like the Nautch women (music and dance performers) or Royal heads who were empowered enough to face the camera upfront, fashioning themselves after Empress Victoria.

Thereon the history of photography coincides with the narrative of feminine empowerment in this nation. My attempt has been to investigate these narratives and their varying identities, irrespective of sociological hierarchies, as seen in the Identity as Illusion series (2001-02); a set of screenprints, wherein I masqueraded as different characters. The role play ranged from reticence to empowered posturing, often photo montaging into actual 19th century photographs, to question the legitimacy of crude patriarchal assumptions on morality.

After this early body of work, my life as an artist went through a drastic change of events including multiple relocations, motherhood, challenges of gaining access to archival materials in India and finding means to support my studio practice. The difficulty of accessing archival materials could be resolved through references into online digital archives, alongside surveying of family albums of acquaintances and collections from flea markets. Conceptually my focus continued towards enquiring the positioning of indigenous women, from a Colonial past into the Post-Modern era.

My search centered around the transmutative journey of women as they embraced modernity into the conservative folds of their lives to become part of a global shift towards emancipation. Conversations-I (2016) was a screenprint created more than a decade later, addressing the fascination of the ‘other’ (body color and attributes) among women. It presents a fictionalized image of an actual conversation between Queen Victoria and the Indian Royal Maharani Suniti Devi, complimenting each other and exchanging skin-care potions.

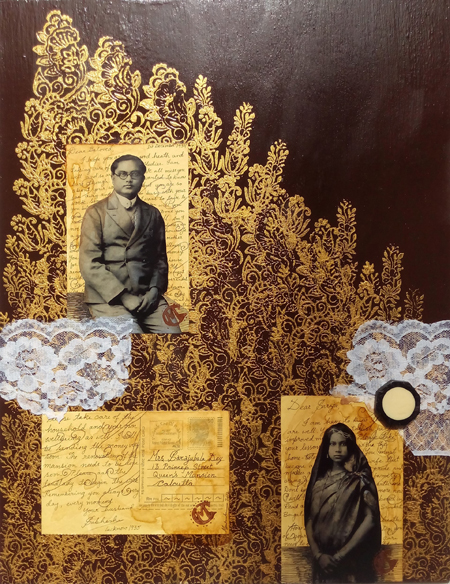

Memoirs as Letters-V (2018) Collage, Ink, Acrylic, Button &

Memoirs as Letters-V (2018) Collage, Ink, Acrylic, Button &

Cotton Lace on Postcard pasted on Plyboard, 18 x 14 inches.

CC: As you know, my Fulbright research centers on the themes of borders and boundaries. In the two series, Memoirs as Letters (2017) and Homeland (2018-2019), you probe various types of boundaries—geographic, psychological and temporal. Using your grandfather’s postcards sent by his family in Bangladesh, while he studied in India as source material, Memoirs as Letters explores family history through the lens of migration. Homeland addresses the vanishing historic residential architecture in India. How do the themes of borders intersect in these two bodies of work?

MC: My family, like many others, bears the legacy of the 1947 Partition of India. The term ‘border’ therefore remains poignantly relevant for me, even after 76 years of independence. The horror and trauma of forced exodus remain immortalized through personal anecdotes shared from generation to generation, as testament of insignificant people who survived the significant trials of human atrocity. Post-migration ordeals were no less traumatic for families as they raised questions of dignified identity.

Memoirs as Letters (2018) was a series prompted by postcards written to my grandfather by his parents from across the border. Built out of fictionalized postcards written between family members, the series crystallizes the preciousness of relations against parallel adversities of time and geographic borders. The Homeland series (2018-19) addresses migration of a different sort, one that is more psychological, leading to the voluntary migration of people leaving behind ancestral homes in their desire for a better life. To preserve these architectural marvels of olden times, I created this series of homes as memorials of people lost in time.

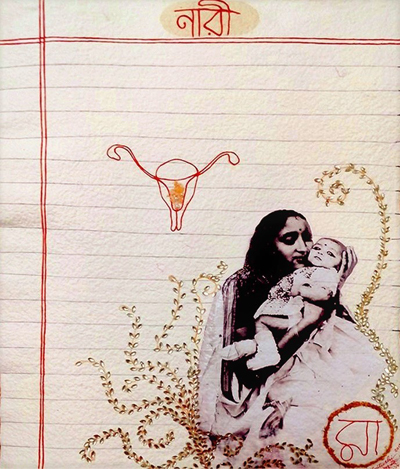

Aurat-VI (2018) Cotton-rag Pulp, Thread, Collage, Rose

Aurat-VI (2018) Cotton-rag Pulp, Thread, Collage, Rose

Pollens, Glass & Pearl beads, 18 x 22 inches.

CC: How does the incorporation of mixed media inform the context of these works?

MC: I believe femininity is best expressed by ‘personal touch’ – one that weaves meaning into materiality and thereby creates an inclusive experience incorporating a myriad of elements that may be varied but certainly not random. As a printmaker, I often question the very limited idea of printing with the purpose of editioning and hence have moved on to include drawing, collage, fabric, embroidery, threads, seeds etc. The idea is to evoke an essence of familiarity, one that transforms the mundane into a relic of timeless memory.

CC: Two recent series, Aurat and Mendings embody challenging personal experiences into the work. Please briefly explain the two projects and how the work has brought about catharsis and closure.

MC: Aurat meaning ‘Woman’ was a series that I worked on from 2016 to 2019. Made entirely with cotton-rag pulp, collage, threads, bead etc. the series strives to explore the notion of femininity from an elementary level, contextualized by the textbook format that acts as a background for each piece. The images, sourced from personal family albums and other resources, bring forth the essence of femininity, imperfections included, that become part of its iconographic narrative. It embraces the youthfulness of femininity as much as its maturity, acknowledges varying shades of skin color as nothing more than diverse perspectives, rejoices in subversion of the empowered, while cherishing the tenderness of familial bonds like motherhood. The catharsis of emotions embodied in this series corroborates with gleanings of personal narratives. It has always been my objective to create a discourse between the personal mundane and the universally significant. A more recent work Mendings (2023) achieves this objective by speaking of closure that is both personal as it is universal, through the simple act of stitching together blood-red pieces of fabric on a sewing machine.

Moutushi Chakraborty, Instagram →

Moutushi Chakraborty, Homeland, hakara: a bi-lingual journal of creative expression →

This is the sixth in a series of interviews Colette Copeland will be doing as part of her Fulbright Research Award to India. Her research focuses on socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

◊

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.