Metzinger’s Cup

Daniel Barbiero

January 2024

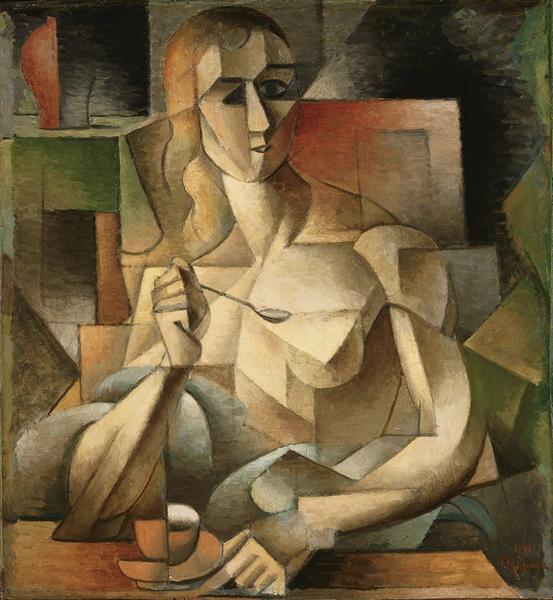

Jean Metzinger, Le goûter (Tea Time), 1911

Jean Metzinger, Le goûter (Tea Time), 1911

1

The Mona Lisa of the 1911 Salon d’Automne

What he hoped to do with painting was to create

an art that…would have nothing to do with the business of creating illusions. I dreamed of painting glasses from which no-one would ever think of drinking…I wanted an art which in the first place would appear as the representation of the impossible (AM, p. 12).

These words are Jean Metzinger’s, published posthumously along with other autobiographical notes presumably written late in life, after the work he became known for in the nineteen-teens was done. They therefore might strike us as an after-the-fact rationalization or apologia. But they are consistent with statements he’d made as early as 1911’s “Cubism and Tradition,” where he described Cubist painters as having

allowed themselves to turn round the object, to give of it, under the control of the intelligence, a concrete representation made up of several different angles [aspects]…In painting, any audacity is allowed if it increases the pictorial power. To draw the eyes of a portrait full face, the nose in a three quarter view and to divide the mouth in such a way as to reveal the profile – that could well, so long as the worker possesses the necessary degree of tact – greatly increase the resemblance and, at the same time, at a crossroads in the history of art, indicate the path that should be followed.

This comes very close to describing Metzinger’s Le Goûter, painted around the same time that “Cubism and Tradition” was written. The painting was displayed at the 1911 Salon d’Automne, where it drew a good deal of attention and was dubbed the Mona Lisa of Cubism by the poet André Salmon (Cox, p. 176).

Le Goûter, known in English as Tea-time, shows a woman sitting at a table in a semi-dark room whose space is solidified into planes and cubes at the margins; she is caught in the act of lifting a spoon to her mouth. Behind her right shoulder a vase stands in a shadowy niche; in front of her on the table is a cup. The colors are subdued and mostly drawn from a typically Cubist range of ochres, blue-grays, roses, buffs, and olive-greens. The woman is painted in a style also recognizably Cubist – she is faceted and the left side of her face is shown full-on while the right is shown in profile – but only moderately so. Her face and figure are fully legible, unlike the more rigorously decomposed figures and portraits Picasso and Braque were painting; as Linda Dalrymple Henderson suggested in her essential study of the fourth dimension in modern art, with Le Goûter Metzinger seemed to have been more interested in portraying figures in a volumetric manner similar to Cézanne’s rather than in following the more extreme Cubist experiments of dismantling them and distributing them across planes implying multiple perspectives (Henderson, p. 85). A notable exception here is the cup.

The cup is shown from two perspectives simultaneously. Its right half consists of a semi-circle, which implies a view from the vertical, while its left half shows it as seen straight on from the front, implying a view from the horizontal. It may seem at first to be a minor feature in the larger context of the painting’s composition, but a closer look tells a different story. This bi-perspectival cup occupies a central position if not on the canvas, then in the relationship between the viewer and the picture – and particularly between the viewer and the woman in the picture –, a relationship it mediates. Its dual perspectives render it legible as something seen frontally, by the viewer standing in front of the pictured scene, and from above, by the woman sitting at the table and positioned above it. It synthesizes both viewpoints and acts as a kind of bridge between the world of the viewer and the world of the woman, which Metzinger has pictured as being organized around her spooning up a taste of tea from the cup. This split-image cup opens up a channel of communication between both worlds.

2

The Cup and the Fourth Dimension

Given its presentation through two perspectives simultaneously, the cup looks like it could be intended as an image of a cup as seen from a higher dimension. Which isn’t surprising, given that talk of the fourth dimension was common among the circle of Puteaux-based Cubist painters, notably among whom were the three Duchamp brothers, that Metzinger frequented at the time Le Goûter was painted. The Puteaux group heard about higher dimensional and non-Euclidean geometries through informal lectures from Maurice Princet, an insurance actuary who’d also introduced Picasso and other Montmartre Cubists to N-dimensional geometry before moving on to the Puteaux circle.

Henderson tells of André Lhote’s recollection of a rhetorical question Princet put before the Puteaux Cubists concerning the distorting effects different perspectives have on the way we view objects, and consequently how artists would have to “straighten up” the way objects were depicted if they were to render them as types free of the accidents of particular points of view:

You represent by means of a trapezoid a table, just as you see it, deformed by perspective, but what would happen if you decided to express the table as a type? You would have to straighten it up onto the picture plane, and from the trapezoid return to a true rectangle…[T]he same straightening up process would have to take place with [the objects on the table]. The oval of a glass would become a perfect circle. But that is not all: this glass…seen from another angle [is] nothing more than…a profile whose base and rim are horizontal, whence the necessity of another displacement…(Quoted in Henderson, p. 68).

This is striking when we consider that Metzinger’s tea cup, with its opening shown as a circle from the vertical and its face as a horizontal profile, conforms to Princet’s analysis as if to a formula.

And yet if the tea cup had been intended to be something depicted from the multiple perspectives of a higher dimension, it still is clearly recognizable as a tea cup. Which is not always the case with visual portrayals of upper dimensional objects. When we attempt to depict an object in four dimensions on a two-dimensional surface such as a canvas, it frequently loses its legibility; it becomes unrecognizable as the object it is. Hence it has been suggested that the teacup picture represents Metzinger’s emphasizing the legibility of the figure over the attempt to depict four-dimensionality (Henderson, p. 85). The teacup in fact seems to have it both ways. It is easily identified as a teacup. At the same time, it does present itself as being seen from different perspectives rather than from a single fixed point.

Assuming that Metzinger’s portrayal of the teacup from a dual perspective was inspired by Princet and talk of the fourth dimension, rather than ask whether it represents the integration of a higher dimensional schematic within a larger return to a more prosaic system of depicting objects, we might ask instead whether it reflects a particular conception of what the fourth dimension is supposed to be.

3

The “Total Image”

As Henderson notes, for the Cubists of the Puteaux group the fourth dimension, as well as non-Euclidean geometry, meant “a higher reality, a transcendental truth” that would be the product of the artist’s grasp of the object through the mind (Henderson, p. 78). This notion is implicit in Princet’s comments about depicting objects as types rather than as appearances based on accidents of perspective. Consequently it was crucial to the Cubist project that the object as depicted on the canvas would originate as much in the mind of the artist as in the visible material thing represented; the cubist object was as much idea as thing. This is borne out in On “Cubism,” an important theoretical and programmatic statement Metzinger wrote with Albert Gleizes in 1912. There, the authors called for “[a]s many images of the object as eyes to contemplate it, as many images of essence as minds to understand it” (Herbert, p. 12). Accordingly, the authors take Cubism’s forerunners to task for

not suspect[ing] that the visible world only becomes the real world by the operation of thought, and that the objects which strike us with the greatest force are not always those whose existence is richest in plastic truths (Herbert, p. 2).

It is important to note here that Gleizes and Metzinger’s “visible world” is a kind of shorthand for the sensually perceived world in general; in particular, it includes the world that reveals itself through our sense of touch. As they explicitly state, “[t]o establish pictorial space, we must have recourse to tactile and motor sensation, indeed to all our faculties” (Herbert, p. 7), Presumably Cubism, with its view beyond the plain version of the world as it gives itself to our senses alone, would not only suspect the reality of this mind-illuminated world, but would find a way to translate that finding into a visual vocabulary.

Metzinger earlier mooted the notion that painting should reveal the object “as minds…understand it” in his “Note on Painting” of 1910. In that statement he claimed that Picasso was striving to depict things through what Metzinger called the “total image,” or a way of portraying the object which would draw on the idea the artist discovers in the object as well as on the object’s appearance. Metzinger claimed that Picasso was engaged in “illuminat[ing] the object with his intelligence and with his sensibility…bring[ing] us a material account of [objects’] real life as it is lived in the mind” thanks to a “free, mobile perspective” whose various viewpoints are synthesized in a mental act of understanding. Whether or not this could be said to have been Picasso’s intent is debatable but in a sense irrelevant; Metzinger saw these qualities suggested in Picasso’s paintings and made a cogent case for their being there in fact if not by design. Looking beyond Picasso, Metzinger’s larger point in the “Note” was that to the extent that painting could capture or convey these qualities, it would depict “the equivalent…of an idea – the total image” of the object, and one that would thus transcend the contingent limitations of a given visual perspective arising from a fixed point in space.

Or indeed, of time. In “Cubism and Tradition,” an essay that appeared in the Paris Journal in August, 1911, Metzinger wrote that the Cubists

have allowed themselves to turn round the object, to give of it, under the control of the intelligence, a concrete representation made up of several different angles [aspects]. Already the picture was in possession of space, and now it reigns also in time [la durée].

The Cubist image, in addition to synthesizing multiple spatially distributed viewpoints, would also synthesize viewpoints that are distributed in time. The resulting image – the total image – would thus present the object as it is grasped moment-to-moment as well as from angle-to-angle. This view-of-all-views is the view from a viewpoint metaphorically above all viewpoints after having been seen through all viewpoints, and beyond time as having been grasped through time. The total image on the Cubist canvas, in other words, would portray the object as having been precipitated out from the accidental, and necessarily incomplete, perspectives particular to perceptions limited to any given place or any given time. At a first pass, this would seem to mean that the total image would count as an image of the Ideal object sub specie aeternitatis – from the perspective of the eternal. And for some Cubist painters and commentators, this may have been what the Cubist image purported to do. This wasn’t necessarily true for Metzinger, however.

4

The Object, The Eidos, and the Poetic

What Metzinger’s total image depicts is, in effect, the object as an eidos – as a presentation grasped by the mind. The object as eidos is the object as an idea, and hence we can see how in the “Note” Metzinger could describe the total image as the plastic equivalent of an idea.

Interestingly, something of the history of the word eidos (εἶδος) is expressed in Metzinger’s notion that the painter could represent an object as a “concrete representation made up of several different angles” “under the control of the intelligence.” As used by Homer and the pre-Socratic philosophers, eidos meant “what one sees,” “appearance,” or the “shape” of a body or physical object. By the time of Herodotus its meaning had been broadened and become abstracted to include “characteristic property” and “type,” which is to say it evolved from a designation for the physical “look” of a thing to a representation of the stable features defining a thing as the thing it is, in its Ideal state (Peters, p. 46). Metzinger’s total image, in presenting the object as the mind grasps it by portraying it as a synthetic unity of appearances, seems to contain not only this later meaning of eidos, but the earlier meaning as well.

There is an important way in which the eidos behind Metzinger’s total image surpasses the later meaning of eidos as an Ideal. For Metzinger, what the artist aims to portray is determined as much by his or her affective relation to the object as it is by the object’s essentially defined features or properties. It is, in other words, the object as subjectively intuited as well as objectively constituted. As he and Gleizes put it in On “Cubism,”

We seek the essential, but we seek it in our personality, and not in a sort of eternity, laboriously fitted out by mathematicians and philosophers…All plastic qualities guarantee a built-in emotion, and…every emotion certifies a concrete existence.” (Herbert 11-12)

This seems to me to be a key declaration, and one that sheds light on what Metzinger in particular sought to bring out in his depictions of objects. In addition, it tells us much about how Metzinger thought of the n-dimensional geometry he invoked in his concept of pictorial space. These higher dimensions were for him not simply geometrical, nor were they associated with the realm of the Ideal object grasped sub specie aeternitatis. They were indicative instead of a transcendental grasp of the object in which, as stated in On “Cubism,” “profound realities merge insensibly with luminous spirituality.” To get a full sense of what they were taken to be we would have to take Gleizes and Metzinger’s invocation of “spirituality” and the artist’s “whole personality,” as well as their assertion that plastic qualities are inherently associated with emotions, as showing us the way in. Metzinger in fact explained this in a conversation with Herschel Chipp in 1952. As Chipp reported it, Metzinger asserted that the Cubists’

ideas in painting necessitated more than the three dimensions, since these show only the visible aspects of a body at a given moment. Cubist painting…needed a dimension greater than the Third to express a synthesis of views and feelings toward the object. This is possible only in a “poetic” dimension in which all the traditional dimensions are suspended. (Chipp, p. 223)

In a related thought expressed in one of his autobiographical notes, Metzinger described Princet as thinking of mathematics as an artist would: it was “as a specialist in aesthetics that he evoked continuities in n dimensions.” The lesson Metzinger seems to have taken away from talk of higher dimensions thus was primarily of a poetic, rather than a more narrowly Platonic, nature.

5

The Cup, the Diagram, and the Agalma

To the extent that Cubism was concerned with depicting objects in their eidetic as well as physical dimensions, John Berger has suggested that

[t]he Metaphorical model of Cubism is the diagram: the diagram being a visible, symbolic representation of invisible processes, forces, structures. A diagram need not eschew certain aspects of appearances: but these too will be treated symbolically as signs, not as imitations or recreations…the diagram…suggests a concern with what is not self-evident…it can reveal the continuous. It differs from the model of the personal account in that it aims at a general truth. (Quoted in Kozloff, p. 6)

When the appearance of the Cubist image is considered, Berger’s suggestion makes sense. The Cubist image often renders the object in a manner that resembles a diagram or exploded-view drawing that breaks a thing down into an arrangement of parts. Metzinger’s cup doesn’t seem to fit this model, though, even if, given what we know of Metzinger’s intentions, it does seem right to describe it as a “representation of invisible processes, forces, structures.” I would suggest that a better metaphorical model would be what Plotinus provided when he described Egyptian temple carvings as representing “images [ἀγάλματα (agalmata)] conveying “a kind of knowledge or wisdom” in non-discursive form (Ennead V.8.6 line 24). The kind of image (ἀγάλμα [agalma]) he had in mind was an expression of a Platonic idea in visual form by virtue of which the illustration of a thing would convey the essence of the thing illustrated. In Erik Iversen’s succinct formula, what Plotinus had in mind was a “true symbolic system…in which abstract notions and ideas could be expressed by means of concrete pictures of natural objects” (Iversen, p. 49). Plotinus is presumed to have been speaking of hieroglyphs, which Cubist images do not resemble. But I would suggest that what he claims for these images is remarkably close to what Metzinger claimed for Cubism’s total image.

(A brief digression here to note another similarity between Plotinus’ agalma and Metzinger’s total image: The abstract ideas Plotinus’ images were purported to convey were, like the images themselves, held to be non-discursive and to be embodied as “images not painted but real,” “images existing in the soul” (Ennead V.8.5). Plotinus’ use of “image” as the metaphor to describe the way these essences were embodied in the soul or mind was meant to dramatize his contention that they were not something taking the form of a set of linguistically expressed propositions or statements. Metzinger’s “synthesis of views and feelings toward the object” and “profound realities merg[ing] insensibly with luminous spirituality,” which necessarily encompass the non- or pre-linguistic domains of perception and affect, would seem no less to require a non-discursive form of embodiment.)

To be sure, the idea that the Plotinian agalma purported to capture consisted of the essence of the object in its intelligible form. If we include the affective or imaginative dimensions –Metzinger’s “poetic” dimensions – coloring our encounters with objects as among the factors through which they are made more fully intelligible to us, then the Cubist total image might be described as something like Plotinus’ agalma, perhaps in a form expansive enough to embrace the depiction of affective as well as narrowly conceptual content. This would seem to be one way to describe Metzinger’s cup: as an agalma in this special sense. Putting things together, we can say that the total image that is Metzinger’s cup is an agalma depicting an eidetic object whose content is affective/poetic as well as conceptual. It is an agalma, further, that deals in a realism that transcends the illusionistic realism of a more mimetically realistic representation and hence captures the deeper human reality of the object it depicts.

6

Existential Realism

The realism we can find in the total image of Metzinger’s cup is an existential realism. Existential realism is the realism of things as we encounter them. Through our praxes and attitudes we are always already engaged with the things in our world; they make up the furniture of the spaces we inhabit and move through. With our gaze and our touch we project ourselves outward toward them at the same time that they, as the pre-given, are present to us through our knowing them before our knowing knows itself to be knowing. We have a pretheoretical engagement with them and how they are for us before we reflect on them and their meaning, and before we articulate what we take to be their essential properties. Their existence, and our existence among them, precedes their essence.

Our knowing the things of our world is grounded in something prior to knowing as such – it is an engagement rooted in affective involvement. Things mean something to us before they are objects of knowledge because we are involved with them in an intimate way prior to our stepping back from them and taking up a position vis-a-vis them as objects opposed to ourselves as subjects. We are surrounded by them, we see them and touch them as we integrate them into our mundane activities, use them and ignore them. They belong to our existence before they belong to the categories by which we properly distinguish them and know them; they contain possibilities for us before they display abstract properties.

How does this relate to Metzinger’s total image generally, and to the cup in Le Goûter specifically? To grasp the reality of the object in terms not only of its appearance and status as a general type, but in terms as well of its affective, or what Metzinger calls its “spiritual,” relationship to us – its poetic value – is to grasp it as something that isn’t just a thing existing “out there” in the world, but a thing that is something of significance to us in our world. To portray an object from several perspectives at once, to give a sense of its tactile profile in the round and of its duration in time, isn’t to distort it or alienate it from our senses, nor is it to show it as an intelligible Form transcending the physical shape in which it is embodied. It is instead to bring out the unthought-about intimacy we have with it as a thing we encounter with our eyes and hands as a matter of course. As Merleau-Ponty put it,

What I call experience of the thing or of reality – not merely of a reality-for-sight or for-touch – is my full co-existence with the phenomena (M-P, p. 318).

Merleau-Ponty’s “full co-existence with the phenomena” expresses in more rigorously philosophical terms Metzinger’s “synthesis of views and feelings toward the object.”

7

The Cup in the World

Consider again how Metzinger’s cup is seen from two perspectives – as it would be from a body in motion. The eye, as it takes the cup in from different angles, doesn’t contemplate it, but rather moves around the cup in the course of the cup’s being engaged in the life of the person into whose visual and tactile fields the cup projects. That person is the woman in the picture. The cup is there, an object in use, integrated into her daily life as she lives it. Its significance to her is signaled by its presence there; she isn’t thinking about it, she doesn’t encounter it as an aggregate of physical features or as the accidental and imperfect embodiment of Ideal qualities. Rather, she spoons up a taste of the tea it contains. It is a medium through which she projects herself into a world as much constituted by her needs and concerns as by the shared habits and utensils – like the cup – that transcend her and that she in turns transcends through the uses she makes of them.

That is where the realism of Metzinger’s total image comes into play. The cup as he depicts it is above all a part of a world. It takes its place among the patter of habits, beliefs, desires, projects, imaginings, and so forth that taken together are the world of the woman whose cup it is. The cup in all of its dimensions – visual, tactile, ideal, imagined – is part of a world and all of its dimensions. Paradoxically, then, given his statement in his autobiographical note, Metzinger is giving us his cup as something we very well could imagine ourselves drinking out of.

◊ ◊ ◊

References:

Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art: A Sourcebook by Artists and Critics (Berkeley: U of California Press, 1968). Internal cite to Chipp.

Neil Cox, Cubism (London: Phaidon Press, 2000). Internal cite to Cox.

Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, “Cubism” [On “Cubism”], in Robert L. Herbert, ed., Modern Artists on Art, Second, Enlarged Edition (Mineola, New York: Dover, 2000). Internal cites to Herbert.

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (Princeton: Princeton U Press, 1983). Internal cites to Henderson.

Erik Iversen, The Myth of Egypt and Its Hieroglyphs in European Tradition (Princeton: Princeton U Press, 1993). Internal cite to Iversen.

Max Kozloff, Cubism/Futurism (New York: Harper & Row Icon Editions, 1974). Internal cite to Kozloff.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, tr. Colin Smith (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1967). Internal cite to M-P.

Jean Metzinger, “Afterword to On ‘Cubism,” tr. Peter Brooke, www.peterbrooke.org/form-and-history/cubisme/1947-metzinger.html

Jean Metzinger, “Cubism and Tradition,” tr. Peter Brooke, www.peterbrooke.org/form-and-history/cubisme/tradition.html

Jean Metzinger, “Note on Painting,” tr. Peter Brooke, www.peterbrooke.org/form-and-history/cubisme/note.html

F. E. Peters, Greek Philosophical Terms: A Historical Lexicon (New York: NYU Press, 1967). Internal cite to Peters.

Plotinus, Ennead V, tr. A.H. Armstrong, Loeb Classical Library LCL 444 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard U Press, 1984).

◊

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).