The Oracle’s Regret

Daniel Barbiero

April 2020

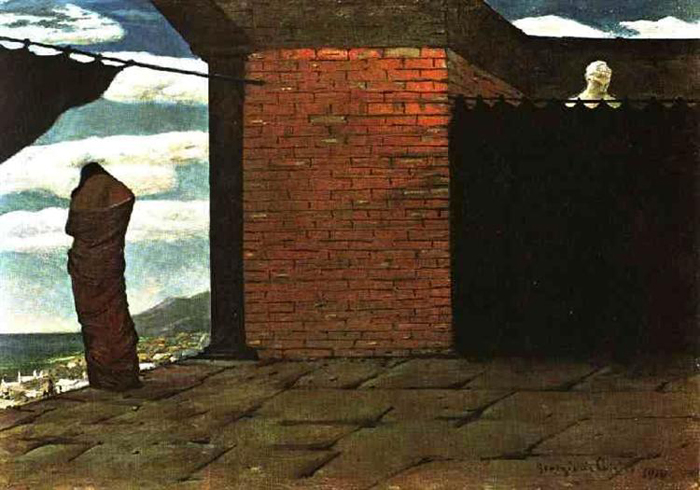

The enigma of the Oracle, 1910, Giorgio de Chirico

The enigma of the Oracle, 1910, Giorgio de Chirico

“The Engima of the Oracle”

A figure, slightly bent and seemingly absorbed in thought, stands at the threshold of an apparently roofless temple on a hill overlooking a city. Inside the temple and at the figure’s back, behind a drawn black curtain, is a statue whose head and shoulders are just visible above the top of the curtain. This is the central imagery of Giorgio de Chirico’s early metaphysical painting “The Enigma of the Oracle.” As with many of de Chirico’s paintings from this period, the mise-en-scene of “The Enigma of the Oracle” crystallizes a mood whose precise meaning becomes less clear the more we try to engage it directly. The picture is all implication and riddle; like the stereotypical oracular utterance, it has something to say—if only its layers of mystification can be peeled back.

The pensive figure we know was based on the central figure in painter Arnold Böcklin’s depiction of Ulysses on the island with Calypso. But in de Chirico’s painting the figure’s identity isn’t so clearly set out. Based on the painting’s title, it’s fairly certain that he—or she; de Chirico’s depiction is ambiguous on this count—is situated in a sanctuary for an oracle. The figure’s posture signals withdrawal and introspection: leaning, or rather slouching, forward, head down, a pose stereotypically signaling absorption in thought—thought that either preoccupies him or her abstractly, or else is disturbing. Is this a querant whose consultation of the oracle has led to unsettling news? Possibly, but the title seems to point to the oracle as the subject of the painting, and as the focus of the enigma. The likelihood is that the pensive figure is supposed to be the oracle herself. (As the most important oracles in the Hellenic world were women, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to read the painting’s protagonist as, if not female by the artist’s design, then at least as female by virtue of its representing an office that in its more significant instances was filled by a woman.) Are we looking at a scene of philosophical meditation? Perhaps; as we know from his early writings, de Chirico was fascinated by the idea of the philosopher caught up in abstract reflection. But in this as in many of the metaphysical paintings there is a pervasive air of melancholy which here is embodied in the figure of the oracle. If we read the painting as showing a dejected oracle, we might ask where this melancholy comes from. What enigma gives rise to it? And what specific form could it take? But what could an oracle regret?

Oracles as Language Games (Obscurity and Meaning)

Perhaps the most famous oracles—the oracles that come closest to embodying the qualities we most often associate with oracles, precisely to the extent that they are so well-known—are the oracles in hexameter verse such as those Herodotus recorded in his Histories. But as Plutarch shows in his dialogue “The Oracles at Delphi No Longer Given in Verse,” oracles often were given in prose. Further, not all oracles were obscure; some were clearly worded, yes-or-no answers to simple, mundane questions about personal or household matters.

But however plainly worded many oracles may have been, oracles as a type of utterance were famous—notorious—for their obscurity. The interpretation of many famous Delphic oracles—the response to Croesus’ question of whether he should attack Persia; the statement that Athens’ wooden walls would protect the city from the Persian invasion—was often a matter of speculation. As in the case of Croesus’ interpretation of which empire would fall should he attack Persia, such speculation could go spectacularly wrong. As Heraclitus was reported to have said, the god speaking through the oracle neither revealed nor concealed, but rather gave a sign. The oracle gives a sign in the broadest sense of the meaning of sign, that is, as something whose meaning has to be inferred: a sign that has to be interpreted through the figures of speech, images, and circumlocution in which it was transmitted. Oracular utterances could thus be likened to moves within a particular type of language game that follows certain rules that are in turn governed by certain assumptions regarding meaning and voice.

The first assumption is that, despite the riddling nature of the utterance, the oracle does in fact mean something specific by it. This has to be assumed from the outset. Simple enough. But then why make that meaning difficult to ascertain? The obvious answer is that the oracle’s obscurity represents a natural rhetorical strategy for safeguarding the credibility of prediction. The obscurity of the oracular utterance is a hedge against failure—a muddying of the querant’s capacity to determine the meaning of the utterance, or more specifically, to have a clear picture of the conditions that would have to hold in order for the utterance to count as true. The obscure utterance prevents the clear ascertainment of what state of affairs would have to obtain for the utterance to be true—for it to have accurately predicted what in fact came about, for example, or to have correctly described a situation in which the querant must then take the appropriate action.

Such an answer, however correct it may have been in actuality, would have to be ruled out inasmuch as it falls outside of the language game of oracular consultation as understood and practiced. The oracle can’t simply be assumed to speak in a way that would allow her to dodge responsibility; something like a sincerity condition would have to be understood to bind her to her utterance. Rather than being assumed to be an evasive speaker she could instead be taken to be a mouthpiece of possibly limited means who, as an intermediary between the god and the querant, chose the actual wording of the utterance. Theon, speaking in Plutarch’s dialogue, may have described what many felt when he asserted that the god himself wasn’t responsible for the wording of the Delphic oracle’s utterances but instead simply “supplie[d] the origin of the incitement” to utter them. The god was the source of the utterance’s inspiration, not of the particular form the inspired utterance took; he made known his thoughts but did so through the medium of a particular person, who would put them into language as best as she could, given her own verbal and other limitations. On this account the oracle is best thought of as an interpreter rather than a transparent conduit, and as such as the unwitting perpetrator of an act of—potential, if not actual—distortion interposed between receipt of the god’s intended message and the transmission of that message to the querant. If the oracle’s prediction seems not to come about it isn’t because the events the oracle predicted did not in fact transpire, but rather either because the prediction was, in its riddling obscurity, misinterpreted by the querant, or because the oracle’s ability to craft the god’s intention into language was ineffective or inept. The failure is one of translation rather than of vision, or of interpretation rather than of declaration. Meaning as such is still present even if badly phrased or clumsily mismade.

Originary Meaning and Intention

It is the god’s intention that is critical to the meaning of the oracular utterance. That it does play this central role constitutes one of the foundational rules of the language game. The god must be assumed to know the significance of the message the oracle’s utterance is to convey. Without that assumption, the meaning of the oracular utterance, which in a sense is underdetermined by the oracle’s poor or imprecise choice of words and figures of speech, is undermined. There must be a kernel of clarity wrapped in the obscure tissue of the oracle’s diction. And it follows that because the actual choice of words with which the message is transmitted is not the god’s but instead is the oracle’s, the originary meaning of the utterance is, in principle, separable from the concrete locution in which it is conveyed. In the final calculation the question of whose figures of speech, whose images, whose grammar—whose will to obscurity, if that’s what it is–gives the oracular utterance its specific form, is a subsidiary matter of some, but not central, interest to the task of interpretation. In a sense, this question of the oracle’s idiomatic way of putting the message into words is little more than a diversion. What really counts instead is the communicative intention that gives those words their reason for being in the first place.

Does this mean that interpretation of the oracular utterance assumes something like the naïve belief that the utterance is a vehicle for transmitting an intention prior to and separate from the utterance itself? On Plutarch’s evidence, the answer would have to be a qualified “yes.” On the one hand the assumption that the god supplies a prior intention to mean something that must then be articulated through the oracle as his instrument is based on a naïve view of language and how it means. At the same time though, as Plutarch’s Theon acknowledges, the interpretation of oracles presupposes an at least basic understanding of the distorting effects of language on intended meaning. Even if we grant that the communicative intention is fully present to the god, it does not follow that it consequently is fully and transparently present in the utterance. The latter instead acts as a more or less arbitrarily applied filter or prism through which the intention must be ascertained. In any event, though, in engaging in the interpretation of the god’s vision of one’s future one isn’t engaging in analysis drawing on a sophisticated philosophy of language or literary interpretation, one is simply trying to see into one’s own future through the god’s eyes.

Given the assumption that the god means to communicate, and given an understanding of the idiomatic limitations compromising the prospect of obtaining effective speech from any particular oracle, the meaning of the utterance can, with the proper interpretation, be recognized and, presumably, correctly acted upon. All depends on that qualifier—“the proper interpretation.” But what, within the rules of this language game, is it that grounds “the proper interpretation?”

A Metaphysics of Presence

As with any kind of interpretation, one needs to know what one is interpreting for, and in this case the object of interpretation is the god’s intended meaning. That intention provides a guarantee of the legitimacy of the oracular utterance as well as of its meaning—to the extent that either of these factors can be disentangled in this instance. But underlying this guarantee is a more fundamental requirement: the oracular utterance requires the presence of the god who speaks through the oracle. This presence may in fact be illusory for any number of reasons—the nonexistence of the god, to choose one immediately obvious example—but the good faith assumption that the god is present is a basic premise for accepting that the oracular utterance’s carries any sense. Its sense is sense only to the extent that it is what the god intends to communicate.

In fact the oracular utterance would appear to be the case par excellence of a certain type of metaphysics of presence. That it is actually the god who is present, who is taking part in the immediacy of the dialogical situation, and who therefore by that presence both constitutes and legitimizes the oracle’s message, provides the metaphysical underpinning of the entire oracular enterprise. Whether or not this assumption derives from a faulty presupposition about language’s relationship to a prior communicative intention is, in this context irrelevant; the assumption that the god is present to the oracle is the fundamental prerequisite for the oracular utterance to function as it is supposed to function—as a prediction and projection—and thus constitutes one of the ground rules guiding that particular use of language. Whether or not the communicative intention is effectively conveyed through the oracle’s utterance is just as irrelevant on this point. Ultimately, the question is whether or not it is the god who is speaking through the oracle, and this is a question of ontology rather than of the relationship of language to intention. Put another way, the fundamental question is not whether or not the oracle’s message directly reflects the reality it purports to be about, or whether or not a communicative intention is fully present to the oracle; rather, the question concerns what order of being it is who is communicating through the oracle. This is presence in the originary, ontological sense of a living presence of being; it is a matter of who is present, not what is present to the mind of the speaker.

And it is the presence of the god who is supposed to be communicating through the oracle that is the “fact” affirmed by the very taking place of the oracular utterance. The god’s presence is in this sense the very reason for the utterance’s being. (That the “fact” of the god’s presence constitutes the fundamental rule of oracular discourse is simply part of the language game of oracular consultation and interpretation; it doesn’t matter whether or not the entity underlying that “fact”—the god—is in fact real and present. One simply accepts that it is in order to play this particular language game.) The utterance is only meaningful to the extent that the presence of the god is understood to be the locus from which the oracle’s speech issues, and is the source of the communicative intent the oracle’s utterance is supposed to embody.

In sum, in order to accept the conventions of oracular consultation and interpretation, one needs to accept that the god is present in the oracular utterance; that the oracular utterance further embodies the god’s intended meaning; and that that intended meaning conveys accurate information about the future as it interests the querant.

Time and the Oracle

By translating the god’s intention into her own words, the oracle purports to put the future into language. To make a prediction. Is it a really a prediction, though? A prediction would appear to have as one of its conditions the possibility that it fail—that what it predicts does not come about, or at least does not come about in the way that it predicts. (Surely this is the philosophical point Yogi Berra made when he is supposed to have said that predictions are hard to make, especially about the future.) There is an irreducibly speculative edge to the prediction that the oracle’s utterance lacks. She claims to have a privileged view into the future, one granted by the god. By virtue of that borrowed vision, the oracle’s pronouncing on the future takes on the weight of a pronouncement of fact, albeit a fact that has yet to be, and that—by virtue of the oracle’s having seen it or been made aware of it by the god– by the same token has to be. This is unlike a prediction and rather more like a plain statement of fact. As a statement of fact it is strange, though, in that it is a statement of a fact that is not a fact. For, it purports to describe a fact that is as yet non-existent; as a statement, it corresponds to nothing that is. What would make it true is not in existence at the time of utterance; as a statement of fact it corresponds to nothing that is. And yet at the same time, it purports to tell of this something that is not as if it were something that is. The oracle’s pronouncement is, if not literally then at least figuratively always expressed in the future perfect tense—it is about something that will have happened, even if it has not yet happened.

If the oracle’s prediction reveals the future as something accomplished, as consisting in acts or events that have been completed, it is a future very different in appearance from the future as it appears to ordinary humans. For us the future is a projection of the imagination, a hypothetical possible state that in its possibility is not guaranteed to come about but can always not be. This is because possibility is such that its fundamental element is the possibility of failure. Our freedom consists in the possibility that the future we reach will not be the future we anticipate and hope to bring about. Human freedom, to a significant extent, ironically turns on failure: we are free to project ourselves into a future that is open, but that projected future is open only to the extent that we can fail to bring it about or otherwise to reach what we project it to be

To be sure, this freedom is to a significant degree the product of imperfect or incomplete knowledge on our part. Our projection of a future is an imaginative act based on what we can know at the time we project it, which isn’t enough for us to determine with absolute accuracy how the myriad of interacting factors comprising the conditions of any given moment will resolve themselves at some point ahead of us in time. To one who cannot see or grasp these conditions in their entirety and with their full implications the future, as an as-yet nonexistent state following on the existential engagements of one’s present state is, for all practical purposes, indeterminate. (This is so even if the future is in fact wholly determined. Its determination simply exceeds our capacity to grasp it.)

But if one is to believe the oracle, the future is a far different thing: no longer a possibility but instead a necessity. The seer’s seeing is purportedly of an actual state of things, not a hypothetical construct in which the concerns and desires of the present are carried forward and posited as completed in some way. For the oracle the future is a kind of prison without the possibility of escape that failure offers. What the oracle purports to see—the vision vouchsafed to the oracle by the god—is not what may be, but what will be. What in fact must be. To be aware of, rather than hypothetically projecting, a future condition is in a sense to be sentenced to a future one cannot choose and is not free to attempt to bring about. This is the meta-meaning of the oracle’s prediction which, whatever its specific content, is always the same: that time is always already present to the present moment, that what we experience as an ultimately finite series of moments vanishing into the past and projecting inevitably into the future is instead, like Plotinus’ Nous, a static present in which past and future coexist in one unchanging and unchangeable eternity. If the oracle is to be taken seriously as a seer, her experience of temporality is not the human one of the forward-projecting finite series but of a static eternity. To experience oracular time is thus to experience all time all the time. And this is the ultimate refutation of what it is to be human, since to be human is to inhabit time as a constant projection into a future of possibilities. Our temporality, which is to say the way we exist in time, is a temporality of constant becoming—of projecting forward into a future in which we are not yet–and then coming to an end. It is a variety of non-being in which our present is in a sense non-existent and is instead a kind of nothingness suspended between a past that is no longer and a future that is not. It is the antithesis of the radical present that the oracle inhabits.

The Oracle’s Regret

Looking again at the figure in de Chirico’s painting, we can now unravel the enigma attributed to the oracle and source of her melancholy. As an intermediary between the god and the human community, the oracle comes to inhabit a mode of being that sits uncomfortably between the divine and the human. Her experience of time through the god robs her of the freedom of possibility that comes with the ordinary human way of living toward an uncertain future, but it does so without giving her actual divine status as compensation. Her experience of time isn’t really hers; it’s a borrowed, second-hand thing. But it is enough to estrange her from the ordinary human experience of temporality and thereby to displace her from the uncertain ground of what it is to be human.

Without being grounded in the nothingness of the constant becoming that is the experience of human being, the image of eternity, as seen by the oracle, negates what it is to be human. She has no future, just as she has no past. What she has instead is an ever-present present in which past and future are co-present and fixed in their co-presence. Without a future she has no vanishing point to recede into and no horizon over which there is nothing more. Without that sense of time as a coming into and going out of existence—without that sense of time as essentially built on the non-being of the present—she is trapped in a limbo of eternity. Eternity to this extent is its own form of nihilism, a nihilism grounded in the refusal of transience, a rejection of the being-in-flux that colors human life, giving it its freedom and ultimately its meaning. The loss of that experience of transience and its function as the basis of human meaning is the source of the oracle’s melancholy. The eternal just is meaningless. And to have seen this is to regret it.

[The idea for this essay was inspired by soprano saxophonist Gianni Mimmo and violinist Alison Blunt’s “Oracle’s Regret.”]

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.