The Letters of What Is

Daniel Barbiero

September 2020

Evolution 1961, Beverly Willis, 3 -1 ft. squares, oil on masonite

Evolution 1961, Beverly Willis, 3 -1 ft. squares, oil on masonite

“Geometry and its various decorative forms…underlie all matter. The idea from early thinkers that the universe is composed of certain geometric forms is confirmed by present day physics and biology.” — Beverly Willis, Arteidolia, June 2020

The basic stuff of our world may—or may not, we really don’t know for certain and can only conjecture—consist in one dimensional strings vibrating in ten or more dimensions of spacetime. Strings are the latest solution to the problem of finding the originary principle or fundamental ground of being, which was first suggested to be water by Thales of Miletus 2500 years ago. Water is an observable element, but many of the hypothesized originary elements were not; the early Greek atomists, for example Leucippus and Democritus, foreshadowed modern physical theory by postulating an unobservable, undecomposable element or atom (ἀτόμος) as the fundamental stuff of matter. Following these early thinkers, Plato hypothesized that the elemental building blocks of matter were unobservable entities that could be combined and configured to make up the familiar elements of air, fire and water. These unobservable entities were geometric figures: triangles.

***

The early abstractionists are separated from Plato by twenty-four centuries, but they shared his intuition that the foundations of matter are to be found in geometric form. The polygons, lines and circles they put on paper or canvas reduced the three-dimensional world to its two-dimensional essentials—or mimicked an alphabet in which individual forms are letters to be combined into the vocabulary of fully shaped matter and beings. (In the Timaeus, Plato called his basic triangular form a στοιχεῖον [stoicheion], which can be translated as “letter.”) To extend the metaphor these basic geometric shapes, in providing the foundations of matter, are the letters of what is.

***

For the early abstractionists as for Plato and the early Greek natural philosophers, the world was a κόσμος (cosmos)—an ordered whole that is thoroughly rational and governed by natural regularities. There is an aesthetic aspect to the idea of the cosmos as well, in that the order it embodies is understood to be something beautifully arranged. The geometric form crystallizes this regularity and beauty in its most elementary form.

***

To hypothesize a constant as the stable reality underneath the perceptible world of change is to hypothesize a deeper meaning to the world of change—a meaning that frames change as a relative phenomenon whose real meaning is the stability of the constant undergirding it. In Plato’s universe the triangles that were supposed to underlay the physical cosmos were themselves physical. But in serving as the unobservable constants underneath the observable world of constant change, they carry a metaphysical force by analogy. A similar observation may be made about the geometric foundations of the early abstractionists’ cosmos. For, even if the constant posited as the foundation of the world of change is material, it still implies a metaphysical stance of the primacy of being—of stability—over the dynamic of becoming. In effect, to hypothesize a stable foundation of whatever type is to draw a metaphysical conclusion from assumptions about the physical world, since such a stable foundation would count as that on the basis of which beings are as they are. In effect, the geometric forms of the abstractionists declare a position on the being of beings.

***

The geometrically ordered cosmos represents one attempted solution to the basic metaphysical problem of impermanence. The world and the beings it comprises are, in their givenness to us, seen to be in constant flux, restlessly coming into and going out of existence. The givenness of the world is a play of phenomena in which, as Heraclitus said, πάντα χωρεῖ καὶ οὐδὲν μένει—“everything changes and nothing remains still.” But if we posit geometrical forms as the fundamental elements underlying perceptible change, and that perceptible change is a phenomenon resulting from the combinations and hence transformations made possible by these constant elemental forms, then beings as they appear, change and disappear in their givenness to us represent nothing other than the sensible evidence of the reconfiguration of essentially stable elements. To return to the alphabetical metaphor we may be able to spell out a constantly changing and open-ended vocabulary of words, but the letters that combine to make them stay the same and are part of a finite set.

***

On the one hand the possibility of an underlying constant of geometric forms makes the world of flux intelligible. Geometry is fully intelligible—its elements can be described precisely as mathematical formulas and its basic shapes—lines, curves, angles, and so on—are apprehensible as ideal abstractions transparently present to thought. But in reality it is the world of flux and impermanence—being in its givenness to us as seeming—that makes the possibility of a deeper permanence intelligible. This is because the word of flux is the world as permeated by non-being. In this sense non-being as the pervasive meaning of flux is the repressed double, if we want to think of it that way, of the geometrical forms and their constancy, since it is the possibility of non-being that makes the possibility of permanence thinkable—and not only thinkable, but desirable as well–not the other way around.

***

Again, the possibility that there is a stable foundation to the physical carries overtones of the metaphysical. Having simple, stable and intelligible geometric forms as the foundation of matter dispels a certain unease experienced in the face of flux, and it is this unease that precedes and makes necessary the hypothesis of the simple, stable and intelligible foundation. The existential background to hypothesizing a stable ground of being is the experience of human finitude. Given that background the basic or originary intuition isn’t that permanence or stability is what makes beings what they are—i.e., that permanence is the being of beings—but rather that non-being as their fundamental and limiting possibility is what makes them what they are. That the being of beings is non-being, in other words. That the letters of what is may be written in disappearing ink.

***

If non-being is the true ground being, then beings realize their natural possibility in not-being. Their nothingness is the corollary to their presence, and the fundamental regularity that gives the cosmos its character as a cosmos consists in the tension between the inseparability of being and non-being as mutually implicating possibilities. If so, then matter simply is to the extent that it possibly is not, and is not the extent that it possibly is. Geometry, as well as the abstract art that it inspires, may not directly express this reciprocal relation, but in suggesting a way to make matter intelligible and to put it on a footing of permanence it inevitably takes up a stance toward being that takes us from the purely physical to the perennially metaphysical.

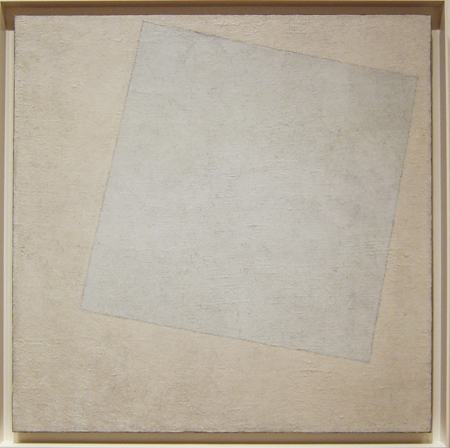

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918

Still, we wouldn’t be wrong to ask if early abstract art did somehow allude to the reciprocality of Being and non-being. Kazimir Malevich’s 1918 Suprematist Composition: White on White is a geometrical abstraction depicting an off-center, tilted white square situated within the larger square white field of the picture plane. The inner square strikingly resembles nothing so much as a sheet of paper from which a text has been scraped off—the painting’s visible brushstrokes evoke the ghostly traces of effaced writing—and which consequently has been prepared to have another text inscribed on it, itself to be scraped off in turn. Read through an understanding of non-being as the ground Being, Malevich’s painting suggests that the letters of what is ultimately reveal themselves to be the text on a palimpsest always wiped clean. (Such an idea, coincidentally, doesn’t seem entirely out of line with Malevich’s own notion of the cycle of reincarnation as constituting a kind of immortality.) This early masterwork of abstraction can, in effect, serve as an iconic simulacrum of the nothingness that is the letters of what is, under erasure.

Read Abstraction and Beyond by Beverly Willis on Arteidolia→

Cloning, Beverly Willis

Cloning, Beverly Willis

◊

Daniel Barbiero is an improvising double bassist who composes graphic scores and writes on music, art and related subjects. He is a regular contributor to Avant Music News and Perfect Sound Forever. His latest releases include Fifteen Miniatures for Prepared Double Bass, Non-places with Cristiano Bocci & their most recent collaboration, Wooden Mirrors.