Interview with Parvathi Nayar

Colette Copeland

February 2024

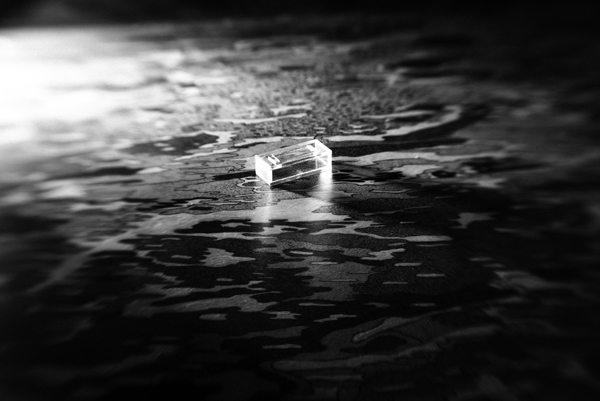

still from Haunted by Waters, 2017

still from Haunted by Waters, 2017

I first learned of Parvathi Nayar’s work from esteemed Delhi curator, arts consultant and writer Sushma Bahl. Although she currently resides in Chennai, Nayar has lived in Singapore, London and Jakarta. I was initially drawn to her large-scale installations and video work, but she seamlessly integrates a variety of media in her artistic practice including drawings, paintings, text and photography. This interview is a result of a zoom chat speaking about art and the challenges of being an artist and single mother in the 21st century.

Colette Copeland: Water is a central theme in your work. We spoke about how living in a coastal region affects one’s relationship to water and the urgency of the water crisis not only in Chennai but globally. Using a variety of cinematic techniques and narrative strategies, your videos explore the pressing issues of regulating the purchase of water, water pollution and water shortages.

In the works Of Space and Time, the beginning segment of Haunted by Waters and part 1 of Water Exchanges, your drawings provide a geographical topography. The surreal black and white footage allowed me to enter into another world, one where I might envision a hopeful future where clean water is plentiful. While Of Space and Time did not directly relate to water, when juxtaposed with the other videos, I interpreted it as a vital call to action. Moments of convergence occur, time stills, and we witness fleeting moments of opportunity for change.

In the beginning of both Haunted by Waters and Water Exchanges, you use stop action animation to depict transformation. I interpreted the brick on water encroachment vignette as human’s interference with the flow of water in the name of industry and development. The channels of reciprocity segment made me consider how humans disregard the idea of mutual exchange. What do we give back to the water, so that it can continue to sustain us. Please discuss your conceptual and aesthetic vision in incorporating drawing and experimental techniques into the video work.

Parvathi Nayar: I really enjoyed our conversation and your thoughtful insights into my work!

Water flows through my work in both visible and subterranean ways. The Brick on Water segment is indeed a comment about illegal constructions on water and land. There’s a term in Tamil called “poromboke” or free land that belongs to the people which includes the rivers and ponds and lakes – that are built over, thanks to human greed … and very often it is such areas that are most susceptible to floods and the torrential rains we experience with climate change.

As a multimedia artist I have a palette of techniques to experiment with, including a core drawing practice. My drawings are very detailed, using stippling as a mark-making process. While there is an obvious homage to pointillism, personally, I trace the lineage to particle physics. The point or punctum is the smallest quanta of matter, whose aggregation creates our known universe.

In this way, the drawings lend themselves well to the creation of heterotopias in my art, especially through their re-photography as stills or video. As you mentioned, I have incorporated elements of my drawings into some of my videos: Water Exchanges, Haunted by Waters, and Of Space and Time. In the latter two videos, the drawn image becomes the setting or the “world” of the action, while in Water Exchanges, the drawings themselves are manipulated to suggest change, transition and flow.

The videos are nearly always within a “guerilla-style” filmmaking in terms of responses to an idea, a sense of immediacy – and certainly budgets! But I believe they carry their own power. I initially filmed using my camera as an extension of the hand-that-draws to capture visual thoughts and notations from the world around me, later converted into a work of video art. While this continues, in a parallel way, some of the videos grew more complex. In order to realize my ideas, certain videos also become collaborative ventures with the editor and cameraman, and sometimes with a musician or a sound artist.

I’ve also done some simple projections of videos on to my drawings at some exhibitions; In To Other Places, for example, an enormous drawing of a stamen covered with pollen “came alive” with the projection of animated drawings of my pollen grains floating away.

still from the installaion WAVE, 2018

still from the installaion WAVE, 2018

CC: Activism and community outreach are key components of your practice. Visually referencing Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai’s famous wood cut The Great Wave, your assemblage sculptural installation entitled The Wave contains salvaged household trash donated by community volunteers. The video By the Mouth of the River culminates with volunteers cleaning up the beach. How does your artistic practice intersect with activism and community engagement? What has been the result of these community projects?

PN: I wanted to work on the three rivers of Chennai in multiple ways. For an Indo-German show called the “Damned Art Project” I decided to recreate a kolam drawing (traditionally done with white rice powder outside doorways as a welcome or invitation) with trash collected from the Adayar River. The result, Invite/Refuse was a trash art installation, that evolved out of a community project. Volunteers collected trash from the Adayar River. Filming the trash collection and clean up over many days also introduced me to life by the river, which is what resulted in By the Mouth of the River.

I wanted to continue this idea of community responsibility and community coming together – which was how WAVE came about. It was an invitation to Chennaites to consciously drop off their blue and white household trash at bins kept at the Alliance Francaise. From this trash I fashioned the WAVE (with a sound component as well). The response to this installation was very powerful among students and the public across many walks of life. It stated without words how we are polluting our waters with plastics that would never degrade, how we are literally drowning in a wave of trash.

The reference to Hokusai’s famous woodcut was of course deliberate. It highlighted these convergences between the power of art, activism and community.

While I interact with activists and community I don’t feel it’s correct to call myself an activist – rather, I use my art to activate some of the issues of our time, especially those around water and waterbodies.

CC: As you know, my Fulbright research centers around themes of borders and boundaries—physical, emotional, real, imagined, geographic, convergent and divergent. I am thinking about how water has shifting or trans-boundaries—flooding during monsoon season, drying up in the heat of summer and how bodies of water serve as a conduit for carrying life force, but also environmental toxins from industry and human negligence. How does your work fit within these themes?

PN: Our waters are carriers of whatever we, in the age of the Anthropocene, choose to put into it – plastics, pollutants, poisons. Waters cross personal boundaries in floods and enter our habitations. Climate change is redrawing our water maps.

Water certainly doesn’t recognize man-made boundaries. This is explored to some extent in the work – in my drawings of river deltas, for example, based on aerial google maps, some which are also featured in the Water Exchanges video.

I’ve also done a series of videos on the tamarind, titled Tamarind Tales, and one video in this set, The Tree that went for a Walk, speaks very specifically about what it means to belong and what it means to be an outsider. The tamarind isn’t native to India, technically, but is so much a part of our culture and life and food.

Recrossing Waters is the title of one of the videos in the video and photography installation Chicken Run for the Chennai Photo Biennale 3. It is based on the Indian experience in Korea in 1953/54, when 6,000 Indian soldiers crossed the seas from Chennai to go to the Korean DMZ. They went to help bring peace and sort out the Prisoner of War issue that threatened to derail the signing the Armistice that ended the Korean War. My father was among the soldiers in the DMZ, a singularly contested boundary, and his videos shot at the time are part of the Chicken Run project.

A series of drawings for this project (that also draws abstract parallels between the migrations of humans and birds) looks at the shrinking boundaries of Chennai’s Pallikaranai wetlands over the years.

My work with water extends to the fauna and flora associated with it. Plants and animals need water for sustenance, of course, but are also entangled with water in terms of habitats and life cycles. With birds, especially, migration patterns know wetlands and marshes, not political boundaries and countries.

CC: You are one of the founders of the arts initiative The Hashtag#Collective. How did that come about and what are some of the projects realized by the group? Where can we see the work?

PN: Currently, the Hashtag#Collective consists of two artists (Saira Biju and myself) and two architects (Biju Kuriakose and Abin Chaudhury). We also work with people from different disciplines for different projects – including fishermen for the temporary site-specific installation titled Transitional Boundaries using fishing nets.

The four of us came together to form the Collective as a way of exploring socio-cultural issues as well as spatial and material ideas, as an extension of our respective practices. We’ve done installations on the changing environment of Kochi (Reflecting (on) the Inhabited Crossroads), on the contemporary question of identity in GenderFluid, and on the role of Women in South Indian Cinema in the show Of Desire and Disappearance.

Working within the Collective’s space offers each of us opportunities to bounce ideas off each other. Though we only come together for a few selected projects, and our enquiries are related to that specific project, such learnings also inform our individual works.

CC: What are you most excited about in your artistic practice right now?

PN: I am deeply excited by my multi-pronged works about water. These are in the form of several long-running, complex projects that I hope will see completion soon. Ongoing through all this is the studio work, the drawings and multimedia paintings.

Among the water-related work is a video project on a fisherman who has been collecting daily on-the-ground data for over four years about the conditions of the seas adjoining his fishing village – it is something that I’m very excited about.

I’m also curating an exhibition that is very challenging and of-the-moment, on climate change and our waters, titled The Living Ocean for the Dakshinachitra Museum. It is deeply meaningful to me to bring together the diverse strands of this thematic show.

I’m also continuing to work with my niece Nayantara Nayar on an Indo-Korean project called Limits of Change; the work Chicken Run that I mentioned earlier is part of this.

I think my works with water bring me nearer the community and the place of Chennai. This makes the work feel meaningful, as part of the environment, histories and lives of the people here.

Parvathi Nayar’s short story “Body of Research” on usawa→

Parvathi Nayer / website →

Instagram →

As part of her Fulbright Research Award in India, Colette Copeland has been doing a series of interviews with socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Manmeet Devgun →

Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty →

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.