A Review: Beat Not Beat

Daniel Barbiero

December 2022

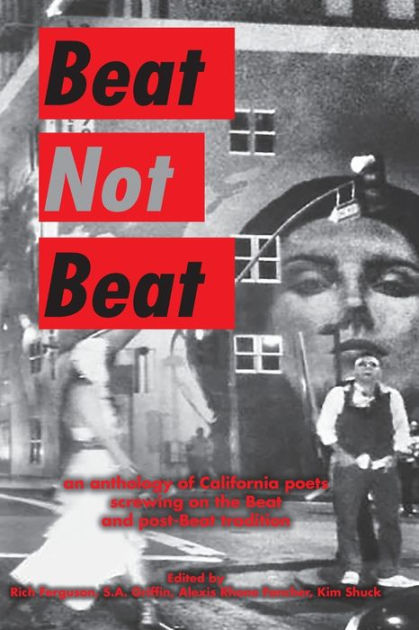

Beat Not Beat

An Anthology of California Poets Screwing on the Beat and Post-Beat Tradition

What is Beat? What is not Beat? The questions sound rhetorical, and in truth, it may turn out that they are. Or perhaps not. Either way, they are raised by the title of this comprehensive anthology edited by Rich Ferguson, California’s Beat Poet Laureate from 2020-2022, with over 170 California poets past and present, some of whom are recognizably Beat, some of whom were precursors of Beat, some of whom rejected the label “Beat,” and some of whom—the contemporaries among them—are inheritors of, or somehow in dialogue with the tradition of, Beat poetics.

“Beat” seems easy enough to identify when we see it, but difficult to define when we try. We know what it’s generally taken to be: a phenomenon encompassing a trinity of elements, to wit, beatitude, or the kind of vision that sees the sacred, however understood, in the profane and the transcendental in the immanent; an attunement to the rhythmic beat that runs through music, structures the spoken word, and ultimately pulses through living beings; and the beaten-downness of the outsider and dispossessed, of those Kerouac called the “fellaheen” existing on the fringes of a culture. Does that mean that everything else is Not Beat? Or is it instead Beat that hasn’t yet realized itself as Beat? If the Beat of beatitude can see the spiritual in the material and even in the materialist’s denial of the spiritual—can see beatitude permeating everything no matter how apparently fallen– then can it also see the Beat latent in the Not Beat?

It may be that, like a Zen koan, the question of what is Beat has no ready answer, and certainly not the kind of hard-bordered answer we would recognize as such. In conversation on the literary podcast Otherppl with Brad Listi, co-editor S. A. Griffin has said that Beat is “whatever you want it to be—now go!” Which it is, or can be. But it does seem that Beatness is a something of a certain weight and reach, and that it does inform a poetics that itself is an expression of that underlying something onto language. What that something is, I would suggest, is a mode of existence, an existential orientation or way of being in the world that grasps the world in its immediacy, responds to it with a generosity borne of spontaneity, and sees in its contingency a meaning that transcends the accidents and imperfections present to perception alone. Like Blake, a spiritual ancestor of Beat, the Beat can see that you “hold infinity in the palm of your hand/And eternity in an hour;” like the Surrealist—another, if less acknowledged ancestor of Beat—the Beat can find the marvelous in the mundane. The Beat vision is above all visionary.

Beat as an existential ideal is a particularly intuitive way of projecting oneself into the world, before the second-guessing and self-alienation of reflection and deliberation have a chance to intervene and break the connection. But it doesn’t end there. At some level the Beat vision reaches toward that point at which the ostensible contradiction between the directly participative immediacy of intuition and the analytical distance of reflection disappears or reveals itself to be one moment among a series of moments moving toward a more encompassing whole. And that next moment—the moment at which that apparent contradiction appears to disappear—may be a moment of self-consciousness, when the Beat artist as universal-concrete comes up against the brittle walls of his or her “I” and somehow pushes through them, with a Kierkegaardian leap into—into what? It would seem that that’s for the artist to say. At that point explication hits rock and its spade is turned. Thus to be Beat is to be the universal-concrete individual, but in a way that ultimately—inevitably—proves to be paradoxical.

Beat poetry is just as hard to define. Although there is no one way for Beat poetry to be, there are certain characteristics that mark a poem as Beat or situate it as being within the Beat tradition—there is, as Ferguson told Listi, a certain “essence of Beat” that marks a poem as having Beat as its point of reference, even if the poet doesn’t consider him- or herself to be a Beat poet as such. This essence would include an attentiveness to language as having a musical element, particularly as exhibited in the spontaneity of spoken language. Beat poetry plays out in improvisational cadences, surging forward and falling behind as the thought it rides flows and ebbs, its line driven by the momentum of its own coming-into-being the way an improvised solo propels itself according to an unfolding rhythmic or harmonic logic. Beat musicality is at the service of an expressiveness rooted in a desire to engage with and convey something of the immediacy of experience. Thus its inclination to draw on a diction with its origins in the vernacular actually used between people—what Lew Welch once called “the general din of the speaking world.”

At the same time, it’s important to note that the Beat ideal of spontaneity in language needs some qualification. The well-known formula “first thought best thought” doesn’t capture Beat writing in its entirety; more often than not the first thought is a point of departure rather than a final destination. It’s well-known, for example, that both Ginsberg’s poems and Kerouac’s prose were meticulously crafted into the forms they finally took. (By the same token, the apparent spontaneity of jazz improvisation is itself the product of hours of practice and preparation; what we think we hear as completely in-the-moment playing is in fact crafted from a thick base of underlying skill and executed with discretionary judgment. To that extent, jazz is a more fitting model of Beat poetics than many might at first realize.)

In the end, Beat poetry’s essentially democratic language reflects its willingness to include within it all aspects of experience, including the “unpoetic.” It is a willingness to contain multitudes, as Beat forebear Walt Whitman, the great democratizer of poetic language, expressed it. And underneath it all is an implicit sense of sincerity.

All of which may just be a more elaborate way of saying, with Griffin, that “you’ll know it when you see it.”

Beat Not Beat contains several generations of poets and juxtaposes them in a way that is structured neither by chronology, stylistic or social affinity, nor locality. All of them are Californian or significantly associated with California (which explains why, for instance, no poems by the predominantly East Coast Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac are included).

Of Beat forerunners, Beat Not Beat includes two of the most important: Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Patchen. (A third, Robinson Jeffers, unfortunately couldn’t be included due to copyright complications.) Rexroth in particular was a central figure around whom many San Francisco poets affiliated with various competing and cooperating circles—Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, William Everson, Philip Lamantia and others—coalesced at one time or another. Patchen, Rexroth’s contemporary, exerted a forceful influence on West Coast writing as well. Both Kenneths helped introduce jazz into poetry readings—a signature feature of Beat poetry, at least in the popular imagination—and both eventually took a skeptical attitude toward Beat, not least because of the media circus that gathered around the movement. Both are represented by brief poems, Rexroth by the bitterly ironic “Fox,” and Patchen by the imagistic “But of Life.”

Moving past forebears, Beat Not Beat includes a good number of poets readily identified as Beat: Gary Snyder, whose orientation toward nature was influenced as much by Rexroth as by classical Chinese and Japanese poetry; Neal Cassady, who stands at the center of any account of the Beats; Carolyn Cassady; Diane di Prima; Bob Kaufman, Lawrence Ferlinghetti; Joanne Kyger; David Meltzer; and Stuart Z. Perkoff.

Snyder’s “Night Song of the Los Angeles Basin” finds mythic resonance in the local flora and fauna, even as the human environment of freeways, traffic, and artificial light encroaches. As its title indicates, Cassady’s 1951 “Third Anniversary Poem” to wife Carolyn is a light, occasional piece; it wasn’t for writings like this that Cassady exerted a major influence on the Beats but rather for the recently rediscovered Joan Anderson Letter, which helped open a way to the more spontaneous writing that would become a hallmark of Beat. Carolyn Cassady’s “Poetic Portraits” is a cutting anecdotal sketch of Allen Ginsberg drawn from recollected conversation. Di Prima’s “He Breathes” is a touching chain of thoughts both profound and trivial connected by news of the death of Gregory Corso. The powerful images and metaphors of Bob Kaufman’s “Would You Wear My Eyes” captures the beat-down aspect of Beat, its title/closing line seems a challenge to the reader: would you want to see the world or yourself from this perspective? From the pacifist side of Beat comes Ferlinghetti’s sarcastic “Salute!”, an anti-violence, anti-authoritarian mockery of the homicidal state and its various apparatuses—armies, internal security forces, foreign services—written in 1968 from Santa Rita Prison, where he was incarcerated following his arrest at an anti-war demonstration. Kyger’s “Destruction” is a shaggily humorous narrative of a bear breaking into a cabin, wreaking havoc and eating everything in sight—including a stash of psychedelics. With “Re: 2016,” written on the eve of the New Year, Meltzer captures the spirit of beatitude in showing what life’s contingency looks like when seen through the lens of gratitude and openness. The untitled poem by Perkoff, a central figure on the Venice West Beat scene, is a cautionary tale of the muse coming to reclaim her gift.

Of special note is the inclusion of Philip Lamantia. Lamantia, a San Francisco native and son of Sicilian immigrants, had a long and varied career as a poet, and was associated with the Beats for a time. His importance to the movement was in the living connection he provided to Surrealism. As a teen poet he declared himself for Surrealism, was hailed by André Breton as an American Rimbaud, and briefly moved to New York to work on the Surrealist-aligned magazine View. Ferlinghetti credited him with being the “primary transmitter of French Surrealism” to America and consequently with having a formative influence on Beat writing. In fact Beat’s bias toward taking spontaneous, stream-of-consciousness writing as a starting point was significantly underwritten by Surrealist automatic writing. Appropriately enough, Lamantia is represented by “Poem for André Breton,” a recollection of the last time he saw the Surrealist leader, in New York in 1944.

The heart of Beat Not Beat is its collection of contemporary poets. Their poems occupy different points along the continuum that is the Beat tradition, as it continues to evolve and survive in shape-shifting form. Their work reveals different facets of the Beat sensibility and poetics while at the same time maintaining a core of recognizably Beat qualities, adjusted for changing times and circumstances, not all of which may necessarily be found in any single poem or even in an individual poet’s body of work.

The beatific side of Beat flourishes in Kimi Sugioka’s aptly named “Temporal Beatitudes.” To find the beatitude in existence is first to recognize its complexities and paradoxes; Sugioka reminds us that to be human is to be “a traitor and a saint living in the same shell” for whom “the whole is a fragmented universe/we carry like a dim in our pockets.” In “A New World in Our Hearts,” Richard Modiano locates the serendipity of everyday satori in the eternal now of that “one moment that seems to eclipse the past and future.” Ron Koertge’s “Annunciation at Pico and Sixth” describes a literal vision of beatitude in an unlikely place, as it tells of a cop seeing a resemblance to a painted image of the Virgin Mary in the form of a suspected DUI he’s just pulled over. And Eric Morago, in the poignant “Smolder,” draws a correspondence between roadside fire seen during his commute and the ardor that drove his younger self to poetry and outrage, before the responsibilities of job and mortgage came along. And yet that fire still leaves its trace “of smolder and ash” in the fact of his continuing to write. Which shows that the Beat vision can survive even in the most apparently hostile of environments.

“San Francisco Ocean Beach Blues” by devorah major updates the Beats’ visionary nature poetry to take on contemporary ecological concerns regarding the despoliation of the littoral habitat, as she contrasts memories of an unruined beach with the present reality of the ocean’s “foam skirts full of trashed dying fish and marooned whales.” In a related mode, Linda J. Albertano questions the value of advanced technologies for a humankind with too much intelligence and too little wisdom in the ironically titled “Progress.” A different kind of skepticism animates Paul Corman-Roberts’ “The Explanation of Everything,” a meditation on the pretensions of thought to give an unequivocal, overarching explanation of the “the impossibly/dense/contradiction of existence.” If discursive reason falls short of reducing the perverse polymorphousness of experience to its own terms, Kathryn de Lancellotti’s “Root” suggests that a divinatory outlook, in which the natural world’s events are read as signs, is one viable route to grasping the intelligibility of the life in front of us. Another alternative is silence, for which Peggy Dobreer’s “A KARA: U KARA: M KARA: TI” provides a beautifully articulated, extended metaphor.

The Beat tradition of social criticism—the adversarial perspective of the beaten-down—is brought into the present with a number of poems. Tongo Eisen-Martin, the current Poet Laureate of San Francisco, offers “A Sketch about Genocide,” a passionately voiced protest of contemporary racial dynamics, while Matt Sedillo’s “City on the Second Floor” articulates a strike at the economic inequities of globalization. A. K. Toney’s “Sankofa Scars” draws on the collective memory of the African diaspora to make the point that “the power of the past is a lasting knowledge.” Rich Ferguson’s “When Called in for Questioning” takes place against the pathos of an existence that often evades our sense of what’s right, but is a reminder that we nevertheless can reach a serene wisdom where “the heart is equidistant from joy and suffering.” Past U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass contributes “Dancing,” a long-lined poem tracing the technologies and pathologies of gun violence from its beginnings in the discovery of fire to its culmination in mass killings in contemporary America.

The Surrealist influence on Beat poetics is well-represented by Natasha Dennerstein’s “Palm,” a dense prose poem whose forward momentum of images seem to have sprung automatically from the hidden wellsprings of the mind. The late Q. R. Hand, Jr.’s “Defense Offense Back Fence” features a similar perpetual forward motion, but this time the propellant is the rhythm and melody of the vernacular—the beat in Beat—which carries his long lines on the music of internal rhymes and near-rhymes of both vowels and consonants. In contrast to Hand’s profoundly embodied language, Will Alexander’s highly abstract “Anterior Speculation” pushes right up to the borders of Beat as it enunciates a cryptic puzzle regarding the poetic potential of “higher states” which, he hints, may carry within them their own limitations.

No brief review can do full justice to a selection of poetry as rich and diverse as that found in Beat Not Beat. But perhaps the above sampling of its poets will convey something of its flavor and will, I hope, encourage readers to explore the volume for themselves.

Beat Not Beat: An Anthology of California Poets Screwing on the Beat and Post-Beat Tradition

Edited by California Beat Poet Laureate Rich Ferguson

Co-editors: S.A. Griffin, LA poet Alexis Rhone Fancher

and former S.F. Poet Laureate Kim Shuck

Published by Moon Tide Press, 2022

Moon Tide Press →

Beat Not Beat website→

◊

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer and writer in the Washington DC area. He writes on the art, music and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021).